During his campaign for the presidency, Donald Trump promised to put the interests of American workers and taxpayers first, and to rebuild America’s creaking infrastructure.

At the same time, he has argued in favor of reducing America’s overseas commitments and insisted that America’s allies contribute more to their own defense.

So might this not be the right time to scale back America’s foreign aid expenditures and focus on humanitarian relief instead?

USAID was established in 1961, bringing together a number of different government programs dealing with technical and financial assistance overseas.

In the 1970s, USAID started focusing on delivery of healthcare and nutrition. In the 1980s, the agency purportedly tried to promote free market solutions to underdevelopment. Since the 1990s, it has focused on democracy-building and “sustainable” growth.

Today, the Agency’s mission is to “partner to end extreme poverty and promote resilient, democratic societies while advancing our security and prosperity.”

As such, the Agency’s remit includes promotion of trade and economic growth (i.e., development), agricultural productivity and food security, democracy and human rights, education, gender equality and women’s empowerment, global health, clean water and sanitation, and reduction of conflict, extreme poverty and the effects of climate change.

It now employs close to 10,000 people, 6,000 of whom live and work abroad, and spends a budget of $22.3 billion.

The legacy of foreign aid is, at best, controversial. While benefits of foreign aid, such as a new hospital or school, are readily seen, the costs of foreign aid are largely unseen. Chief among them is the fact that foreign aid has been a disincentive to reform

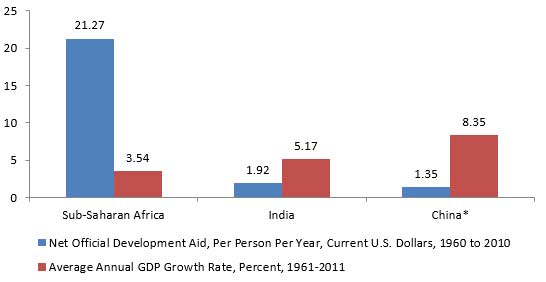

Governments that can count on aid from overseas do not need to change their domestic policies to encourage growth, or their political systems to encourage government accountability. Globally, there is no correlation between aid and growth. In Africa, it appears to be negative.

Much foreign aid is based on the “vicious cycle of poverty” theory, which argues that poverty in the developing world prevented the accumulation of domestic savings (i.e., people in poor countries consumed all of their income and had nothing left to save and invest).

Low savings resulted in low domestic investment, and low investment was seen as the main impediment to rapid economic growth. Foreign aid, therefore, was intended to fill the apparent gap between insufficient savings and the requisite investment in the economy.

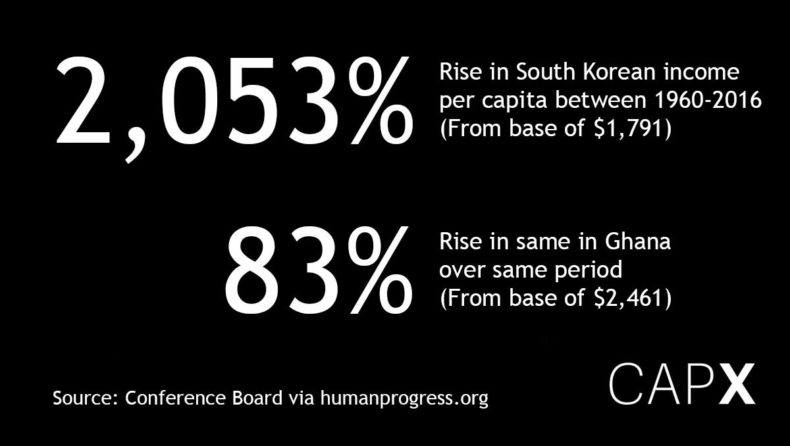

Yet experience contradicts the “vicious cycle of poverty” theory. Today, many formerly poor countries enjoy high standards of living, while others have stagnated.

For example, the 1960 per capita income adjusted for purchasing power parity in South Korea was $1,791. In Ghana it was $2,461. Beginning in the 1960s, South Korea embraced capitalism. Ghana, in contrast, experimented with socialism. Over the next 56 years, South Korea’s income rose by 2,053 percent and reached $38,571. Ghana’s rose by 83 percent and reached $4,495.

Countries that improve their policies and institutions – by increasing their trade openness, limiting state intervention in the economy, building a business-friendly environment, and emphasising protection of property rights and the rule of law – tend to grow faster than others. Such countries also tend to attract foreign capital, which can help to increase economic growth.

Improvement in policies and institutions also creates a suitable environment for growth in domestic investment. As trust in institutions such as the rule of law and protection of private property grows, people feel more confident investing in the local economy.

Moreover, the size and the scope of global capital markets make poor countries’ access to capital easier than at any time in the past.

Unlike in the past, when African governments borrowed almost exclusively from official creditors such as the World Bank and the IMF, today Africa owes roughly half of its $250 billion debt to private creditors – thus eliminating yet another putative reason for the continuation of foreign aid.

Note the difference between foreign aid, such as the budget support for foreign governments that has often led to waste and corruption, and humanitarian assistance, such as disaster relief.

Generally speaking, Americans are among the most generous people in the world. According to the respected Index of Global Philanthropy, published by the Hudson Institute in Washington, D.C., American private philanthropy in 2013 came to $39 billion – $8 billion more than the total amount of aid that the U.S. government sent overseas under the auspices of USAID as well as other government agencies, such as the Department of State.

Strictly speaking, therefore, American humanitarian assistance could revert to being fully voluntary. Should Washington insist on continuing to send U.S. taxpayer money overseas, Mr. Trump could ask Congress to create a U.S. humanitarian fund.

The money for the fund would be appropriated via the regular budgeting process, invested in the market in order to appreciate, and drawn from in case of emergencies, such as tsunamis, famines, earthquakes, etc.

To preserve political accountability and prevent mission creep, the Fund could be overseen by a panel consisting of an equal number of House and Senate members of both parties, and decisions could be made by a super-majority.

For-profit companies as well as NGOs could apply for funds in order to relieve suffering of the people in the stricken areas. Competition between them would encourage speed and quality of delivery, as well as cost-efficiency and transparency. Congressional evaluation of services delivered would weed out underperforming entities.

U.S. government spending is unsustainable and ought to be reduced. The USAID budget is a tiny portion of overall government expenditure, but that does not mean that foreign aid should escape Mr Trump’s scrutiny.

Ultimately, America can cut its foreign aid budget and still remain a generous contributor to the alleviation of true human suffering.