In a surprise move, the Bank of England has voted 5-4 to hold rates at 5.25%. Many financial market participants and monetary policy Kremlinologists had expected a rise to 5.5% but it was acknowledged as a knife-edge decision.

There is a three-way split in current UK monetary policy thinking. The first camp (not represented on the Monetary Policy Committee but with significant media presence) we might call the ‘monetarists’ – those who place significant weight upon monetary data in guiding their thinking about monetary policy. Having urged higher interest rates for much of the past decade and warned early about the inflationary consequences of the large amount of QE done late in the Covid period (especially in 2021), this camp has recently swung to the other end of the spectrum.

Some monetarists (including yours truly) were urging that interest rate rises be paused as long ago as the spring, when rates were still at 4%. It wasn’t necessarily that we were urging that 4% be the peak. We might eventually have wanted rates to rise to similar levels to now, just after a pause to check what the impacts would be of the already-rapid rises that had occurred by then. We can boil this thought down to two key factors.

First, monetary policy operates with a lag. For example, raised interest rates will continue to feed through to higher mortgage rates for a year or two even after interest rates peak, because people on fixed rate mortgages will only experience the rise when their fixed rate term expires.

Second, for some considerable time now it has been clear that monetary growth had slowed markedly, and now it is in outright contraction.

‘.

UK M4ex Broad Money Growth (Source: Bank of England)

The relationship between monetary growth and inflation is not precise or mechanical and does not arise with reliable lags, but broadly speaking if money growth is very rapid (eg the 15% levels we saw in 2021) one can expect rapid inflation perhaps 18 months or so later. And if monetary growth is negative (as it is now), and especially if it becomes markedly negative (as current trends suggest it might) then inflation can be expected to be very low or even negative around 18 months later, even without additional tightening.

So much for the monetarists. The next school we might term the ‘hawks’. These urge that raising rates too far is better than risking raising them not far enough, because of the risk inflation expectations rise and inflationary tendencies become embedded in firms’ decision-making and in wage-setting. The highest-profile area of such concern has been wages.

‘

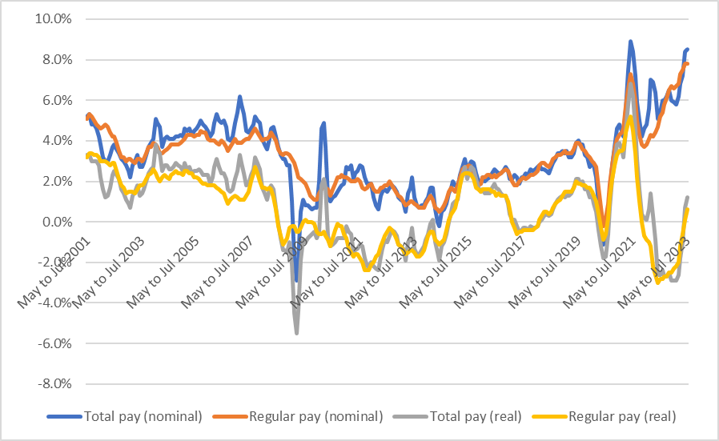

UK Annual Pay Growth

Recent regular pay growth has been at its most rapid this century. Those who believe in ‘wage-price spirals’ are concerned that rapid pay growth will force up firms’ costs so firms raise prices to remain profitable, so inflation becomes persistent and workers continue to demand rapid wage increases.

Those disputing this story reject the concept of a ‘wage-price spiral’ as bad theory and emphasize that in real terms wage growth is still low even by the standards of most of the past decade. Workers have merely been catching up some of the rapid real-terms reductions in wages they experienced, because of high inflation, until only a few months ago.

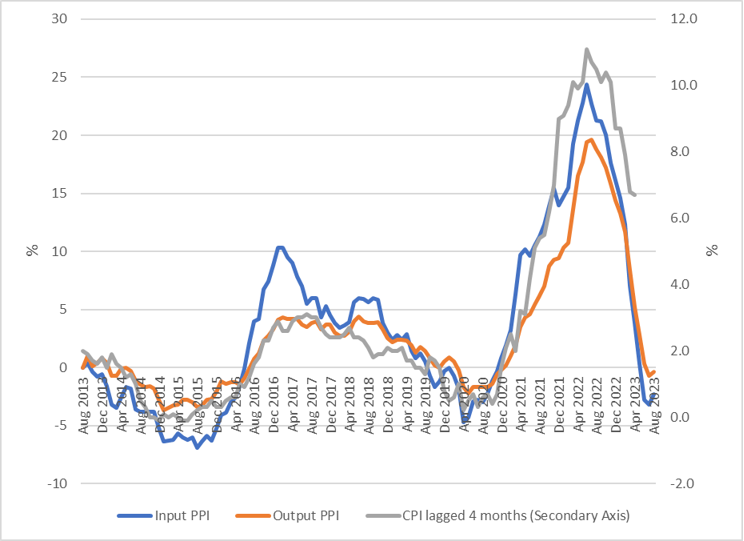

The third camp are the ‘Goldilocksers’. These reject both the ‘too much’ story of the monetarists and the ‘too little’ story of the hawks, and think the current set of rises is just right, with no more needed for now. They point to fairly resilient (albeit not spectacular) GDP growth data showing growth in the most recent three months as demonstrating that the fears of monetary overkill have thus far proved unfounded. And they say that the forward indicators suggest that inflation will fall quite rapidly now rather than become persistent. For example, producer prices inflation tends to run about four months ahead of consumer prices inflation, and has fallen sharply in the past few months.

‘

Comparison of producer price inflation with CPI inflation four months later

The Goldilocksers carried the day. So we can expect 5.25% to have been the peak unless something unexpected causes inflation to rise again. Then we shall have to wait to see, over the next year or two, how accurate the concerns of the monetarists prove to have been, and whether those that choose to ignore monetary data will start cutting rates too late as inflation falls just as, by ignoring that data a couple of years ago, they started raising rates too late as inflation rose.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.