The University of Liverpool have announced they will be renaming Gladstone student halls – named after nineteenth-century Prime Minister William Gladstone – following an open letter from a group calling themselves ‘Students in solidarity with Black Lives Matter’ (SSBLM).

It appears that this decision was taken rapidly and secretively, without consultation with the wider university body. Unsurprisingly, there has been a backlash in the local media and on social media. Some have linked this to the removal of the statue of slave-owner and philanthropist Edward Colston in Bristol a few days prior. The contexts, however, could not be more different.

The demands of this small group of unrepresentative students set a worrying precedent and the university’s craven response shows a lack of backbone and, at best, a desire to avoid any potential negative media coverage or, at worst, a complete disregard for historical fact.

Why commemorate Gladstone in the first place?

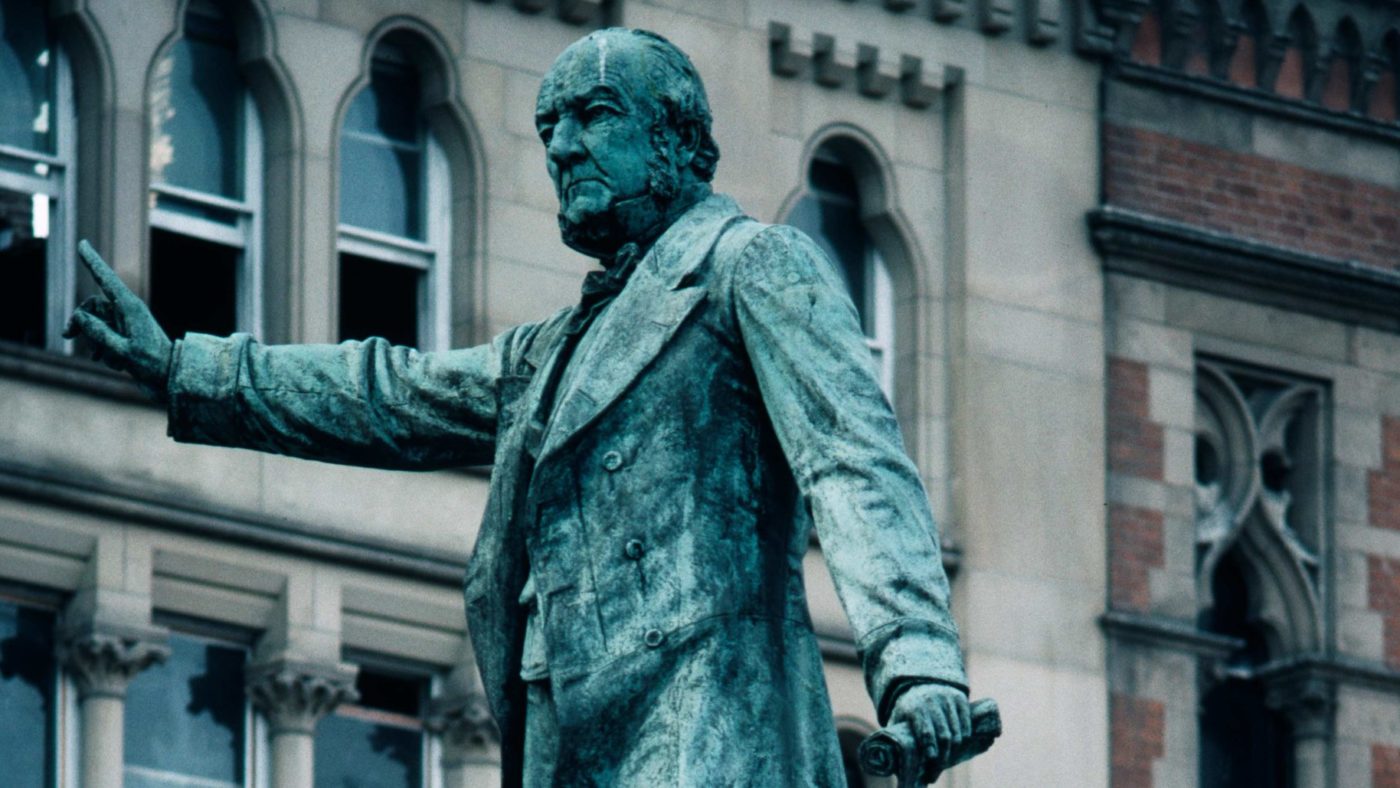

William Gladstone was a Liverpool-born four-time Liberal Prime Minister and Chancellor of the Exchequer. He bestrode the nineteenth-century, with a career lasting 60 years, and governments spread from 1868 to 1894 – ministries that helped shape Britain for the better. He introduced the secret ballot, expanded the vote amongst working-class men, legalised trade unions, introduced universal schooling from age 5 to 12, pushed for home rule for Ireland, fought against landlord and aristocrat privilege and almost single-handedly built the modern tax system. He was so popular amongst the working-class that he was known as “The People’s William”.

The irony is that if Gladstone were around today most students would have #GladWeCan plastered across their social media. He is undoubtedly one of the best politicians the city has ever produced (sorry Joe Anderson).

So what is the case against Gladstone?

The case against William Gladstone is weak and muddled. SSBLM’s open letter is long but there are only two accusations made against Gladstone, (after the false claim that Penny Lane is named after slave trader James Penny – there is no evidence for this).

The first claim about Gladstone is that his

“views on slavery followed in continuity with the views of his father, who was one of the largest slave owners in the British West Indies. Notably, William Gladstone’s earliest Parliamentary speeches regarded the matter of slavery. In the House of Commons on 3 June 1833, he used his position to defend the interest of those who, like his father, owned West Indian slave-ran plantations”.

It is undoubtedly true that Gladstone’s father owned slaves and plantations. But William Gladstone did not.

In the 3 June speech referred to above – one of his first in the Commons – Gladstone admitted he had “a deep, though indirect, pecuniary interest” in the issue of slavery but had “a still deeper interest in it as a question of justice, of humanity and of religion”. It is undeniable that Gladstone defended his father’s management of his plantation against attacks from the opposition, but it is also undeniable that Gladstone argued the cruelty of slavery provided ‘a substantial reason’ for abolition. Gladstone stated that

“we who had seats in this House and were connected with West India property, joined in the passing of that measure; we professed a belief that the state of slavery was an evil and a demoralising state; and a desire to be relieved from it”

In addition to this, William Gladstone heavily opposed the European rush to colonialize Africa, was a long-time critic of the slave trade (as, indeed, was his father who supported the candidacy of abolitionist William Roscoe in the 1806 general election) and, when he first stood for parliament in 1832 for the Newark seat, he told his electors that slavery should be abolished; “with the utmost speed that prudence will permit, we shall arrive at that exceedingly desired consummation, the utter extinction of slavery”.

Judging political figures from nearly two centuries past by the standards of today is questionable practice, but few would come out of an exercise as well as William Gladstone.

The second claim of Students in Solidarity with Black Lives Matter is that “Gladstone fought for a fair deal for the West Indian planters, and favoured economic prosperity over the freedom of the slaves that he and his father financially relied on”.

This is also true, but it’s no reason to cast Gladstone out as persona non grata. Great social reform requires compromise, especially that which goes against significant interests of powerful individuals. We see this in the negotiated peace between the Columbian government and FARC, or the painful compromises made in the Good Friday Agreement.

Paying reparations to slave owners is not the most morally satisfying way to end slavery, but it significantly eased the passage of the 1833 Bill. As academic Roland Quinault notes, the willingness of the West India planters to accept abolition was conditional on the receipt of substantial compensation for the loss of their slaves. They co-opted Gladstone on to a committee to consider the Bill to which he ‘acceded very reluctantly’.

This bill was passed because it worked within the dominant ideological framework of property rights. Any attempt to overturn this proprietarian ideology would have been met with heavy opposition from all corners of the legislature, and perhaps violence in the streets. In this case, the ends really do justify the means – what price would not be worth paying to free hundreds of thousands of slaves?

The SSBLM letter ends with the statement that “We can not facilitate normalising people like William Gladstone by naming our campus after them.”

To me, William Gladstone is exactly the type of person to honour – not only does he have an inspiring political legacy, with his governments enacting a series of reforms that markedly and materially improved working-class life, he also went against his family’s – and his own – material interests in order to do what was right and supported the abolition of slavery.

The strangest thing about this, however, is that a small number of students want to make the crimes of the father the sins of the child. This is a strange moral framework to have. Would they themselves accept that their position in university or at work would be dependent upon their parents’ good behaviour? Would these students make Jeremy Corbyn responsible for his crackpot brother?

Why the University of Liverpool’s response is wrong

This is not the first time students have tried to rename Gladstone Halls. In 2017, based on the same general misplaced arguments, students put forward to a motion to rename the Roscoe and Gladstone Halls. The Liverpool Guild of Students asked students ‘Should the Guild lobby the University to change the name of Roscoe and Gladstone Halls?’ and the proposition was defeated. Instead they decided to install an informative plaque.

This time, however, the change was announced directly from an anonymous University of Liverpool spokesman. There has been no democratic process for arriving at this decision. Instead, all the University says is that “A recent open letter from current students calling for the Hall to be renamed has further highlighted that this is an important issue within our University community” – but there is no mention of the numbers of signatories or whether they are actually students or staff at the University.

The backlash has come from all quarters. Current and former students, academics at the University like myself, Liverpool’s residents, and the leader of Liverpool Liberal Democrats, who calls the decision ‘tokenistic twaddle’. There is also a petition to #SaveGladstone, which you can sign here.

The University does, however, benevolently state that “The selection of an alternative name will be a democratic process involving students and colleagues across the University.”

My proposal? Rename it to ‘William Gladstone Halls’.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.