Capital Gains Tax (CGT) was introduced to Britain in 1965 by Harold Wilson’s super-high taxing government – the one about which The Beatles wrote their protest song The Taxman: “Should five per cent appear too small? Be thankful I don’t take it all.”

Now the idea of increasing CGT, far beyond what the Fab Four lamented, and even to as high as income tax levels, is being floated as means of raising revenue to pay back Covid borrowing. In practice such rate increases are more likely to result in lower revenues. Cutting rates would be a better approach, as numerous international examples show. For example when the CGT rate in Ireland was cut from 40% to 20% the yield more than doubled.

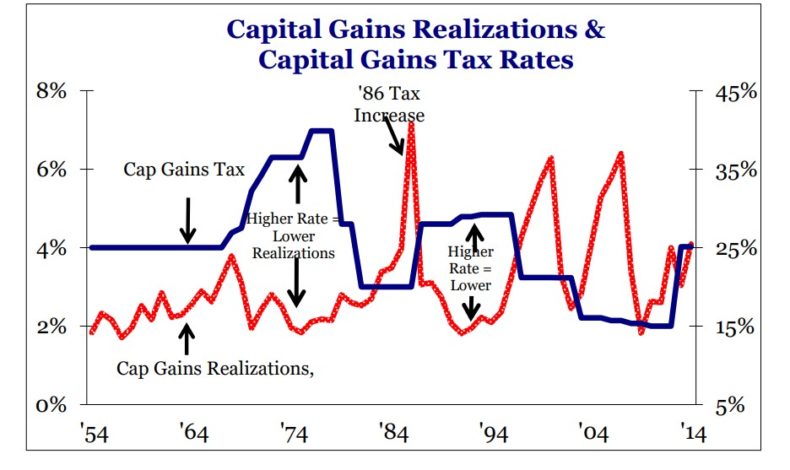

The graph below showing realisations of capital gains versus tax rates in the USA from 1954 to 2014 demonstrates clearly that when tax rates are high, investors realise fewer gains. Conversely, when tax rates are lowered, investors realise their gains.

.

.

The Laffer effect with regard to income taxes is well known. When income taxes go above a certain level, revenues fall as the incentive to work decreases. But with capital gains taxes the effect of tax rises is much stronger and more immediate.

The main reason for this is clear. Unlike income taxes, capital gains taxes are voluntary. While everyone needs to work and bring in an income, the same is not true of making capital gains. No one needs to sell assets and pay capital gains taxes unless they are in financial distress. Taxpayers can simply avoid selling assets that are subject to the tax and also avoid buying such assets.

This leads directly to the ‘lock-in’ effect, where taxpayers delay or avoid selling assets in order to avoid the tax hit. After the economic dislocation caused by Covid we need investment resources to flow quickly to where they are most needed, rather than pressuring people to hold on to them to avoid a punitive tax rate. Economic growth is dependent on capital moving from older to newer, more efficient uses. Capital gains lock-in thus has a significantly negative effect on market efficiency, growth and living standards.

Wages rise primarily because of increases in productivity – the reason why a worker in 1996 had to work only 10 minutes to earn what his or her 1900 counterpart took an hour to earn. Capital makes possible this productivity increase and when it is taxed more, less is invested. The OECD, in a study of tax policy of its member countries, found that concern over lock-in and its damaging effects on growth was one of the main reasons that tax officials had favoured reducing taxes on capital gains.

There is an old argument that lower capital gains tax rates somehow result in people shifting income to capital gains, but the facts do not bear this out. If it was so easy to convert income to capital gains then how do countries who have a CGT rate of zero still manage to raise significant revenue from income taxes? In fact international evidence suggests that the switching problem is an imaginary one and any attempts at income-switching can be dealt with by anti-avoidance measures.

In the case of Hong Kong, for example, Professor Berry F.C. Hsu and Chi-Wa Yuen undertook a detailed study into the extent of tax avoidance due to the zero capital gains tax and stated that: “On the basis of the indirect evidence available to us we conclude that the absence of a capital gains tax in Hong Kong has resulted in little, if any, inefficiencies and inequities.”

Britain’s need to compete internationally is, of course, a critical reason why increasing capital taxes would be a profound act of self-harm. After Brexit we need to attract capital, investors and entrepreneurs. To say to them ‘come to Britain, we’ve just increased capital taxes,’ would seem an extraordinarily foolish move. After all we are already competing with countries that don’t levy CGT on individuals, such as the Netherlands, Belgium, Singapore and Hong Kong, as well as many other European countries with much lower rates than Britain. Take the US, where the rate is 20% – are we going to attract US investment if our CGT rates are over twice as high? Capital today is highly mobile across borders. We need more of it, not less.

That is why the misnamed Office for Tax Simplification’s suggestion that capital gains tax rates should be increased to income tax levels can most politely be called economically illiterate. What will they come up with next? Perhaps just a two line tax return – “How much money did you make this year? Send it to the Government now.”

Boris Johnson’s government should now reduce CGT rates and announce its intention to abolish them outright in the longer term. This would be a clear sign that Britain had really thrown off its high tax history and committed to a strategy based on attracting capital to achieve the growth we so badly need.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.