There is no viable route to decarbonising transport without electric vehicles. Getting people out of their cars and onto bikes, buses and pavements is a good idea for many reasons (air pollution, congestion, health, to name a few), but it simply won’t be enough to get to Net Zero. And any attempt to cut emissions by cancelling new road projects will need to reckon with the fact that even in 2050 most emissions from driving will come from the 100,000s of miles of road that were built decades ago.

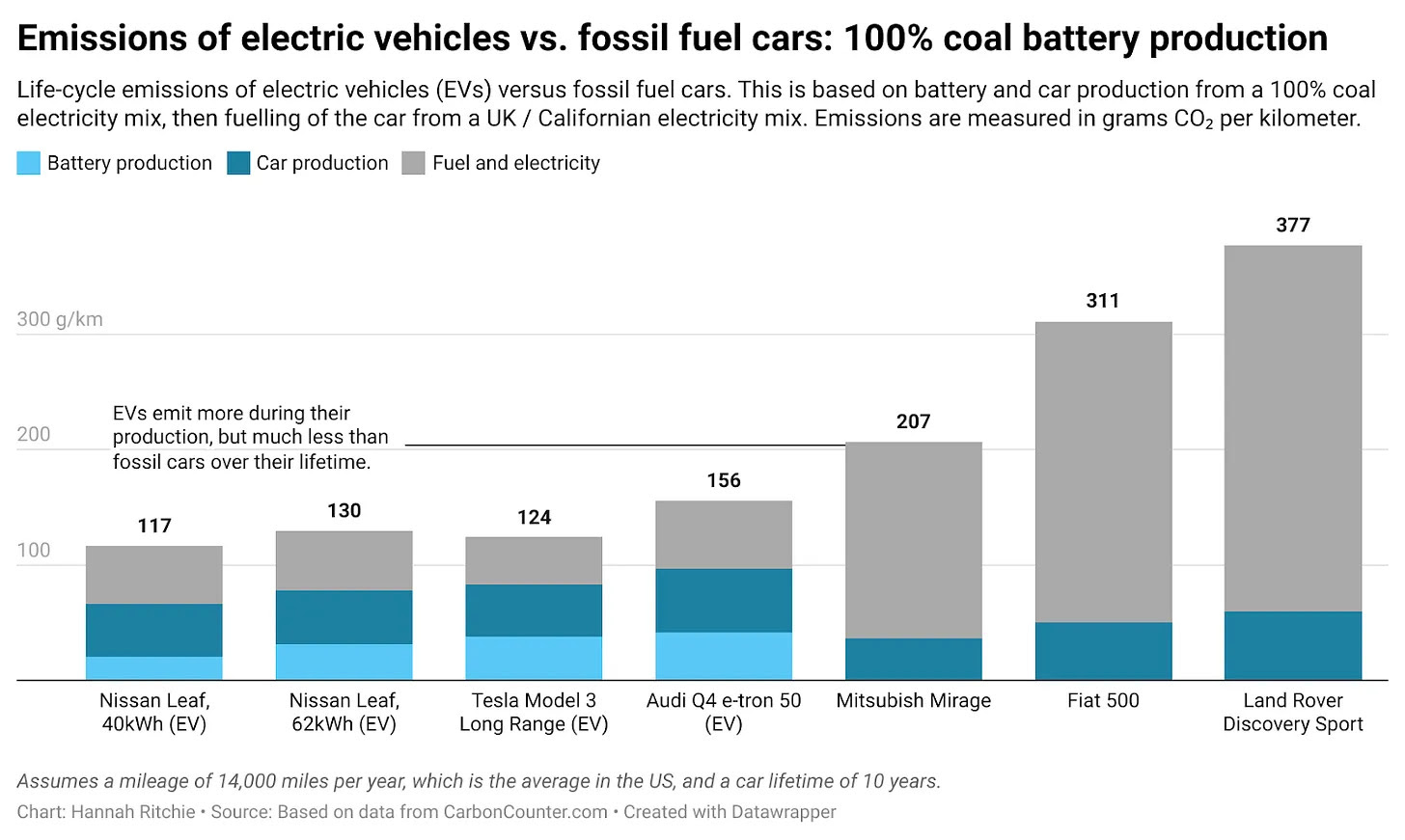

Contrary to what you may have read in the papers, electric vehicles are actually good for the environment. EVs don’t just eliminate tailpipe emissions, they convert energy into motion much more efficiently. In other words, they’re greener even if you’re using the same dirty source of power.

From Hannah Ritchie’s Sustainability by Numbers Substack:

‘For every dollar of petrol you put in, you get just 20 cents’ worth of driving motion. The other 80 cents is wasted along the way – most of it as heat from the engine.

‘Electric cars are much better at converting energy into motion. For every dollar of electricity you put in, you get 67 cents of driving motion plus another 22 cents of energy that’s recovered from regenerative braking. That means you get 89 cents’ worth out.’

It is true that more carbon is often emitted when EVs are manufactured, but EVs soon make up for it. In fact, it takes just under two years of driving (or 13,500 miles) for a Tesla Model 3 to make up for its extra emissions in manufacturing compared to a petrol car. And as grids get greener as more renewables replace gas and coal, the crossover point will continue to drop. For instance, the 13,500 miles figure is based on the US grid, where 23% of electricity comes from coal-fired plants. Norway’s close-to-fully renewable grid brings the crossover point down to just 7,800 miles.

And EVs would still be cleaner than petrol and diesel cars even if EV manufacturing was 100% coal powered. Now, that’s clearly not true of EVs made in Europe and the US, but it’s not even true of EVs made in China where 60% of power comes from coal.

.

Some EV batteries can go as long as 190,000 miles without experiencing a more than 10% drop in performance, which means we are looking at large emissions saving over the life of the vehicle.

And fears about an over-reliance on rare earth minerals that can only be mined in dictatorships appear to be going the same way as fears about peak oil. As demand has increased, new substitutes have been developed and new deposits have been discovered. Norway recently uncovered a massive deposit capable of meeting global demand for phosphate ore, which is needed for fertilisers, solar panels and electric car batteries, for the next 50 years.

***

A few factors will determine the pace of the EV rollout, the most important being cost. On this front there’s good news. EVs are yet to reach price parity with petrol or diesel cars, but prices are falling fast.

The key reason EVs typically cost more than petrol cars is the cost of the battery. But over the last 30 years, the unit-cost of lithium-ion batteries has fallen by 98%. Most of that decline has come in the last decade. In 2010, it cost between $30k to $60k to produce an EV battery. It now costs between $5k to $12k. And there is no reason why we can’t continue to find more efficient ways of producing batteries.

We are fast approaching the point where new EVs are cheaper than new petrol or diesel cars. Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates that as early as 2025 a new EV will cost the same as a petrol or diesel car. Once you take into account the fact EVs have much, much, lower running costs, the choice to buy an EV won’t just be the greener choice, it’ll be the cheaper choice too.

But new cars are only part of the story. Four-fifths of cars sold in Britain are used and people tend to hold onto their cars for longer these days. Used cars are important not just because there are more of them, but because of who drives them and the way they are driven. A recent study from the Breakthrough Institute’s Ashley Nunes points out that the emissions savings of switching from a used petrol car to a used EV are greater than the emissions savings from buying a new EV instead of a new petrol car.

There’s two reasons why. First, there are no emissions in manufacturing for a used car – so provided the EVs have been on the road for a year or so before being sold second hand, drivers cut emissions from the first mile they drive. But, more importantly, used cars tend to be driven more than new cars. One reason is that new car buyers are, on average, much wealthier than used car buyers and can afford to own multiple cars. And because they own multiple cars and spread their miles across them, they tend to take longer to hit that crossover point and save fewer emissions as a result.

Inflation Reduction Act-style subsidies for new EV purchases don’t look like a good idea as a result. We are unlikely to avoid many emissions by subsidising a high-earner living in Hampstead who uses their EV to commute into the congestion charge zone (EVs don’t pay it) and take advantage of parking spaces reserved for EV charging. And chances are, most EV purchasers at the moment will have made the purchase anyway. Schemes targeted at stimulating the used car market are likely to deliver more bang-for-your-buck. What those schemes would look like, however, is far from clear.

There are two other key factors: range and reliability. Motorists won’t buy an EV if they’re scared it will run out of juice on a long journey and they have to make an embarrassing phone call to the AA because there is nowhere to charge it. Range anxiety, as it’s known, is gradually being addressed by the market. A new Tesla Model Y will get you from London to Durham on a single charge with change to spare. But, a more affordable Nissan Leaf will still require a charge mid-way through, though to be honest, unless you have a bladder made of steel you should probably budget for a stop at a service station anyway.

But, at the moment, most motorists don’t only make big trips when they have a full tank of petrol. The ability to keep your vehicle at full or close-to-full battery each night is tricky for people lacking a driveway. At least, it is in some parts of the UK. While there are 145 public charging points per 100,000 people in London, the number falls to 53 in the North East and just 33 in the North West. This disparity is set to get worse with most 2 in 3 new public charge points planned for London. If the switch to EVs is to happen at pace, then the rest of the country will need to match London. In the space of a year, the UK’s gone from 16 EVs per public charger to 32 EVs per public charger. For context, the EU reckons that a ratio of 10 EVs per public charger is what we should aim for.

So what can be done to make charging an EV easier and more reliable?

One suggestion, recommended by the Climate Change Committee, is to cut VAT on public charging to 5%. At the moment, when EV owners charge their cars at home they pay a reduced-rate of 5% VAT, but when they charge elsewhere they pay the full 20% rate. One concern that has been raised by Adam Corlett at the Resolution Foundation is that this is fundamentally unfair and regressive. After all, wealthier households are more likely to be able to charge their car at home. The regressivity aspect is less of an issue at the moment as EV owners as a class tend to be well-off, but it will become a growing issue when EVs become the norm.

But recently, a group of tax experts have cast doubt on whether this would actually improve the affordability of EVs. Their key concern is that there’s no guarantee that EV chargers will actually pass the tax savings on to motorists. They cite two recent cases where suppliers pocketed the tax saving.

‘There were two recent VAT cuts resulting from high profile campaigns, and where industry pledged that consumers would benefit: the May 2020 abolition of VAT on ebooks, and the January 2021 abolition of VAT on tampons. Tax Policy Associates has used ONS data to assess the actual impact on prices, and found a result consistent with the literature referenced above: all or almost all the benefit was retained by suppliers.’

The Climate Change Committee’s report on VAT for EV charging states that chargepoint operators should “allow any potential savings from reduced VAT rates from electricity for public charging to be passed onto the consumer, and not taken as additional profit.” This is, as the letter puts it: “naive.” Businesses are not charities and will charge whatever the market will bear.

What the research on VAT tends to show is that savings are least likely to be passed on when they’re focused on specific products or services – a broader based cut such as for all hospitality is more likely to be passed on – and in markets where competition is weak. Both apply to EV charging. As the expert letter notes, EV chargers don’t appear to compete on price with home chargers and at any given location options for EV charging are limited.

Of course, if chargepoint operators do pocket the tax cut as profit it might incentivise them to install more chargepoints. This just would be a relatively inefficient way of incentivising chargepoint installation with most of the tax cut rewarding business for how many charge points they have already installed not how many they plan to install in the future.

***

Instead of focusing on short-term tax breaks or subsidies for purchase, the priority should be on making it easier to install chargepoints so when prices do come down and people make the switch the infrastructure is already there for them. On this front, there are two key barriers: grid and planning.

Grid

Across Britain, housing developments, solar farms, and data centres are all held up by the need to secure a grid connection. Due to outdated regulation, waits can be lengthy with one solar farm quoted a 13 year wait.

As a result, when a chargepoint business wants to set up in an area they need to check what the remaining grid capacity is. Essentially, they don’t want to invest scarce funds into a new chargepoint that no one can actually use. The Times recently reported that a new EV fast-chargepoint in Scotland has been built for months, but cannot actually be turned on due to grid delays.

The problem is not just that the grid has been slow to expand, but also that finding out where the grid does have capacity isn’t straightforward. What a chargepoint operator wants is an easy to use online portal that provides information on which sub-stations have capacity to spare. At the moment, only two electricity distributors (UK Power Networks, which covers London, the South East and the East, and Western Power Distribution, which covers the South West, Midlands, and Wales) provide this information freely.

In the North West, which coincidentally has the fewest number of chargers per 100,000 people in the UK, chargepoint operators have to send an email to Electricity North West and then wait 30 days (some companies tell me the 30 day target is often missed) for a response about whether a specific substation has capacity. If it doesn’t they either have to go back to the drawing board and ask about a separate substation, or pay a massive upgrade cost. If the rest of the UK adopted the same model as UK Power Networks and Western Power Distribution, all of these unnecessary and costly delays could be eliminated.

It is within OfGem’s remit to require all of the remaining electricity distribution monopolies to publish open capacity data for all of their substations and make them accessible online. This would speed up the EV rollout at minimal cost.

Planning

If you happen to have somewhere to park your car off-street, acquiring planning permission to install a chargepoint is relatively straightforward. There’s a Permitted Development (PD) right for installing one, so as long as you meet certain standards (i.e. it’s not too tall, too chunky, or too close to a public highway) you do not need to apply for planning permission.

This is not the case for public chargepoints. If a business wants to install new chargepoints so people can charge while they park on the street, then they need explicit permission from the council.

In theory, this shouldn’t be a big issue. New housing generates opposition because existing residents typically lose out in some way (e.g. more congestion, lower house prices, loss of light), but chargepoints are literally a new benefit for local residents.

Yet, there have been a number of recent objections against chargepoints being installed on public roads. In Norwich, where plans to install 46 chargers on city streets were under consultation, a local branch of the pedestrian campaign group called Living Streets described the proposal as ‘a new threat to our public space with more clutter on the pavements‘. Living Streets, along with charities representing the blind or partially sighted, have lodged similar objections to a Scottish consultation which suggested creating a PD right for on-street charging.

Living Streets want on-street charging points to be placed in the road to ensure no pavement is lost (Cambridge already does this). Yet, a compromise clearly could be struck. On narrow streets, more clutter is undesirable, but on wider streets where ample space for pedestrians remains – permissions should be streamlined and become permitted development where possible.

Another way to avoid pavement clutter would be to create a permitted development right to install special gutters for EV charging cables. Companies like Kerbo Charge will install small removable gutters running from your house to a parking spot. That’s handy if you have a regular on-street parking spot in front of your house. At the moment, this scheme is only being trialled in Milton Keynes, but there’s no obvious reason why it couldn’t be rolled out nationwide.

As it stands, EV charging businesses are complaining that under-staffed planning teams are taking too long to address applications and holding back the rollout as a result. Anything to make the process more automatic will free up planners time to deal with more complicated applications.

In an interview with Bloomberg, the CEO of Osprey Charging Networks was asked whether the Government was doing enough to support the EV charging rollout. Essentially asking is the £950m Rapid Charging Fund sufficient? His answer was telling.

‘We don’t need government money to build this infrastructure. We’re being held back by human resource delays. We have to jump through hoops to get planning permission, wait for grid operators to come and flick the switch at the site and wait for highways teams to approve designs for curbs. This is adding months and months to deployment.’

Many councils don’t even have plans for the EV rollout, despite having declared a ‘climate emergency’ and set extremely ambitious Net Zero targets. In fact, by my count, there are over 100 councils in Britain that fit this description.

Actions speak louder than words. If Britain’s infrastructure is to be fit-for-purpose for the EV revolution then we need more focus on removing the grid and planning barriers to charging and fewer virtue signalling bans on road building.

This article was first published on Sam Dumitriu’s Substack.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.