It’s rare for a party conference to be defined by the speech of a lowly delegate rather than by a leader or front bencher. But at the SNP’s annual gathering in Aberdeen yesterday, that’s what happened. And it happened in a peculiarly Scottish fashion.

Graeme McCormick spoke for the whole nation when he described his party’s latest independence ‘strategy’ as ‘flatulence in a trance’. Nobody quite knew what he meant by that, but the phrase caught everyone’s attention in the hall and had the added advantage that it almost rhymed. That the conference in question was the SNP’s and not that of one of its rivals added to the novelty. This is a party, after all, that has defined itself over the last couple of decades as the most disciplined and united in these isles.

But no longer. And the cause is clear: in the last twelve months, the SNP has pursued five different strategies for achieving its goal of independence. This time last year, Nicola Sturgeon was continuing to insist that repeatedly ‘demanding’ from Westminster the powers to hold a second independence referendum would eventually pay off. Then, faced with Rishi Sunak’s refusal to countenance such a thing, the then First Minister resorted to threatening a referendum without the authority of the UK government, something that her activists had long demanded.

But in order to progress that initiative, she was forced to consult the Supreme Court, just to check that her reading of the law on this score wasn’t completely wrong. It turned out it was, and their lordships told her so. The constitution was a matter reserved to the UK parliament and no referendum could legally go ahead without its imprimatur.

So then came strategy number three: to designate the next UK general election as a ‘de facto’ referendum, where the securing of 50% of Scottish votes cast would give the green light to immediate independence negotiations.

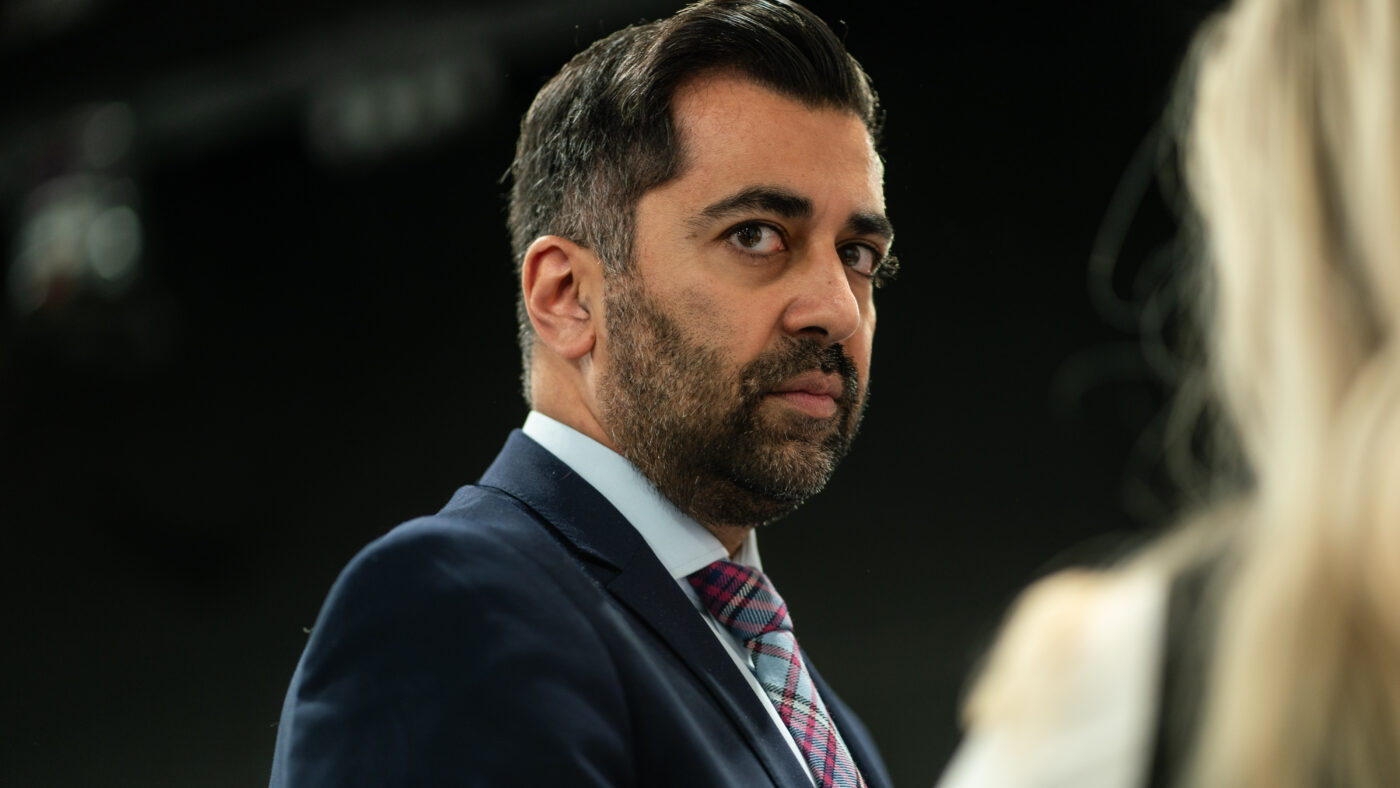

Then Sturgeon resigned in advance of her close encounter with Scottish police investigating the whereabouts of £600,000 donated to her party in order to fund the referendum that never happened, and Humza Yousaf took the reins of the SNP. Eyeing Sturgeon’s unattainable target of 50% of the votes at a general election, he conveniently decided that seats, rather than votes, would be a better threshold for those independence negotiations. If the SNP won ‘most’ of Scotland’s 57 constituencies at the general election, then that, he said, would be the mandate needed to embark on negotiations to destroy the United Kingdom.

But policy number four didn’t satisfy the conference, particularly nationalist MPs, who then forced an amendment demanding that only ‘a majority’ of Scottish seats, rather than a plurality, would empower independence negotiations.

Where to begin? And how long will Strategy Number Five last before the next one comes along?

Let us assume that Scottish Labour’s recent resurgence, as represented in its victory in the Rutherglen and Hamilton West by-election, is a false dawn, and that the next election sees the vast majority of Scottish seats once again fall to the nationalists. According to the SNP’s policy, that will open the doors to negotiations with the UK government on establishing an independent Scotland.

But what if the UK government doesn’t negotiate? And at the risk of offering a spoiler to CapX readers, it won’t. Why should it? The 2014 referendum was, as various SNP leaders have stated, the ‘gold standard’ for the independence process. Had the result gone the other way, Scotland would now be an independent nation and – crucially – recognised as such by the international community thanks to the clear and democratic process used to achieve it.

Whoever wins next year’s election will presumably be far too busy coping with its aftermath to indulge the SNP over its unilateral claims that have no legitimacy or legal force either politically or constitutionally. One side in a dispute deciding it has a mandate to negotiate places absolutely no obligation on the other side to participate. Let’s see how far Humza gets after half a day’s ‘negotiations’ with an empty room.

More importantly, the SNP has so little confidence in its own cause that it has abandoned any notion that more than half of Scotland’s voters would ever vote for independence. A majority, or even ‘most’ of Scotland’s seats can be won on significantly less than half the vote, as has happened at countless elections in the past. It would be damaging enough to the fabric of Scottish society to achieve independence on 50% of the vote plus one in a referendum; to demand it on the basis of 35% of votes cast in an election would be a grotesque distortion of democracy.

But this is where the SNP now is. Some will claim that it’s all Humza’s fault, that this dog’s breakfast of a policy, not to mention the dramatic episodes of indiscipline breaking out all over the place (amusing speeches by delegates at conference included) would never have happened under the leadership of his predecessor. This is to give Sturgeon far too much benefit of the doubt. This was a leader who strung her party along for years on the false promise of a referendum she must have known she had no authority to deliver.

The best and surest path to independence now would be – as at least some of the SNP’s more thoughtful parliamentarians are urging – to seek to persuade the Scottish people of the case for independence, and to take however much time is necessary to deliver a settled, large majority in favour of that change.

But the party has tasted the nectar of a referendum already; independence was almost within their grasp, until the dream was ruined by the Scottish people themselves. The SNP is not in the mood to be patient. It wants progress towards its dream now, today, and it will suffer no other strategy.

And that is why it is now on the cusp of a failure that could consign it to the fringes of Scottish politics for a generation.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.