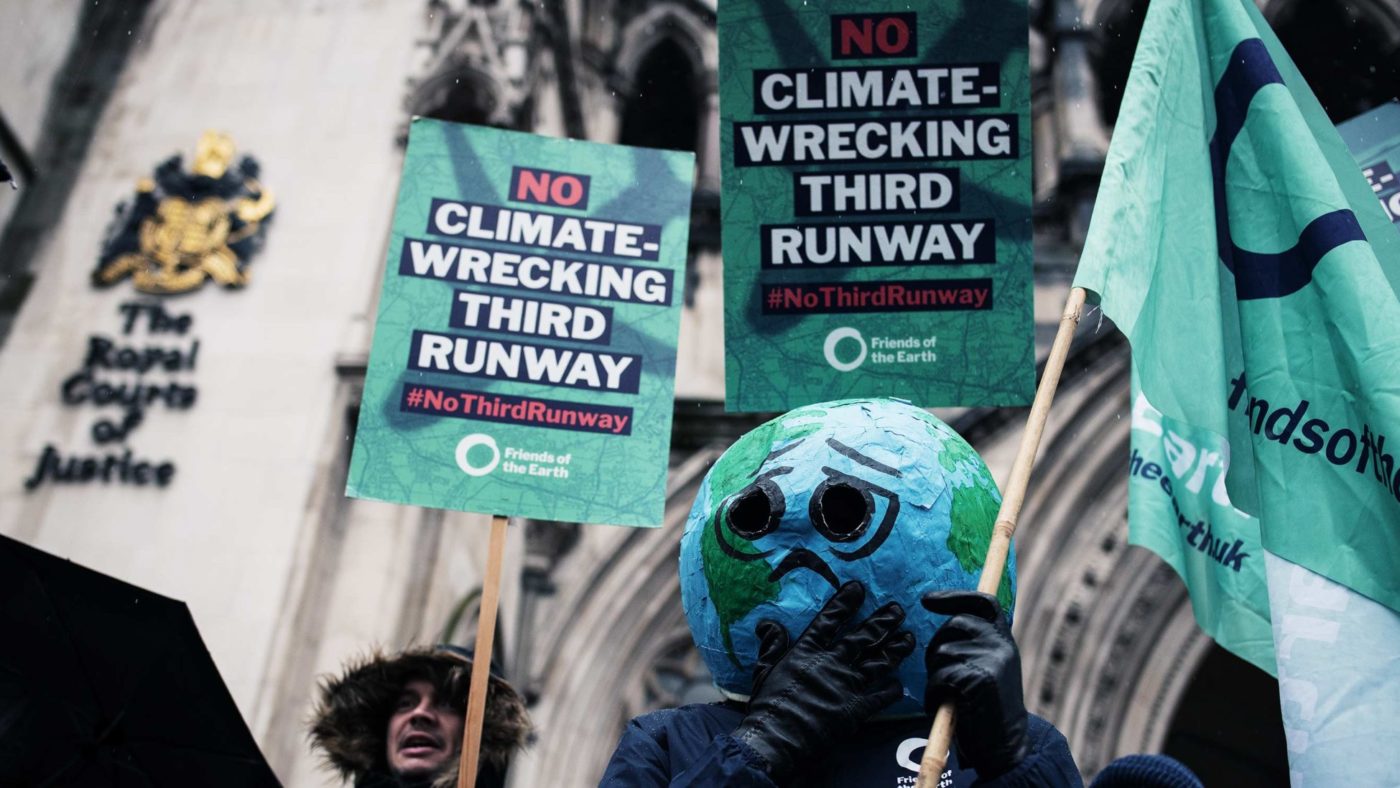

Yesterday’s court ruling against the plan to expand Heathrow Airport has elicited much wailing and gnashing of teeth about ‘judicial activism’ amongst sections of the right. Yet such complaints are legitimate only up to a point.

Whilst it is perfectly reasonable to oppose a system whereby major infrastructure decisions are so vulnerable to lawfare, in this case it isn’t right to accuse the judge of over-reaching. In this case the court simply did what the court is supposed to do: uphold the law.

As I have long argued, no accurate portrait of the growth of ‘judicial power’ is complete without recognising that a lot of the momentum behind this development flows from what might charitably be called the evolving habits of our legislators. Put bluntly, MPs have grown fonder and fonder of off-loading work to quangos whilst governments of all stripes have started to develop a taste for ‘legally binding targets’ or putting certain pledges ‘in law’.

It isn’t hard to see the appeal. Turning a target into a ‘legally-binding’ target is a great way of appearing a lot tougher on a given question without, in the immediate term, needing to drum up any extra money or actually do anything.

But legally-binding means, quite simply, ‘enforceable by the courts’. Thus a pledge cooked up to make a Prime Minister sound committed (or, heaven forfend, give them a ‘legacy’) can end up casting a very long shadow indeed.

Any government that were serious about combating the expanded role of the judiciary in our current constitutional arrangements would, as a matter of priority, conduct a review into all the legal obligations currently laid upon it by preceding parliaments and make a deliberate push for a shift away from this style. Yet so far as we know Boris Johnson still intends to enshrine NHS commitments in law. If a future legal challenge fouls up the Government’s health agenda, he’ll have nobody to blame but himself.

Following the agonised debate within the Conservatives over HS2, it’s now clear that infrastructure is perhaps the policy area which most brutally exposes the gulf between MPs’ abstract preferences and actual, detailed policy-making.

It does this in two ways. First, there is the blunt fact that big infrastructure projects tend to be very popular in principle yet somewhat divisive in practice. Second, because the sheer length of the timescales one must contemplate to properly analyse a major project (such as an airport) tends to shine a light on the implications of commitments such as ‘net-zero’.

That tweeter suggests that the Government is, as of last year, legally bound to pursue a CO2 emissions policy so stringent it would entail closing an expanded Heathrow – and that’s just the start of it. Easy enough for politicians to grandstand about now, but the courts now have a duty which is, realistically speaking, almost impossible to fulfil. A vast new frontier for conflict between the judiciary and the politicians stretches out before us.

Worst of all, it appears that very often politicians don’t even grasp the implications of what they’re signing up to. At the root of Heathrow’s defeat yesterday was the fact that the Department for Transport had simply decided to ignore the Government’s obligations under the Paris Agreement signed only two years before.

Regardless, this battered can – which had already been kicked down the road for so, so long – has now come clattering back to the Prime Minister’s feet. His immediate challenge is to try and find an alternative means of adequately expanding Britain’s airport capacity. He spoke often of ‘Boris Island’ before he had the power to get it built – will we hear much about it now?

But simply picking a runner-up in the runway battle is treating the symptom, not the illness. If Johnson wants to be remembered as a great builder of things, he needs to tackle the underlying causes of the UK’s increasingly abject record when it comes to major projects of this sort.

Yet will he do so? For all the fulminating about the judges, the simply fact is that they have done the Prime Minister a favour with Heathrow. No more awkward questions about when he’s finally going to get around to lying down in front of those bulldozers. Instead he can simply row back from Parliament’s decision to approve the expansion whilst Grant Shapps throws out chaff about it being “a private sector project”.

If Theresa May had been really serious about Heathrow, she could have attempted to put the project on a proper legislative footing with a Bill. This would have put the entire project on much firmer legal ground, not least because the additional scrutiny involved may have turned up the DfT’s fatally flawed reasoning. But that would have meant owning the plan in a way her Government was not willing to do.

The efficacy of the British system rests, ultimately, on the politicians. Short of farming out huge powers to an independent commission – which no government concerned with unelected power can seriously contemplate – things will only improve when those MPs who do want to get things built look each other in the eye and admit that “the fault, my Honourable Friend, lies not in our stars, but in ourselves”.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.