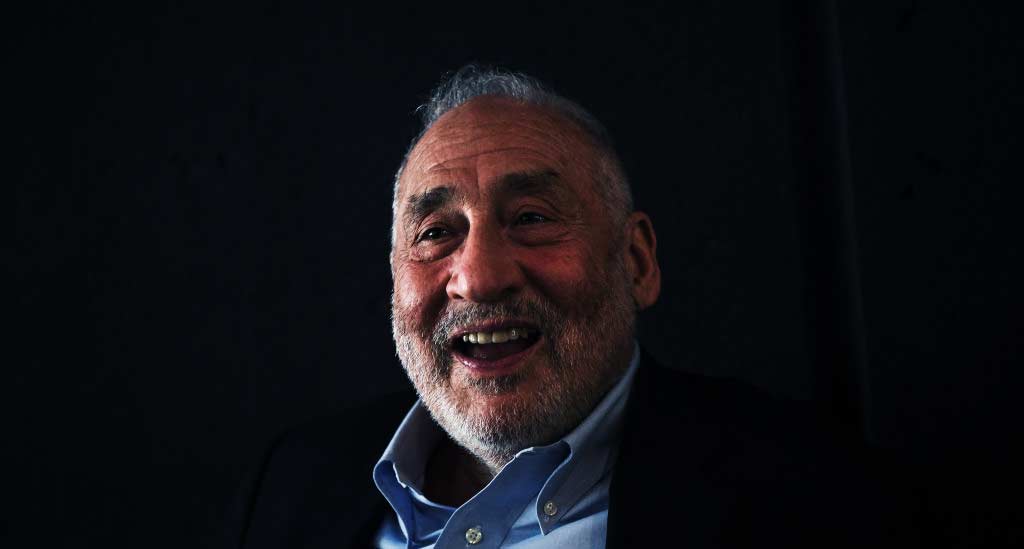

Joseph Stiglitz does not want for credentials. He is a recipient of the Nobel prize in economics as well as the John Bates Clark medal. He is a professor at Columbia and a former chief economist at the World Bank. Still, his latest book shows that such qualifications are no inoculation against bias or poor judgment.

People, Power and Profits: Progressive Capitalism For An Age of Discontent combines melodramatic warnings, anti-Trump polemic and a tired policy prospectus. While its diagnosis of rampant inequality and an out-of-control elite are familiar enough, the solutions Stiglitz advocates are worth paying attention to, not least because he is close to senior Democrats such as presidential hopeful Elizabeth Warren and New York Mayor Bill De Blasio.

Stiglitz is blunt about his aim, which is not just to make an economic argument, but to produce a platform he says “can serve as a consensus for a renewed Democratic Party” — an admission of partisanship that somewhat undermines his claim in the preface that he approaches questions of public policy “as an economist”. (So too does his remark in a recent interview that “the policies AOC talks about are the right policies”).

The book is split into two parts, the first a bleak appraisal of the state of his nation, the second a programme for sorting things out. For Stiglitz, unsurprisingly, the US is in dire straits and on the wrong path. A combination of decades of “market fundamentalism” since the Reagan years have led to inequality, despair and, ultimately, a populist demagogue in the White House. And worse may still be to come, with a tech-fuelled “dystopia” on the horizon unless decisive action is taken.

His description of a lack of investment, stagnant wages and a sense of despair, especially in post-industrial America, is not necessarily wrong. But laying all of the blame on “unfettered” markets seems both simplistic and overly partial. Similarly, while it’s perfectly reasonable to be concerned about the issues raised by social media and Big Data, the reflexive lurch to a doomsday scenario is as unhelpful as it is misleading. It also ignores the very many improvements that new technology has wrought on our lives, and the huge potential it has to make things even better in the future.

As is all too common in contemporary discourse, Stiglitz’s pessimism sometimes spills over into over-the-top rhetoric. On more than one occasion, for instance, he compares the way business is kowtowing to the Trump administration with the way German industry failed to stand up to Hitler — a trope we’ve become so inured to it’s often forgotten just how inappropriate it is.

While he doesn’t hold back on attacking Trump, the real villain of the piece is not the President, but the market.

Indeed, we learn that “many if not most of our society’s problems, from excesses of pollution to financial instability and economic inequality, have been created by markets and the private sector”. Free-marketeers are portrayed as swivel-eyed zealots with an “almost religious belief in the power of markets”.

If the market is the problem, the solution is a good dose of government, a theme Stiglitz turns to in the book’s second half. There are some sensible suggestions about reforming campaign financing, trying to de-politicise the judiciary and, especially in the Trump era, keeping America open to both people and ideas from overseas. Then there are the sort of populist leftwing measures, such as curbing executive pay, which are de rigeur for Democrats of the AOC or Bernie Sanders tendency.

The real meat of his proposals, though, is a big increase in government spending, not just on education and infrastructure, but also on a turbo-Keynesian “jobs guarantee”, combined with a “vastly strengthened unemployment insurance scheme”. There is precious little about either the cost in either tax rises or increases to the US deficit that his plans would involve. And without being given any projected figures, it’s hard to pin down the fiscal consequences of this expansion of the federal government’s remit.

There are all sorts of objections to both Stiglitz’s diagnosis and his proposed solutions. Reading People, Power and Profits, one is left with the impression that public spending is simply a one-way bet with nothing but upsides. There is no sense of a debate about allocation of resources, nor whether the federal government is best placed to distribute vast sums of its citizens’ money. Nor, either, is there any detail on how things stand at the moment – after all, it’s not as though Americans pay particularly low taxes, and the federal government already spends the equivalent of 21 per cent of GDP.

And while Stiglitz accuses rightwingers of a pie-eyed obsession with the power of markets, he exhibits exactly the same myopia when it comes to the power and efficiency of government. Take his argument that markets lead to pollution, for instance, which holds little water when one considers the massive environmental degradation wrought by statist regimes.

What’s also striking is the way he appears to contradict himself about the nature of markets. He uses the US example to argue that “unfettered markets” lead to inequality and overconcentration, but also describes his country’s economic system as “ersatz” and “misshapen” capitalism. This version of capitalism isn’t working well, he seems to be saying, but it’s also not real capitalism. Equally, he blames free markets for “many if not most” of America’s problems, while also listing a host of issues that have little to do with them — an iniquitous justice system, corrupt politicians, racism and poor educational standards, to name just a few.

Moreover, plenty on the right agree that a plethora of subsidies, paid-for politicians and competition-killing regulations have given rise to an economy where markets are not working anywhere near optimally. Plenty has been written, for instance, on the way American consumers are routinely ripped off buying everything from medicine to home insurance, with a handful of companies dominating markets at the expense of ordinary households.

This is not controversial stuff. After all, as Stiglitz himself notes, billionaire investor Warren Buffett has been quite open about his strategy of investing in companies that have regulatory “moats” protecting them from innovation and competition. This has also been described at length by Brink Lindsey and Steven Teles in their book The Captured Economy, which sets out how companies have played the government system to entrench their advantage and market power.

All of which makes Stiglitz’s charitable characterisation of the US regulatory environment all the more odd. The rules, he says, are set by “independent and accountable agencies” who “implement the intent of Congress as impartially as possible”. This is flatly at odds with the mounds of evidence that special interests have wrested their way into the very agencies that are meant to regulate them. It’s as though Stiglitz cannot bring himself to acknowledge that large parts of the US government – the mechanism he wants to bestow with ever more economic power – are not functioning anything like they should be.

Indeed, while Stiglitz might call his prospectus “progressive capitalism”, he is really just repackaging European-style social democracy. That means an ever bigger role for the state, higher taxes and a less flexible labour market (aka more “security”).

By all means argue for those policies, but don’t pretend that they have no consequences in terms of deficits, innovation and, in the case of many countries in the Old Continent, mass unemployment. Likewise, one might ask why it is the United States, not Europe, that has consistently produced the world-beating companies that have so many commentators so worried about a tech dystopia.

If there are answers to some of America’s economic problems, then, they are unlikely to be found in simply throwing more money into a political system that is plainly dysfunctional. Instead, a truly progressive, prosperity-enhancing agenda for America should focus on restoring real competition to both the economy and politics.

That means filling in some of Warren Buffett’s moats — rewriting regulations that entrench market power, which have helped push up prices while driving down wages and investment. It also means revisiting the issue of money in politics, so that those in Congress and the state legislatures are responsive not to vested interests, but to the interests of their constituents.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.