In recent years, income inequality has become a major political and economic issue in America. Income inequality, the argument goes, was caused not only by the growth of incomes among the wealthy, but also by wage stagnation among middle-class Americans. According to a 2015 report issued by the Economic Policy Institute, a pro-labour think tank based in Washington, DC, “ever since 1979, the vast majority of American workers have seen their hourly wages stagnate or decline”.

The blame, predictably, fell on President Ronald Reagan and his free-market reforms, even though economic liberalisation started under his Democratic predecessor, Jimmy Carter. But, income is an imperfect measure of overall living standards, which are much better than they used to be.

It is true that, adjusted for inflation, average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees in the private sector (the closest approximation for the quintessential blue-collar worker that I could find) have barely changed between 1979 and 2015. In October 1979, average hourly earnings stood at $6.51, or $21.20 in 2015 dollars. In October 2015, average hourly earnings stood at $21.18 – slightly below the inflation-adjusted 1979 level. But wages do not provide the full picture of workers’ earnings.

In recent decades, for example, non-wage benefits have exploded. Today they include relocation assistance, medical and prescription coverage, vision and dental coverage, health and dependent care, flexible spending accounts, retirement benefit plans, group-term life and long-term care insurance plans, legal and adoption assistance plans, childcare and transportation benefits, paid vacation and sick leave, and employee discount programs from a variety of vendors, etc. These could amount to between 30 and 40 per cent of the workers’ earnings.

Moreover, prices of many important consumer goods have declined dramatically. Comparing the prices of everyday items in the 1979 Sears Catalogue with similar products on Walmart.com at the end of 2015, I found that the inflation-adjusted prices of bicycles, blenders, coffee makers, convection ovens, dishwashers, food processors, refrigerators, gas grills, home entertainment systems, gas stoves, microwaves, slow cookers, toasters, treadmills, television sets and vacuum cleaners fell by an average of 76 per cent.

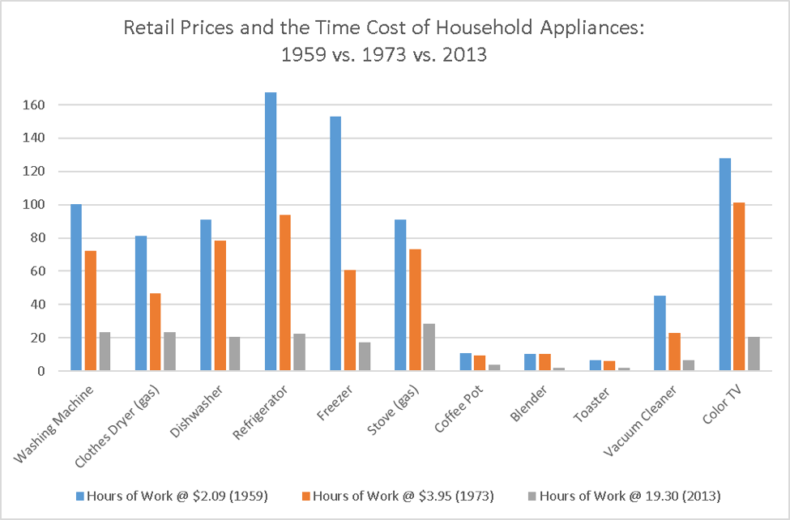

This is not a fluke. Writing in 2015, Professor Steven Horwitz of St. Lawrence University found a similar trend. According to Horwitz, whose data I represent in graph form below, retail prices of common household appliances fell by 81 per cent between 1959 and 2013 in terms of hours of labour needed to purchase those items.

More recently, Bruce Sacerdote from the Department of Economics at Dartmouth College found that “the pessimistic narrative on real wages is somewhat at odds with casual empiricism about material goods consumption”, and that “consumption for below median income families has seen steady progress since 1960”.

According to Sacerdote, house size inhabited by families below the 50th percentile increased from 1,200 square feet to 1,300 square feet between 1993 and 2009 alone. The number of bathrooms rose by 50 per cent between 1986 and 2015. Families below the 25th percentile owned 0.75 cars in 1970, but 1.4 cars in 2015. In 1960, 35 per cent of those families enjoyed no indoor plumbing. By 2015, virtually all had it. Both groups saw the number of bedrooms per family increase by 10 per cent since 1960. All the above improvements happened, while the average size of the American family declined.

Why is there such a disparity between the reality and perception? Sacerdote claims that improvements in standards of living are underestimated because of “new goods bias” or failure to quickly account for the spread of new goods; “product quality bias” or failure to account for growth in product and service quality; “outlet bias” or failure to incorporate availability of new less expensive outlets such as Walmart; and “substitution bias” or failure to account for consumers’ ability to substitute away from goods and services that have become relatively more expensive.

However, Sacerdote also found some demographic sub-groups, such as less than high school-educated men, might have actually become poorer over the last half-century and noted that many Americans can nevertheless feel poorer, due to more information about the living standards of other Americans.

Social dysfunction among less than high school-educated Americans, misinformation and, unfortunately, envy, contribute toward underestimation of gains that Americans have made in recent decades. Thankfully, none of that diminishes the real progress that ordinary Americans have made thanks to free trade and free markets.