This piece was originally published on the Centre for Policy Studies’ monthly newsletter, which you can sign up to here.

If there’s one clear economic lesson we should take from the last 20 years, it’s that where markets are allowed to work, we get richer, and where they were restricted, we get poorer.

In terms of earnings, the average British worker is hardly any better off than they were in 2008. While anaemic GDP growth has been sustained by an expanding workforce, national income per person has barely risen over the last 15 years. If growth had resumed in line with the trend over the preceding 50 years, the average worker would now be about 30% better off in real terms – that’s over £200 per week in today’s money.

The causes of this growth slowdown are complex and much debated. But for now, let’s look at the other side of the equation. For of course, weak wage growth would matter a bit less if the goods and services people want to consume had become more affordable in real terms. And the picture here is decidedly mixed.

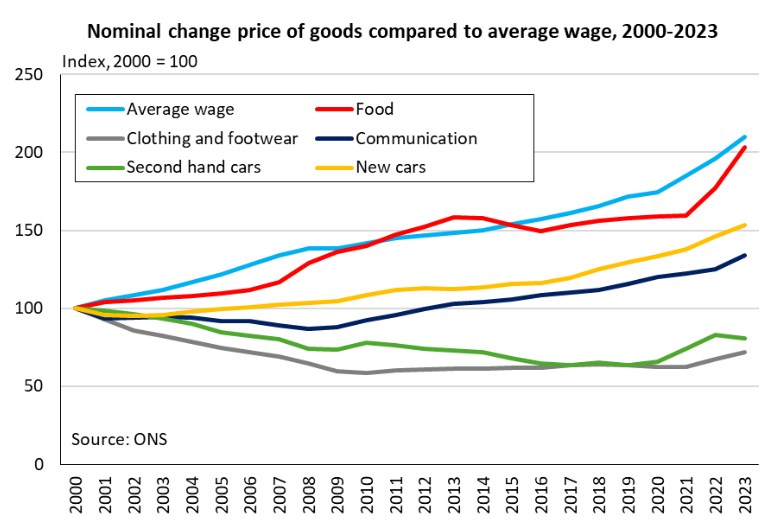

For example, while the price of the basket of food used by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in its Consumer Price Inflation (CPI) index has increased in nominal terms, it has increased by roughly the same amount as the average wage over recent years, so has stayed more or less steady in real terms – as per the graph below.

.

Meanwhile, in both nominal and real terms, clothes and used cars cost less today than they used to 20 years ago. New cars and communications equipment are also cheaper in real terms, and given technological advances, likely to be better as well. Whatever the downsides of globalisation, international trade and competition in relatively open markets has been a boon for British consumers.

But in other areas, we are much worse off. And it’s mainly those where supply has been constrained by government policy, particularly energy and housing, which have seen massive increases in prices since 2000.

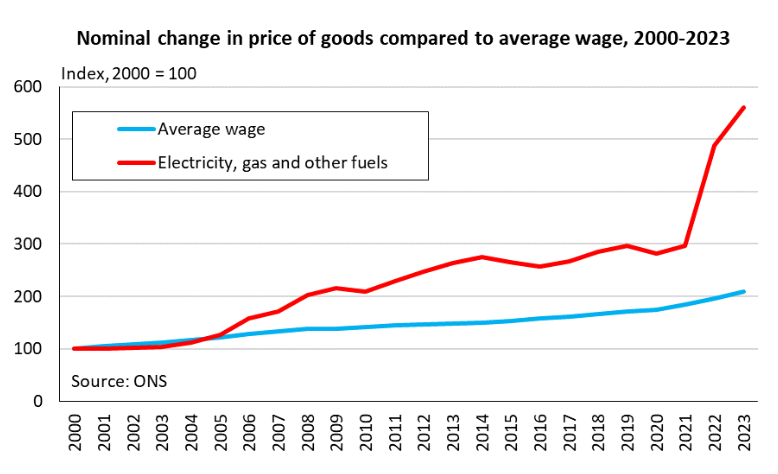

Energy is now five and half times the price (in nominal terms) than it was in 2000, but the average wage has only doubled in nominal terms. While energy prices spiked in 2022 following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, they had already risen substantially since 2000. In fact, we went from having some of the cheapest energy in the developed world to the most expensive. Other CPS colleagues have written before about how the price cap for electricity introduced under Theresa May has reduced competition and set a de facto market price in electricity market, hurting consumers.

Similarly, it is now widely accepted that over the last few decades, planning restrictions and Nimbyism have prevented the new wind and solar farms, grid connections, nuclear power plants and shale extraction which would have led to much lower energy costs in Britain than we see today.

.

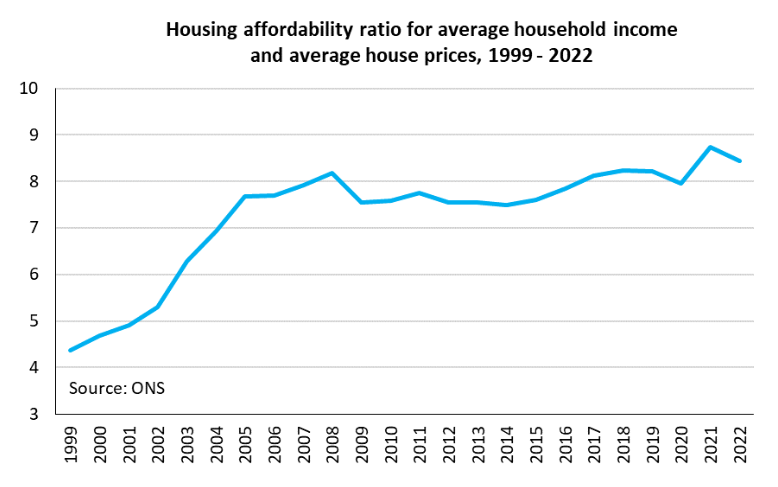

House prices rose significantly throughout the 2000s, and while there was some levelling off in the 2010s, the average house price is now almost nine times average household income, compared to just over four times the average income 25 years ago. The situation is even worse in places where there are the best jobs and the greatest demand to live. In London, the average house price is now 14 times average earnings.

Like energy prices, house prices have also been driven up by a lack of supply growth caused by a system of restrictive, anti-growth planning regulations. Many houses are just not built in the places they are needed, and Labour’s changes to how housing targets are calculated are only going to exacerbate this, cutting targets for places like London while increase targets in area like Cumbria, where the housing crisis is less acute.

Supply matters, and government intervention into markets tends to constrain supply growth. This hurts everyone. The history of the last 20 years shows that freer markets deliver better quality and lower cost goods. When it comes to consumer goods like food and clothing, the government has simply let the market provide what people want – and the result is cheaper food and clothing. But housing and energy are treated differently, and higher prices are the natural consequence.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.