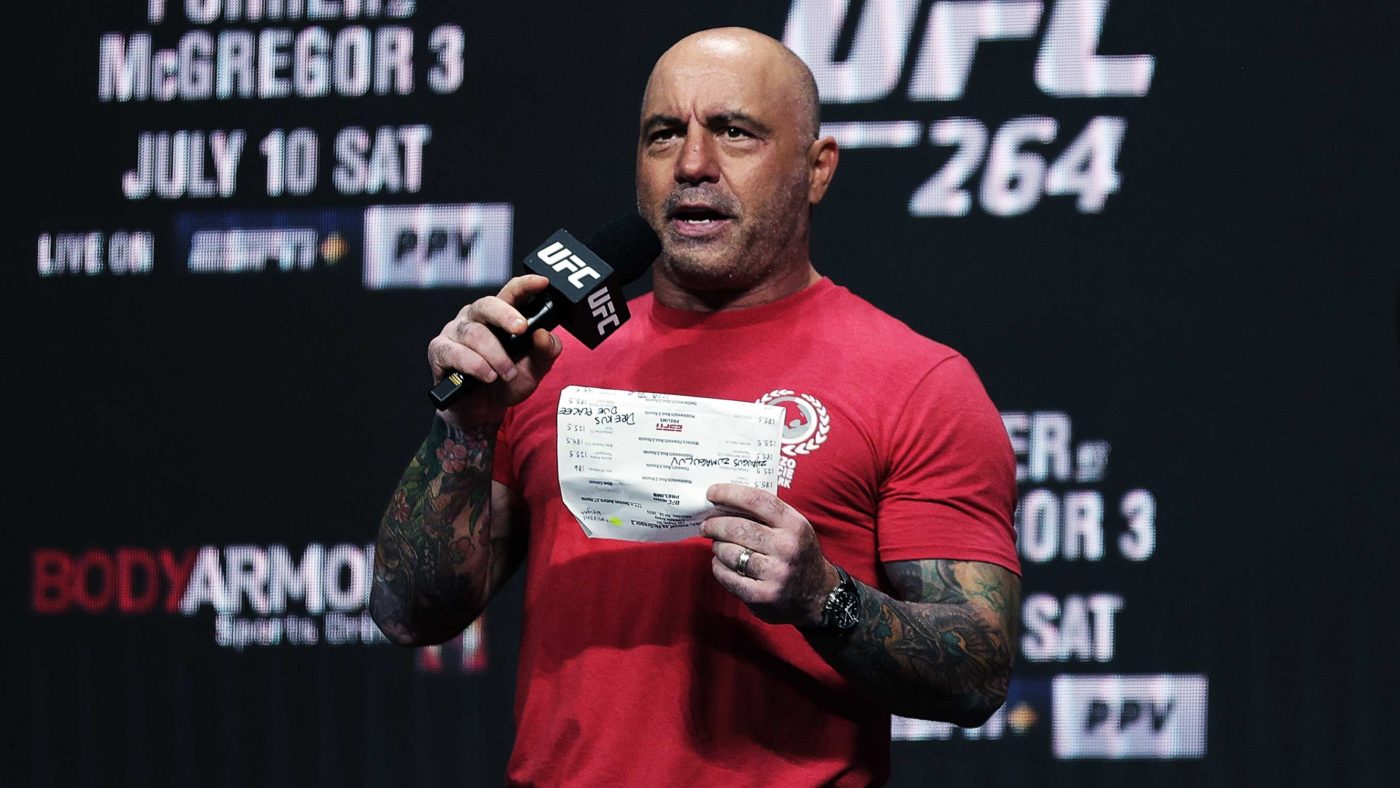

Joe Rogan – podcast host, comedian, and rather charmingly self-described ‘moron’ – has found himself serving as an unintentional illustration of the evolving hierarchy of progressive values, and the enduring power of linguistic taboos. Already embroiled in controversy over episodes containing disputed information on Covid-19, when a video compilation of Rogan saying the N-word started circulating on social media, the star was forced on the defensive.

Some 113 episodes of his show were subsequently removed from Spotify, with the company’s CEO describing the words as ‘incredibly hurtful’, and Rogan himself describing the incident as ‘the most regretful and shameful thing that I’ve ever had to talk about publicly’. The episodes that started the Covid controversy, however, are still on the site.

If I had to offer an explanation, it would run roughly like this: Covid-19 misinformation, real or merely alleged, is generally thought of as bad, and results in opprobrium. Certain words, however, are taboo.

In a 1934 essay, Allen Walker Read distinguished the taboo of concept – a topic it was forbidden to discuss – from the taboo of word (language which is inadmissible in society). At the time that he was writing, one word stood clearly above all the others as the worst you could commit to paper: ‘the most disreputable of all English words – the colloquial verb and noun… designating the sex act’. The other words alluded to by Read ran on a similar theme, relating to sex or excrement.

Today, those are very far from the worst words you could say in polite society. An unintentional ‘f*ck’ might get you told off, but saying a racial slur in a ‘heated gaming moment’ will get you fired. Alongside these taboo words, taboo concepts have moved on. Sex is now not only an acceptable topic to write about, it is practically a celebrated one. Blasphemy is commonplace. Common views on race, sexuality, and gender in 1930s America, on the other hand, are rather likely to be beyond the pale.

One way to look at this process is the substitution of old taboos and taboo words around blasphemy and sexuality – structures that work well in holding together homogeneous groups with strong interpersonal bonds – with taboos that work to evade pointing out differences and intergroup tensions, and hold together more diverse societies with lower levels of commonality.

Think about the worst words you can say in the English language. Such is the level of opprobrium attached to their use – regardless of whether in discussion or deployment – that even indicating them with letters and asterisks can be insufficient; they are instead referred to by their starting letter. To the ‘N-word’, we can sometimes add the ‘Y-word’, the other ‘F-word’, and to an – American audience at least – the ‘C-word’.

When the American linguist John McWhorter published an article discussing the history of one of these words, the New York Times felt it necessary to preface his text with an editor’s note warning the reader that it ‘contains obscenities and racial slurs, fully spelled out’.

The common element between each of them is that they point to issues of race, gender, and sexuality, and rules on their deployment usually bind those outside the indicated subgroup. To the extent that blasphemy is a commonly considered to matter in polite Western society, it is generally not with regard to how we talk about Christianity, but Islam – in other words, once again where words act to point to differences between groups.

This may exist in part because of the conflation of taboos of word and concept; some topics should not be discussed, some words become associated with those topics. This link between words, ideas, and indeed abuse is partly what drives the ‘euphemism treadmill’; as new words are coined and become linked with the same issue.

In the US, for instance, the word ‘negro’ made way for ‘colored;, ‘colored’ made way for black, black for African-American, which in turn made way for black again and then the capitalised Black. The language may have evolved, but the core issue of pointing to a distinct group within society, and all the baggage that comes with this labelling, has not gone away.

Joe Rogan thought that using the N-word word would be OK, because ‘as long as it was in context, people would understand what I was doing’. But that isn’t how taboos work. You can’t use the word in a ‘non-racist’ way, because breaking the taboo is itself considered to be racist. It doesn’t really matter why you break them, just that you have. In extreme cases, even saying words that sound like the taboo word can get you in hot water; Professor Greg Patton learned that the hard way when he taught students about the Chinese word “na-ge”, and was promptly investigated by his university.

Somewhat perversely, it’s at least partly the strength of rule against their use that preserves the place of taboo words in our collective vocabulary. Rather than simply falling into disuse, the ‘thrill of doing the forbidden’ or of using the strongest possible language keeps them in circulation; taboo words are, predictably, easier to recall than ‘normal’ language. There are certainly exceptions to this rule (notably, we appear to have forgotten the proper name for bears), but the idea of self-sustaining taboos is not without merit; even arguing about the appropriate boundaries of taboos is a somewhat risky business.

Read, for his part, ended his essay by arguing against the ‘taboo of word form as separated from the taboo of concept’; if a topic is fit to be discussed, then otherwise inappropriate words can be referred to. That was roughly the position Joe Rogan took – that taboo words were admissible if used to illuminate a discussion on a non-taboo topic. He has now abandoned that defence, saying simply ‘there’s nothing I can do to take that back’.

To a degree, Rogan’s experience tracks the journey society as a whole has taken; it is very difficult, for example, to imagine the Washington Post publishing this review some 20 years on.

That is, on balance, probably an improvement. And if you are inclined to disagree, remember that doing so would also be taboo.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.