Humanity is winning the war on HIV/AIDS. Deaths from the disease are down. The same goes for new infections. More people then ever have access to cheap and effective antiretroviral therapy. Chances are that, in the foreseeable future, a cure or a vaccine will deliver the once terrifying disease a final coup de grâce.

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a range of progressively worsening medical conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) that, if left untreated, usually culminates in death. In the main, HIV spreads through unprotected sex, contaminated blood transfusions, hypodermic needles, as well as from mother to child during pregnancy, delivery and breastfeeding.

Scientists believe that HIV is an offshoot of the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) — a virus that attacks the immune system of monkeys and apes. It is thought that the virus “jumped” from simians to humans in the 1920s when Congolese hunters came into contact with animal blood.

First documented cases of people infected with HIV include Congo in 1959, Norway in 1966 and the United States in 1969. In its early days, the disease spread primarily within the gay community, with infection rates of 5 per cent among homosexual men in New York and San Francisco in 1978.

HIV/AIDS was first covered by the mainstream press in 1981 and named one year later. Over time, it has come to affect everyone, with heterosexual men and women accounting for the vast majority of the 76 million people who were infected with the virus and 35 million people who have died from AIDS over the last 40 years.

Considering that HIV is spread, in large part, via sexual intercourse, its destructive potential became obvious very quickly. Consequently, scientists throughout the world have been working on treatments, vaccines and cures for the better part of the last four decades.

The first drugs slowing the progression of HIV appeared in the mid-1990s. Today, it can be treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), which not only slows the progression of the virus, but decreases the risk of HIV transmission from one person to another.

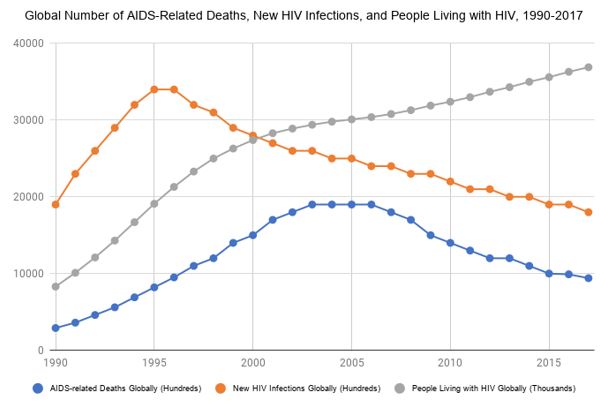

The HIV pandemic peaked in the mid-2000s, when some 1.9 million people died of AIDS each year. In 2017, less than one million died from the sickness. In the mid-1990s, there were some 3.4 million new HIV infections each year. In 2017, there were only 1.8 million new HIV infections. In 2017, 37 million people lived with HIV of whom 59 per cent had access to treatment.

Today, sub-Saharan Africa accounts for nearly two-thirds of all people living with the virus. The prevalence of HIV peaked at 5.8 per cent in 2000 and stands at 4 per cent today. The region accounts for nearly two-thirds of all people living with the virus. Of those living with HIV, 44 percent have access to HAART.

In 2000, HAART cost more than $10,000 per patient per year. “Within a year,” the United Nations found, the price “plummeted to $350 per year when generic manufacturers began to offer treatment. Since then, owing to competition among quality-assured generic manufacturers, the cost of treatment continued to fall.”

In 2016, it stood at $64 per patient per year, with much of the money coming from Western aid programmes such as the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

What does the future hold? So far, the virus has proven fiendishly difficult to eradicate, so we should exercise caution about new medical breakthroughs. That said, today we know more about the disease than ever before and scientists are, probably, closer than ever to a cure or a vaccine.

Late last year, for example, doctors using a treatment called Nivolumab, a cancer drug that was developed by Medarex and brought to market by Bristol-Myers Squibb, noticed a “drastic and persistent” decrease in HIV-infected white blood cells. An HIV vaccine may also be on the horizon after scientists showed that a new drug developed by scientists at Harvard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and The National Institutes of Health triggered a protective immune response in humans and stopped two thirds of monkeys from becoming infected.

The critics may argue that four decades is a long time to tackle HIV. That, however, is historically illiterate. Smallpox, polio, mumps, Guinea worm disease and malaria have been the scourge of humanity for millennia. Today they are are all either eradicated or treatable. Forty years from an outbreak of a pandemic to treatment and, hopefully, eradication is but the blink of an eye.