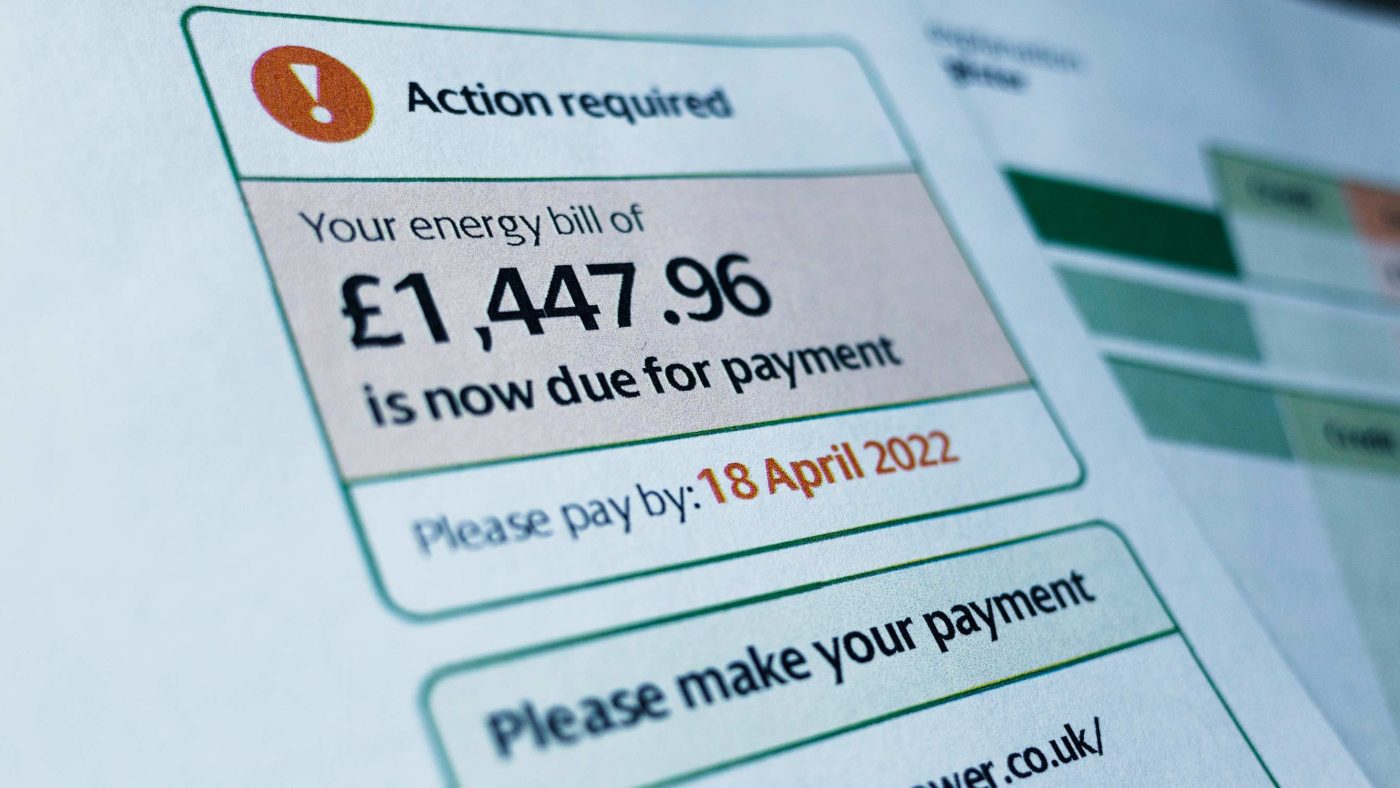

The last few years have seen extraordinary changes in the energy markets. Prices spiking to levels that would have been unthinkable just a short time ago. The Government stepping in to directly subsidise energy bills at a staggering cost to taxpayers, and round after round of supplier failures, with the costs pushed onto consumers.

But there’s a very important aspect of this crisis that has mostly flown under the radar – competition has all but disappeared from the retail market. Before the energy crisis, you could make substantial savings on your bill by switching tariffs or suppliers, but now competitively priced rates are nowhere to be seen. While volatility in wholesale prices certainly has a lot to do with this, there’s another culprit in the mix – Ofgem’s Energy Price Cap (EPC).

Like so many government interventions, it was introduced with the best intentions and was only ever meant to be temporary. The price cap was designed to tackle the ‘loyalty penalty’, whereby customers who had been with a supplier for many years were getting ripped off on their bills. For those savvy enough to shop around there were big savings to be had, but for those (often elderly customers) who found this process too confusing or complicated (or those rolling off a discounted ‘acquisition tariff’), a supplier’s standard variable tariff was often terrible value for money.

So the price cap was introduced (following from an earlier cap for those on prepayment meters), essentially as a proxy for competition for those who couldn’t ‘engage’ in the market. The cap was meant to be Ofgem’s best guess as to what a ‘fair’ price should be for such customers, and to genuinely function as a cap, with competition thriving below this level. And of course this was only ever meant to be temporary, while the Government put in place other initiatives to tackle disengagement, such as the smart meter rollout and improved switching processes.

For the early years of the cap (2019-2020) this is indeed how it worked. And then the energy crisis changed everything. With wholesale prices skyrocketing, many of the ‘fly-by-night’ suppliers went bust. They were undone by their risky business practices, certainly, but also by the rigidity of the EPC, whose six-month review periods were too infrequent to allow suppliers to adjust their prices to match wholesale volatility (Ofgem subsequently updated this to quarterly).

Moreover, the EPC level quickly became the cheapest price in the market rather than a cap, as fixed tariffs (not covered by the EPC) became ever more expensive, before most suppliers finally pulled them. Switching rates thus fell off a cliff and now nearly the entire market is covered by the EPC, with rates set at or just below the capped level. And of course the Government stepped in with the Energy Price Guarantee last winter (superseding the cap), until it expired in June.

Competition in the market has thus all but disappeared. Yes, a few fixed price deals have started to trickle out, but for the most part they are priced within 1% of the capped level. That in itself is partly by design; Ofgem is so concerned about the risk of supplier failures stemming from wholesale volatility that it has activated a measure known as the ‘Market Stabilisation Charge. This requires suppliers to reimburse each other any time a customer switches (at a weekly rate set by Ofgem), in order to guard against financial losses from the hedging requirements of the EPC. In other words, Ofgem is directly disincentivising competition in the market in order to safeguard suppliers’ finances.

These and other contortions are designed to make the EPC work in a world it was not designed for. Fundamentally the EPC was conceived of in yesterday’s (benign) market – in today’s world it is self-evidently no longer fit for purpose. Experts warn that higher prices could be with us throughout this decade and beyond, while volatility could well return this Winter if the weather doesn’t cooperate and Putin decides to play tricks. If so, this is a recipe for another ‘temporary’ intervention to become permanent, while the public becomes used to the state setting the price of energy, undoing much of the hard work of privatisation.

True, if markets do return to stability, competition could start to emerge under the cap. But our regulatory regime cannot be based on the hope that markets ‘normalise’ – and even if they do, the price cap reduces the incentive to compete (part of the reason it was always meant to be temporary). Moreover the current regime discourages innovation and is incompatible with our future energy needs, such as more dynamic ‘time-of-use’ tariffs (critical for our net zero efforts).

That is why in a new Centre for Policy Studies briefing note we call for the Government to abolish the price cap in its current form, helping to stimulate competition, lower prices for consumers and fight inflation. We discuss other ways the Government can tackle the ‘loyalty penalty’ in a less damaging way, such as making the current ban on acquisition-only tariffs permanent, or the idea of a ‘relative tariff’.

Moreover, reforms to the price cap should go hand-in-hand with expanded support for lower-income and vulnerable customers. A world of higher and more volatile prices means that the Government cannot rely on ad-hoc solutions, leaving customers to wonder how much support they’ll receive. Using the benefits system to determine eligibility (as is the case with current programmes) creates the risk of cliff-edges, and does not cover everyone who might reasonably need support. The Government should thus bring in a ‘social tariff’ as many have suggested, with more sophisticated targeting aimed at those spending an excessive proportion of their income on energy bills.

Fundamentally the Government needs to build a resilient regime which more effectively balances support for vulnerable customers with thriving competition. After all, as any economics textbook will show, the best protection for consumers is competition, not state price controls.