Consistency has never been one of Boris Johnson’s biggest strengths. Take Research and Development funding: Johnson wants to double the Government’s science budget over the next few years to some £22 billion a year, committing Britain to spending 2.4% of GDP on science. This will, to quote the newly published Integrated Review, secure our status as a “Science and Tech Superpower” by 2030.

As a downpayment, Johnson has committed £800 million of our money on a new agency called ARIA (the Advanced Research and Invention Agency.) Yet today, even as you read this, other parts of the British Government’s science budget are facing cuts of over £1 billion. For two reasons.

First, we’re cutting the overseas aid budget from 0.7% to 0.5% of GDP, so £120 million is being excised from the research that is currently supporting our aid programmes to third world health and economic development.

Second, our withdrawal from the EU deprives us of the £1 billion or so of European research grants; and though the Government says it will compensate by adding a further £1 billion to its science budget, it hasn’t. An awful lot of scientists are currently looking at redundancy.

Which is wonderful. No, seriously, I’m not being sarcastic. It’s wonderful.

This is what happened in the US in 1973 when Senator Mansfield made the scientists at ARPA (the Advanced Research Projects Agency) redundant. Consequently they streamed out to Silicon Valley’s XeroxPARC to invent the mouse, windows, pop-up menus, the trash can – indeed, the graphical user interface – and the laser printer. And where they pioneered an Ethernet network and sent things called ‘emails.’

Thanks to those redundancies at ARPA, Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple were forged in America, not Britain or Europe – and it’s the US that harvested the profits and the jobs from Big Tech.

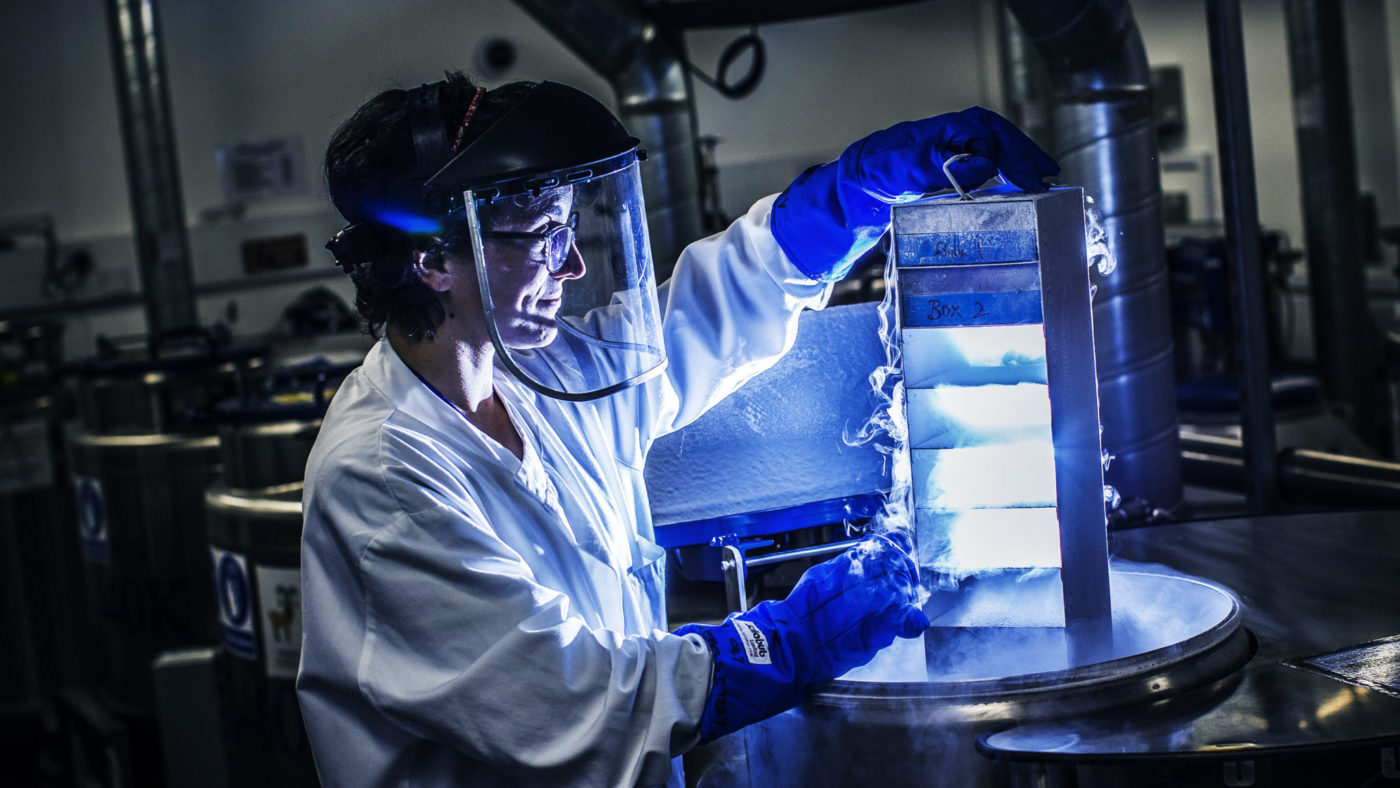

The only bright spark in the last 12 months in the UK, as 126,000 of our fellow citizens have died prematurely, as the economy and our social lives have tanked, and as the Government has been repeatedly exposed as incompetent, has been the vaccine programme run by Kate Bingham.

She has been to vaccines what Lord Beaverbrook, the newspaper proprietor, was to fighter production during the Battle of Britain. In May 1940 Churchill recognised the public sector could never supply Fighter Command with enough fighters, so he installed Beaverbrook as the Minister of Aircraft Production; and Beaverbrook – harnessing the entrepreneurial flair of the private sector – performed such wonders that the RAF was never short of aircraft. Pilots, yes; aircraft, no.

But for Bingham, Britain’s vaccine response would have been like the EU’s: cautious, cost-obsessed, legalistic and slow. But Bingham was imported from the private sector, were she’d worked as a venture capitalist and where she’d learnt to be bold, cost-effective, purposeful and fast.

Bingham read biochemistry as an undergraduate, so imagine if she’d been seduced by a vast Johnson-inspired programme of scientific research into doing a PhD and into staying in university science. She’d now be a distinguished professor, and tens of thousands of our fellow citizens would currently be dead or anticipating death.

One issue is ‘crowding out’. There is only a limited number of good scientists, and if the government sequesters them into the universities, industry is crippled.

The other issue is the market. It’s proprietary knowledge that keeps one company ahead of another, so the one activity companies will never neglect is R&D.

Which is why there is absolutely no evidence anywhere, any time, that state funding of research has done anything but slow a nation’s rate of economic growth by pulling the best scientists out of industry into universities.

Much angst has been expressed in recent years over the lack of productivity growth in the US and UK. But that is naïve. Industrial R&D flourishes when alternative sources of profit are blocked, which is why companies spent more on R&D during the Great Depression than any time before or since.

But during the 1970s and 1980s the US and UK globalised, and companies consequently found easy sources of profit in cheap labour (whether in outsourcing production to cheap labour abroad or in importing cheap labour), so they’ve naturally cut back on R&D.

To invoke Adam Smith, R&D and productivity are only means to an end, namely GDP-per-capita, and since globalisation has generated that for us, we’ve bypassed all that onerous research. But industry would flip straight back into it should its access to cheap labour be curtailed.

So while the overall trend is towards greater government spending, pundits are still wringing their hands over the forthcoming redundancies of hundreds or even thousands of government-funded scientists. But I say bring them on! Let all those newly-redundant researchers invigorate British industry and save us from economic decline, Silicon Valley-style.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation