This week, I learnt something genuinely startling.

I was on the BBC with Rupert Harrison, former chief of staff to George Osborne, to discuss the Tory manifesto. Asked about the “tax lock”, I said I hoped it would be junked: yes, low taxes are great, but it was a naked electoral gimmick that imposed unwise limits on government’s fiscal flexibility. Rupert’s response? “It’s a fair cop.”

Afterwards, on Twitter, I asked him about the triple lock on the state pension. Was that also bad policy? Yes, he said. In fact, it only got into the Coalition Agreement because the Treasury said it would cost just £50 million a year.

absolutely. A lib dem demand that we accepted in coalition negotiations after being told by HMT it would cost £50m…

— Rupert Harrison (@rbrharrison) May 17, 2017

It’s fair to say that this was something of an underestimate. In 2016-17 alone, as Daniel Mahoney wrote on CapX, the policy has cost an extra £7.4 billion – the equivalent of 13 large state-of-the-art hospitals.

This astonishing gap between expectation and reality didn’t just emerge because the Treasury is terrible at forecasting – though it is.

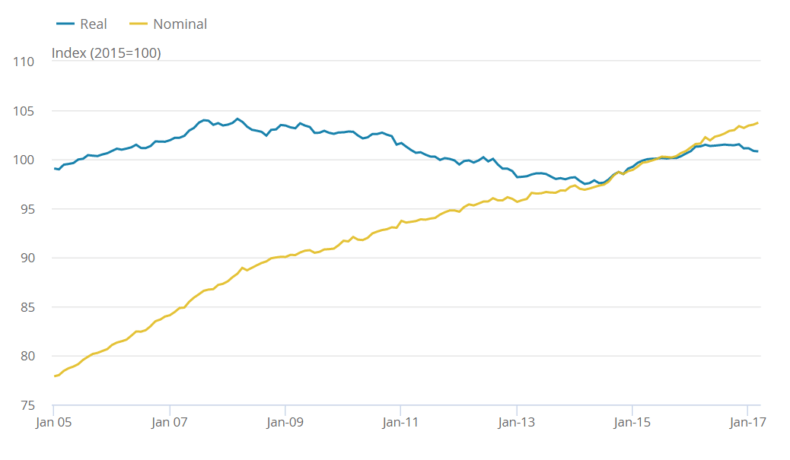

The triple lock guarantees that pensions will rise by the highest of CPI inflation, earnings or 2.5 per cent. But even as inflation spiked after 2010, real wages remained falling or stagnant. Traditionally, higher employment would lead to higher wages, as the labour market tightened. Instead, whether because of workers’ nervousness about asking for pay rises or the easy availability of immigrant labour, Britain has combined a remarkable ability to create jobs with an utter inability to turn those jobs into higher salaries, as this ONS chart of UK wages shows.

The result of this, fairly obviously, was an increasing divergence between old and young. Pensioners had their benefits uprated; those of working age saw their salaries frozen and benefits slashed. That’s why the triple lock was unfair, and why Theresa May was right to ditch it.

But this is far from the only difference between the generations, or even the most important.

As Faisal Islam of Sky News pointed out yesterday, more people in England now own their own homes outright than have a mortgage.

Number of English homes owned outright without mortgage, overtook those mortgaged in 2013 – this was a significant shift for politics etc… pic.twitter.com/xAyjwCc49Y

— Faisal Islam (@faisalislam) May 18, 2017

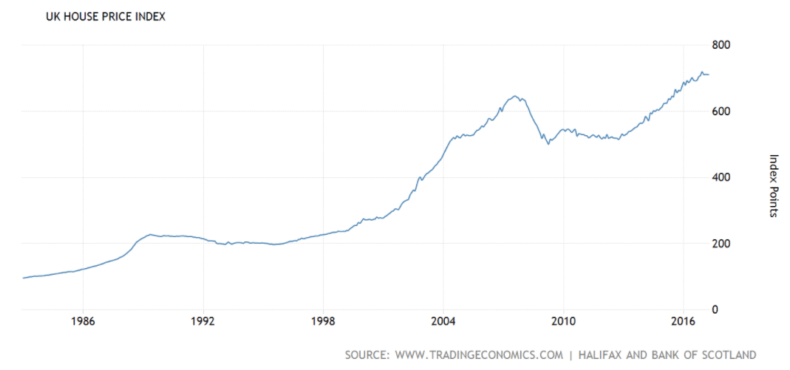

This is not only renders them relatively immune to interest rate fluctuations. It means they have become, over the past few decades of soaring house prices, massively wealthier.

The people owning those homes are overwhelmingly likely, as the latest data from the Social Mobility Commission shows, to be elderly. Indeed, over the last 25 years there has been an extraordinary shift in terms of home ownership away from the young and towards the old.

Ouch. Ouch. Ouch. Ouch. (Stats via @SMCommission) pic.twitter.com/nedQdIrzlD

— Robert Colvile (@rcolvile) March 27, 2017

Which brings me, by a roundabout route, to the Tory manifesto.

Many people have already pointed out the extent to which it confirms Theresa May’s tilt away from free-market orthodoxy – something I pointed out earlier this week.

But apart from its explicit repudiation of small-government Conservatism, the manifesto’s most significant point was the extent to which, despite its lack of specific costings and vagueness about the expected tax rises, it was a document intended to grapple with the real world rather than the fantasy land of its authors’ imagination.

A few weeks ago, remember, we were being told to expect something vague and fluffy, stronger on principles than policies. Instead, we got a serious document for serious times.

And one of its most serious, and most important, themes was this imbalance between the generations. Because as the data above show, we really are two nations. Those who own, outright, homes which have grown enormously in value – and those who may never have the chance to.

And yes, I appreciate that there are poor pensioners and rich youngsters. But generally speaking, those born in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s have been handed a winning ticket in the lottery of life, even if – to the baffled fury of their sons and daughters – they don’t quite seem to appreciate their good fortune.

This is why Paul Goodman of ConservativeHome was right (as he so often is) when he wrote this morning that the manifesto represents a triumph for grown-up government.

Paul, like me, has his qualms about May’s more interventionist ideas, not least the awful energy price cap. But he recognises that we should credit her for grappling, in the fourth of the manifesto’s five sections, with these big issues of generational unfairness, with a world in which the average pensioner is earning more than the average worker.

May could have done the electorally sensible thing: keep the triple lock and universal winter fuel payments and all those other delightful bungs which have tilted the playing field away from the young and towards the old.

But she didn’t. She recognised that something needed to be done – even if it would allow Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell, who came to power as the champions of Generation Rent, to complete their (unconvincing) transformation into the pensioners’ protectors.

John McDonnell launches Labour's punchy new election poster. pic.twitter.com/WifToHjI9l

— Kevin Schofield (@PolhomeEditor) May 19, 2017

The greatest controversy, inevitably, has come over the Tories’ plans for social care – in particular, the idea that people might have to fund long-term treatment using the housing wealth they have accrued. It transgresses on so many of the great social shibboleths – the idea that an Englishman’s home is his castle, the desire to pass on a nest egg to your children, the belief that the NHS should be able to care for everyone, for free.

Yet at the same time, it is a brave and probably necessary step. Not least because, given the scale of spending that is required on social care, that vast pot of accrued housing wealth may be the only place to find it.

Inevitably, there will be unfairnesses – some will pass on properties to their children early, others will die of cheaper illnesses and so still have more wealth to leave. And it’s obviously worse for those with expensive long-term conditions than the modified version of the Dilnot plan to which the party was previously committed, which saw care costs capped at £72,000.

But as Torsten Bell of the Resolution Foundation wrote in his analysis of the proposal, “Theresa May could not both be the person protecting housing wealth and the person offering an answer to one of the big challenges of our time. She has chosen the latter.”

For supporters of the free market, there are many things to chew on in Mrs May’s manifesto, from its paeans to interventionism, to its solid clarity on Brexit, to (as George Trefgarne points out) its relative silence on the importance of business.

But ditching the pandering to pensioner power – even at the risk of ballot-box consequences – is surely the bravest and most necessary change to her party’s stance.