Last week, CapX published an essay from Karl Williams throwing the fiscal challenges posed by Britain’s ageing population into sharp relief. To recap: the Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts that over the next 50 years, public spending on the over-65s will rise from 10.1% of GDP to 21.3% of GDP, driven by the rising cost of the state pension and pension benefits, adult social care, and healthcare for the elderly. In present-day terms, that 11.2 percentage point increase in the share of GDP devoted by the state to the elderly equates to approximately £285bn. That is the fiscal black hole that, all else being equal, policymakers will have to attempt to fill over the next five decades. And that, as Williams notes, is based on the elderly not using their predominant power at the ballot box to vote themselves more goodies at the expense of the young.

So what are our options? Many on the left would say that the answer is simple: taxes have to rise. Britain, they argue, is a relatively low-tax country. There is plenty of scope to move us up towards the European average, for example by targeting higher earners and corporate and investment income.

In fact, as this essay will show, the scale of the challenge is such that only extremely onerous, broad-based tax rises will suffice. To say that such tax increases would be politically unappealing is to put it very mildly indeed.

The best way out of the tax and spend vortex, as Williams said, is economic growth. But as he also made clear, it would require an extraordinary acceleration of growth, in the face of substantial demographic headwinds, for us to maintain living standards for the young and the existing panoply of benefits for the old.

So as the concluding section of this essay will argue, the only real solution is a full-spectrum approach: a renewed focus on economic growth, radical reform of age-related public expenditure and services, and policies that might support a higher birth rate.

It is always possible, of course, that some extraordinary technological breakthrough will come along to save us. But it would be unwise to sit around waiting for the singularity – which means that Britain’s policy establishment needs to face the facts and start now on the changes necessary to avert disaster down the line. Without sustainably stronger economic growth, more children, and a reformed welfare state that stresses personal responsibility, we risk sleep-walking into a fiscal calamity – with today’s young people left to shoulder the very heavy burden it will impose.

It is often said that Britain is a relatively low-tax country. But measured by our own historical standards, this is not the case – and even by international standards, it is becoming rapidly less so as we speak.

As the Office for Budget Responsibility put it in its most recent Economic and Fiscal Outlook, the tax burden will rise to 37.7% of GDP in 2027-28, which is not only a postwar high but a full 4.7 percentage points above where it stood before the pandemic. It is no surprise, then, that many Britons are feeling the pinch – especially when one of the main drivers is frozen tax thresholds during a period of high inflation. (We are talking here about tax revenue rather than government revenues as a whole, which are slightly higher.)

It is also unsurprising that Conservatives increasingly despair about the fiscal legacy of their current stint in government. The last time they spent 14 years in power, they managed to get taxes down to a post-war low (in 1993) of 27.4% of GDP. Were that the case today, the Chancellor would be in a position to announce a quarter of a trillion pounds worth of pre-election tax cuts at next year’s Budget – almost enough to scrap income tax altogether.

The reality, of course, is very different: even if headroom is found for a few targeted giveaways, they will likely be no more than a temporary reprieve. Overall, the tax take is heading inexorably upwards. Projections by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) have total expenditure approaching 55% of GDP in the 2070s – driven by the trends identified by Williams in his essay. Unless we are going to run the mother of all deficits, decade after decade, taxes will have to rise to match.

To which some might say, so what? After all, the tax take might be high by British standards, but many other countries raise more than we do as a percentage of GDP. Aren’t we just seeing the inevitable end of our attempt to run a European welfare state with American taxation?

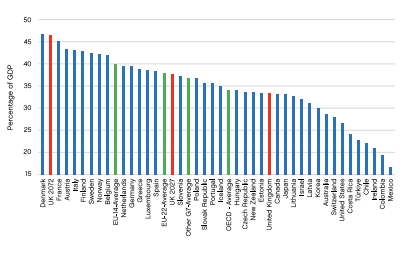

There is some truth to this narrative. As the chart below shows, the UK is a relatively low-tax country by international standards – at least based on the latest comparable data, which is from 2021. At 33.5% of GDP (according to OECD figures), the UK’s tax take puts it in the bottom half of the table among advanced economies. Our tax take in 2021 was fractionally below the OECD average and further below the average for other G7 countries (36.9%), the EU-22 (37.9%), and the EU-14 (39.9%).

Source: OECD Global Revenue Statistics Database, OBR.

Source: OECD Global Revenue Statistics Database, OBR. However, there are a few countervailing points to make here. First, all else being equal, the UK’s tax take will have leapfrogged the OECD average and the average for other G7 countries come 2027 – by which point it will be roughly equivalent to the average for the EU-22.

Second, raising taxes enough to fund the 2072 welfare state doesn’t just mean converging with the European average – it would mean jumping all the way to the top of the table and more or less equalling the tax take of today’s highest-taxing advanced economy, Denmark. But that in turn assumes that we can still borrow our way out of trouble: in the figures we are extrapolating from, the deficit stood at more than 5% of GDP. The OBR has argued that borrowing will become more expensive in the coming decades, meaning that we will either have to narrow the deficit or increase the amount of GDP devoted to repaying our debts.

Of course, there is a certain artificiality to these comparisons. Almost all developed countries face the same sort of demographic pressures as we do, so their tax takes are unlikely to remain static over the next five decades as the UK’s grows. But the chart above does serve to illustrate an important point: in today’s terms, paying for an ageing population doesn’t mean the UK going from ‘relatively low tax’ to ‘average tax’ – it means becoming what most of us would see as a very high tax and big state economy.

It is also worth pointing out that there are probably limits as to how far taxes can rise before they start to significantly weigh on a country’s economic dynamism. Without policy change, therefore, paying for an ageing population is likely to mean different countries’ tax revenues converging at a high level, rather than rising proportionally and in lock step across advanced economies.

Taxed enough already?

Of course, it is one thing to look at macro-statistics like total tax revenue as a percentage of GDP and draw conclusions about how high or low tax a particular country is. But those conclusions will not always map neatly on to how ordinary workers and families experience the tax system. For example, recent CPS research highlighted how a married couple with two children and a single earner on the average wage face a higher average tax rate in Britain than they would in France or Germany, which both look like much higher-tax countries if you simply look at the total tax take.4 (For single taxpayers with no children, the situation was reversed.)

Then there is the question of effective marginal tax rates. In some cases, it might be that a particular taxpayer does not face an especially high tax burden overall, but that they do face a high tax burden on the next pound they earn. This matters a great deal for economic incentives, and can determine whether it pays to work, or to work more. Even at relatively modest incomes, effective marginal tax rates in the UK can be onerous, or even punitive.

For example, someone earning the minimum wage for a full-time job might be subject to income tax, National Insurance, and the Universal Credit taper, and therefore face an effective marginal tax rate of 69.5%. A working parent with three children will face an effective marginal tax rate of 73% if their income goes above £50,000, and they are subject to the child benefit tax charge, income tax, and National Insurance simultaneously.

You do not need to seek out special cases, or circumstances where the tax and benefits systems uncomfortably overlap, to identify effective marginal tax rates that are really rather high. Picture a youngish graduate earning an average wage (for the sake of argument, let’s say £35,000). They would be a basic rate income taxpayer (20%). They would also face the standard rate of National Insurance (12%). If they are making student loan repayments, that adds 9%. Auto-enrolment pension contributions take another 5%. Put that together, and you’ve got a marginal tax rate of 46%. For every additional pound that this taxpayer earns, they will only see 54p of it in their take-home pay.

Now, you could object to this analysis in two ways. First, you might say that it is wrong to include student loan repayments and auto-enrolment pension contributions because these are linked to benefits that the taxpayer has enjoyed in the past (a university education) or will enjoy in the future (a more comfortable retirement). And this is largely a fair criticism. But it does not affect the fact that these taxpayers, who will be expected to cough up a lot more to pay for an ageing population in decades hence, already see relatively little of any extra money they earn.

Second, you might object in the other direction, and say that we are ignoring employer-side costs that ultimately reduce wages. For example, economists generally think that most of the incidence of a payroll tax like employers’ ***** National Insurance falls on employees, in the form of lower wages, even if the company technically pays it. The same is likely true of mandatory retirement contributions, like the 3% auto-enrolment pension contributions that British employers must make unless their employees opt out.

Factor these into the effective marginal tax rate faced by our average earning, youngish graduate, and you come out with 54% – meaning that for every extra pound they cost their employer, they will see less than half of their take home pay. Ask this taxpayer to foot the bill for an ageing population, and they might legitimately say, ‘Aren’t I taxed enough already?’

Indeed, the political power of the grey vote, identified by Williams, has ensured that these workers have already borne a disproportionate share of recent tax rises, for example via the freezing of income tax thresholds and allowances such as the Help to Buy ISA, even as elderly benefits have been protected against inflation. (The emblematic example of this was the proposal to increase National Insurance to fund elderly care – a tax, symbolically, not paid by the elderly themselves.)

The impact of raising taxes to pay for an ageing population

The standard left-wing response to the above would be to say that there is no need for such taxpayers to continue to take the strain. Instead, we can get the money we need from the rich, from corporations, and from ‘unearned’ investment income. But can we really?

The Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts us to be spending an extra 11% of GDP – about £285bn in today’s terms – on pensions, social care, and healthcare for the over-65s in 2072.

For better or worse, it is difficult to see a standard left-wing tax package filling that gap.

Let’s start with Jeremy Corbyn’s 2019 plan for the income tax system. If he had become prime minister, he would have added a new 45p tax band at £80,000, and taxed incomes beyond the point at which withdrawal of the personal allowance ends (£125,140 today) at 50p. If you put those tax changes into PolicyEngine, you get a budgetary impact of +£4bn.

Various other suggestions can be taken from the IPPR, who have suggested aligning capital gains tax rates with those for income tax (+£12bn), extending National Insurance to investment income and pensioners (+£12bn), replacing inheritance tax with a lifetime gifts tax (+£9bn), and abolishing non-dom status (+£3bn). You might also raise corporation tax to 30% (+£15bn) while getting rid of various capital gains tax reliefs for investors and tax exemptions for private schools (perhaps another +£5bn collectively).

Such an agenda would, rightly, be seen as a massive tax hike. But it would still only raise around £60bn a year – just over one-fifth of the way to the target. In doing so, it would also have a pronounced effect on economic growth. Corporate income taxes are the type of tax most strongly associated with a negative effect on GDP per capita. (The evidence also suggests that their main effect is to reduce wages.) Significantly raising taxes on investment, meanwhile, is akin to eating seed-corn – it is effectively a tax on future prosperity, and may therefore be self-defeating in the long run. Once you account for behavioural effects, the promised revenues may never arrive. Another left-wing idea – a one-off wealth tax – might deliver bumper revenues once, but is no way to fund a welfare state on an ongoing basis. It is also likely to have a distinctly chilling effect on future wealth creation.

In short, if you have to raise the sort of money we’re talking about here, there is no way to avoid broad-based tax increases on ordinary families’ earnings and spending. Based on PolicyEngine modelling, one way to fill the £285bn black hole (Scenario 1) would be to put 10p on the reduced and standard rates of VAT (raising them to 15% and 30%, respectively) while also adding 28p to each income tax band – thus increasing the basic rate to 48%, the higher rate to 68%, and the additional rate to 73%. In principle, at least, such a scheme would raise the necessary funds. But it would also increase poverty by 57.8%, and cost the average household nearly £8,000 per year.

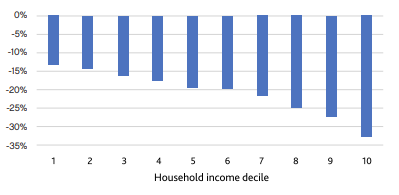

Relative impact on net household income by decile under Scenario 1

Source: PolicyEngine modelling

Source: PolicyEngine modelling Of course, it is highly questionable whether this tax package would actually deliver as much revenue as a static analysis would suggest. Top tax rates of 45p or 50p may or may not be the wrong side of the Laffer Curve (the point at which tax rates so discourage economic activity that they lose revenue rather than raise it) but rates of 68p and 73p almost certainly are, especially with National Insurance on top.

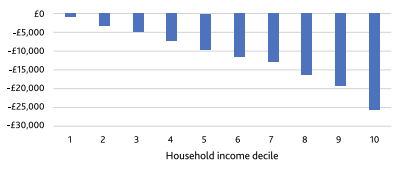

A second scenario, which economists might judge more likely to succeed in raising revenue (at least in a world without politics), could involve the following policies: raising the standard and reduced rates of VAT to 25p; replacing council tax and stamp duty land tax with a 2% residential land value tax; scrapping employee National Insurance and charging income tax at a flat 50% on all earnings; and paying all adults a £50 per week ‘basic income’ (as a partial replacement for various tax allowances). The downsides would be a near-tripling of poverty among seniors and a reduction in net household income of nearly a quarter.

Absolute impact on net household income by decile under Scenario 2

Source: PolicyEngine modelling

Source: PolicyEngine modelling Needless to say, the point of these examples is not to suggest what should be done to the tax system over the course of the next 50 years, but rather to highlight how unpalatable future fiscal policies are likely to be if we do not do everything in our power to get a grip of age-related spending and boost economic growth now.

The examples presented here might be extreme, and of course there are all sorts of ways a government might seek to raise revenue that cannot be straightforwardly modelled using an open source system like PolicyEngine. But whichever way you slice it, one inescapable fact remains: unless we get our act together soon, today’s children are going to be forced to shoulder an extremely high tax burden over the course of their working lives. If we care about justice for the young, that is an outcome we should be bending over backwards to avoid.

Is there another way?

It is easy to look at the fiscal projections outlined by Williams and be filled with despair. It is equally easy for that despair to translate into inertia. If a problem looks so large as to be unsolvable, then why would any politician risk the massive political hit that starting to deal with it might involve?

And that, roughly, is the story so far. The potential fiscal impact of Britain’s ageing population is not exactly news – people have been talking about it and writing about it for years, if not decades. But far from tackling the problem, we have been busy making it worse, with policies that undermine economic growth and increase fiscal commitments to the elderly. Westminster’s wilful blindness to these issues – despite biennial reports from the OBR laying them out in gory detail – is the epitome of political short-termism and rank irresponsibility.

Change is long overdue. But what form should that change take? Ultimately, we need bold, decisive action on three fronts – growth, families, and the welfare state. And we need the focus on reform to be sustained over a long period of time. Future-proofing the British economy is not the work of a single Budget or election manifesto: it will need an all-encompassing programme of reform for many years to come.

The precise policies involved could be the subject of countless essays, each much longer than this one. In what follows, I will simply outline the main areas that are in need of attention.

First, economic growth must genuinely be made central to everything the government does. Plenty of politicians have paid lip service to this idea, of course. But few seem to have grasped what it would mean in practice. A regulatory system designed to maximise growth would look nothing like the one we have today. Interventions would be light-touch and few and far between, focusing solely on cases where clearly defined market failures give rise to significant and likely harms.

A tax system designed to maximise growth would not aim to redistribute income, but rather to raise funds in the least distortionary way possible. Such a system would consist mostly of a broad-based VAT, a land value tax, and a flat tax on personal and business income that gave full relief for saving and investment.

Above all, putting growth first would mean the near-complete liberalisation of land use planning, so that the market could deliver housing, commercial development, infrastructure, and cheap, abundant energy according to demand.

Second, we should not accept that our demographic decline is inevitable. Whether to have children and how many to have should always be a personal decision, but it is nevertheless clear that people generally have fewer children than they say they want, and that supportive policies can make more and larger families possible.

Deregulating land use is crucial here, too, so that we can build plenty of family homes where parents and their children want to live. Liberalising childcare – getting rid of barriers to entry and regulations that raise costs – would help. We might also want to look at generous family tax allowances, like those in France and other countries, to ease the financial burden of child-rearing for working parents. Reversing demographic decline also means taking on doom-laden visions of the future that discourage some young people from starting families.

Third, we need to start reforming our welfare state with an eye to the future. That means trying to downsize demands on the state (and by extension the taxpayer) while boosting the role of personal responsibility. This would require significant long-term changes to pensions, social care, and the NHS – and is obviously a very challenging agenda from a political perspective.

On pensions, the goal must be to gradually reduce the value of the state pension while also boosting private savings for retirement – so that future retirees depend more on their own nest eggs, and less on future taxpayers. Of course, as Williams notes, the triple lock pushes in the opposite direction. And while auto-enrolment has been a huge success in getting more people to save, they generally aren’t saving enough, and there remain gaps in provision.

Nevertheless, with a clear long term strategy, the balance could gradually be shifted, delivering savings over the long run without exposing pensioners to any hardship. The long-term goal should be to get as close as possible to a fully pre-funded pension system – that is, one in which benefits are paid out of past investments, rather than funded by the contributions of current workers.

On social care, we must resist the temptation to make care for the elderly the general responsibility of the taxpayer – whether by fully funding private provision or, worse yet, nationalising it as part of the NHS. There will be strong arguments in the other direction. But from a fiscal standpoint, we are already in a hole and we should avoid making it deeper.

The big challenge here is to make some form of insurance financially viable. Some have suggested that government could foster an affordable private market by taking on the ‘tail risk’ of insured people needing care for a very prolonged period. Lord Lilley, a former Secretary of State for Social Security, has outlined a way those approaching state pension age could pay a one-off care insurance premium via a modest charge on their home (which would be recouped later, once the house was inherited or sold). Damian Green, another former Secretary of State, made similar proposals in a paper for the CPS. All share the position that individuals need to contribute more towards their own care, and that this can be done via the creation of an insurance market, without forcing them to sell their own homes.

Finally, healthcare is both the most important thing to fix and the hardest, practically and politically. Part of the problem is that innovation in healthcare, which is of course welcome, often makes care more expensive overall, by expanding the range of treatments and technologies available. It is possible that some coming innovations will work the other way – such as anti-obesity drugs making chronic illnesses less common among the elderly – but we should not count on technology to make the books balance.

Ultimately, we need structural changes that improve the economics of healthcare in an ageing society.

Obviously, every discussion of the NHS starts from the premise that healthcare must be free at the point of use. Yet this not only puts an ever increasing burden on the taxpayer – including those of working age – but insulates patients from the financial consequences of their decisions. The result is either to inflate demand, or to impose de facto rationing via scarcity – precisely what we have seen in the health service in recent years, despite the record sums being spent. And to make matters worse, ours is not merely an ageing society but an increasingly overweight one: almost three quarters of people aged 45-74 are now overweight or obese. It may be that Ozempic and other semaglutides can turn the tide. But if not, there will be a bow wave of costs from unhealthy lifestyles.

There are obviously many policy changes that could help bend the cost curve downwards. The need to shift the balance of treatment more towards prevention than cure is something that has been talked about for decades, but is no less true: it is cheaper to fit a handrail than to fix a hip, not to mention greatly to the patient’s benefit. However, that kind of shift will not only demand more money in the short term, but also involve pulling power away from hospitals, which has historically been an extremely difficult thing to make stick. It is also worth pointing out that while it would be good for both patients and the economy to extend healthy life expectancy, we will still confront the problem that an ever more elderly population develops ever more comorbidities at the end of life – complex conditions that are correspondingly expensive to treat.

If we are genuinely to keep the NHS affordable, we may need to tackle that most sacred cow of all, and ask those who can afford it to contribute directly to their own care. If you were setting up a health system now, you would almost certainly adopt some element of ‘pre-funding’ – that is, building up funds over people’s working lives that can be drawn down in their old age. Transitioning to such a system now might be tough, but not impossible. We already use personal budgets on a small scale in health and social care, but a system such as Singapore’s MediSave accounts would allow most people to accumulate savings to pay for basic healthcare directly, without taxpayer involvement and the inefficiencies that third-party payment entails. They would also introduce a degree of de facto pre-funding into healthcare for the (future) elderly – much to the benefit of the following generations.

More widespread deployment of user fees and co-payments within the health system would help keep healthcare demand under control. It would also shift some of the burden of financing healthcare from (typically younger) general taxpayers to (often older) service users. We could also extend the role of market pricing and competition. Assuming that the taxpayer continued to have a primary role in funding healthcare, this would mean putting money in the hands of patients, wherever possible, and letting them choose between different providers who would compete transparently on price (and a range of other factors).

None of this will be popular, or uncontroversial. None of it will happen overnight. But over a half-century horizon, it will be grotesquely unfair to the young to ask them to bear the inflated health and care costs of the richest cohort in history, rather than asking that cohort to contribute directly for their own care.

Conclusion

The welfare state, as it exists today, is not sustainable in the context of an ageing population. Over the next few decades, a rising tide of spending on the elderly risks overwhelming anything else we might want to do for the younger generation, by burdening them with rapidly rising tax bills (without any commensurate increase or improvement in the services they receive).

The idea that the fiscal costs of an ageing population can be funded by targeted taxes on politically soft targets – big corporations and the wealthy – is a fantasy; without policy change, tax increases will have to be broad-based and very significant indeed. Ordinary families rightly feel that they are taxed enough already, but sadly, if the OBR’s projections come to pass, they ain’t seen nothing yet.

At some point, policymakers will surely have to face up to what is coming down the track and attempt to change course. That process is never going to be easy, but the longer we leave it, the harder it will get. Radical reform of pensions, social care, and the health service is essential. But we should not just focus on the public spending side of things. An all-encompassing programme of economic liberalisation could, if it succeeded in raising the growth rate, make the burdens of an ageing population much easier to bear. Similarly, if we can help people to have more children today, tomorrow’s old-age dependency ratio will start to look a lot more manageable.

It is wrong, though, to frame these sorts of reforms purely in fiscal terms. After all, if our goal is to deliver a brighter future for Britain’s young, what could be better than giving them a more dynamic economy, with all the opportunities that entails, as well as the chance to raise in comfort whatever size of family they desire? That really would be justice.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.