One of the key planks of the Coalition’s competitiveness agenda was corporation tax. Although their fiscal consolidation plan involved some tax rises – particularly on VAT – the headline rate of corporation tax was cut dramatically from 28 per cent to 20 per cent.

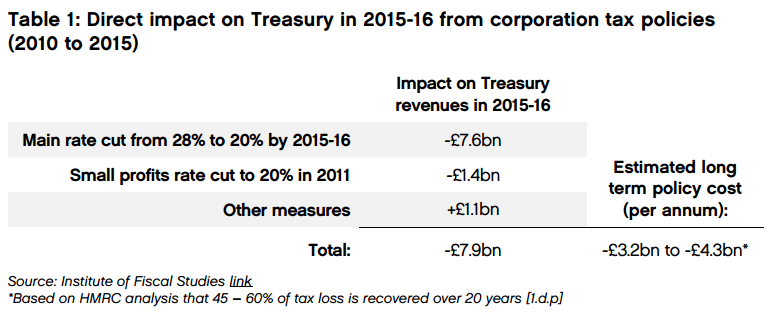

Traditional economic models imply that a fall in corporation tax will reduce revenue for the Treasury. As you can see from Table 1, when dynamic effects are accounted for, HMRC’s analysis suggests that the policy should cost the Treasury £3.2 billion to £4.3 billion per anum in the long term.

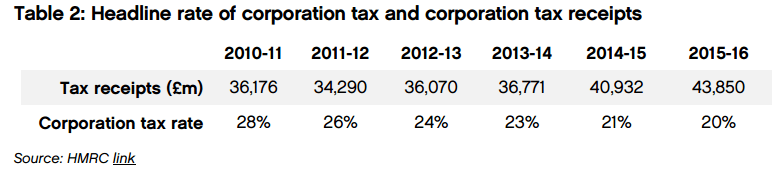

Yet despite this forecast, corporation tax receipts have, in fact, jumped since 2010. The economic slowdown did lead to a slight fall in 2011, but since then revenues have increased by 28 per cent.

So, why the discrepancy?

Any modelling of the impacts of specific tax changes cannot be viewed in isolation. The UK’s growing corporation tax receipts have arisen from two key factors: robust economic growth and more profitable companies, with, for example, the net rate of return on capital increasing from 10.2 per cent in 2010 to 12.2 per cent currently.

Both these trends have been as a result, in large part, of increasing competitiveness. The UK is now the seventh most competitive country in the world, according to the latest Global Competitiveness Index. That’s up five places since 2010. Britain has become more business friendly, which is why businesses are now more likely to invest in the UK and earn profits here.

While, this does not imply a direct link between higher corporation tax receipts and lower corporation tax rates, you can certainly link growing corporation tax receipts to growing competitiveness, which has, in part, been brought about by a fall in the headline rate of corporation tax.

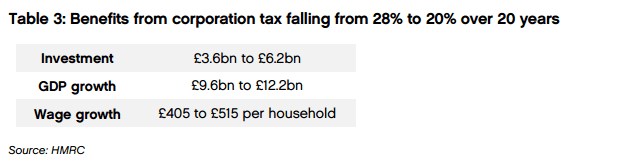

The Treasury has also confirmed that the fall in headline rate of corporation tax has led to a significant increase in investment, GDP growth and wage growth.

So, the case for cutting corporation tax rates is strong. Indeed, the intention to cut it again to 17 per cent by 2020 – which the Chancellor reiterated in his Spring Budget – will offer the UK a further competitiveness boost. It will be the lowest rate in the G20: “Sending the clearest possible signal that Britain is open for business.”

But as you might expect, Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party thinks otherwise. The Opposition wants to increase the tax rate by a further 1.5 points.

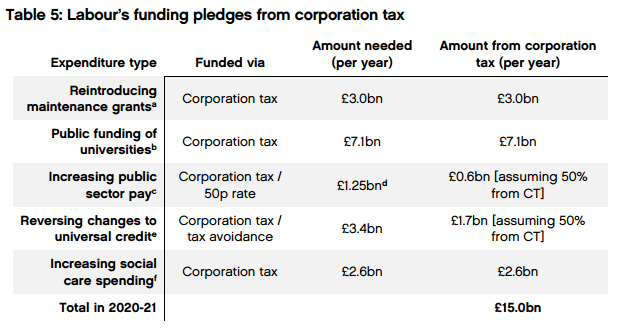

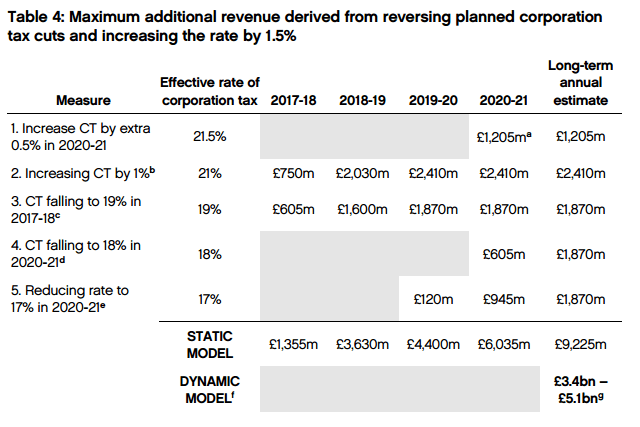

As I highlight in today’s Centre for Policy Studies’ report The Case for Corporation Tax Cuts, there are two key problems to Labour’s pledge. The first is that the revenue will be used to fund a huge range of policies, which equate to around £15 billion per annum.

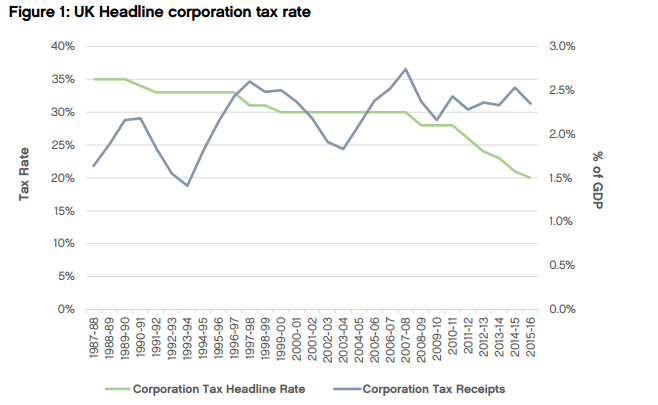

But all evidence points to the fact that increases in corporation tax rates do not necessarily raise any revenue. As you can see in Figure 1, below, a falling corporation tax rate has been associated with corporation tax revenues representing a higher proportion of GDP.

But even assuming that the receipts would raise money for the Treasury, it could only be a maximum of £5 billion a year in the long run. That leaves a £10 billion a year gap in their spending plans, at least.

In fact, even if corporation tax rates were increased to 28 per cent, there would still be a hole in Labour’s plans even in the most optimistic scenario.

There’s obviously a major economic credibility issue here. As Chris Philip MP, a member of the Treasury Select Committee, commented in response to the CPS’s publication: “This report shows Labour’s sums simply don’t add up, and is just the latest example of their economic incompetence.”

But, surely most important is the fact that such an increase would dramatically hamper the economy’s competitiveness. In conjunction with other anti-competitive policies, it would send a terrible signal to business, and the UK would become a far less attractive place in which to invest.

Any gains in investment, GDP growth and wage increases would be reversed. There would also be a negative impact on prospective jobs growth. And just as many developed economies are slashing their corporation tax rates, we would be raising ours. It just wouldn’t make economic sense.

The Government must stick to its guns on corporation tax – business, the economy and the taxpayer will all benefit.