Is certainty the new spending? When I talk to business, they often tell me that what they want, more than anything else, is certainty. And it isn’t hard to see why. These days government policy (and personnel) seems to change as often as the British weather.

The obsession with certainty can be overplayed. You rarely hear someone argue for sticking with a policy they think isn’t working for the sake of certainty. And entrepreneurs aren’t adverse to change, in fact, their frustration is often that long promised reforms, such as to the way energy markets work, are yet to be delivered.

Yet, investors’ expectations about the rate of corporation tax and how much of their investment they can deduct from it matter a lot. After all, businesses invest because they think they’ll make a decent enough return on their investment after tax.

In both cases, businesses have been on a roller coaster ride. When our new Foreign Secretary had his first stint in Government, the headline rate of corporation tax was 28%. Since then it’s fallen to 19% before shooting back up to 25%.

But, when you compare the headline rate to the base (i.e. what is and isn’t taxed by it), then it gets even more chaotic.

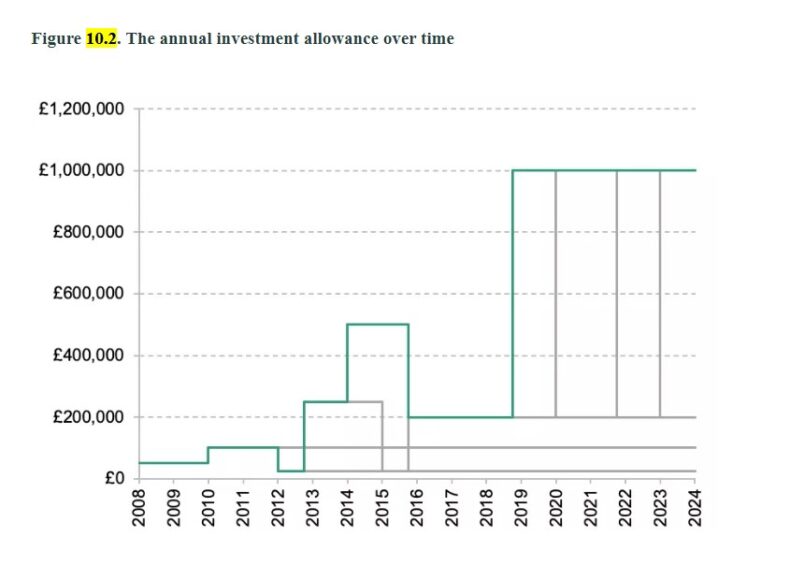

The Annual Investment Allowance, which incentivises SMEs to invest in new plants and machinery has jumped all over the place – changing no more than six times between 2010 and 2019. Each change was billed as temporary too.

.

The Annual Investment Allowance was made somewhat obsolete when Rishi Sunak as Chancellor announced the Super Deduction, a whopping 130% tax deduction for all qualifying investments in plants and machinery. Again, this was temporary and set to expire when Corporation Tax went up to 25%. Yet, at the very last minute, the Chancellor announced a new temporary policy of full expensing, allowing firms to deduct the full cost of any new investment in productivity-enhancing equipment from their corporate tax bill just like any other day-to-day expense. It means that for every pound they invest in qualifying plants and machinery, they can cut their tax bill by 25p.

It is a powerful pro-growth policy. A number of studies from Britain, the US and further afield suggest that full expensing could boost investment by almost 20%. It is no surprise business groups and think tanks have repeatedly made it their top ask ahead of every Budget.

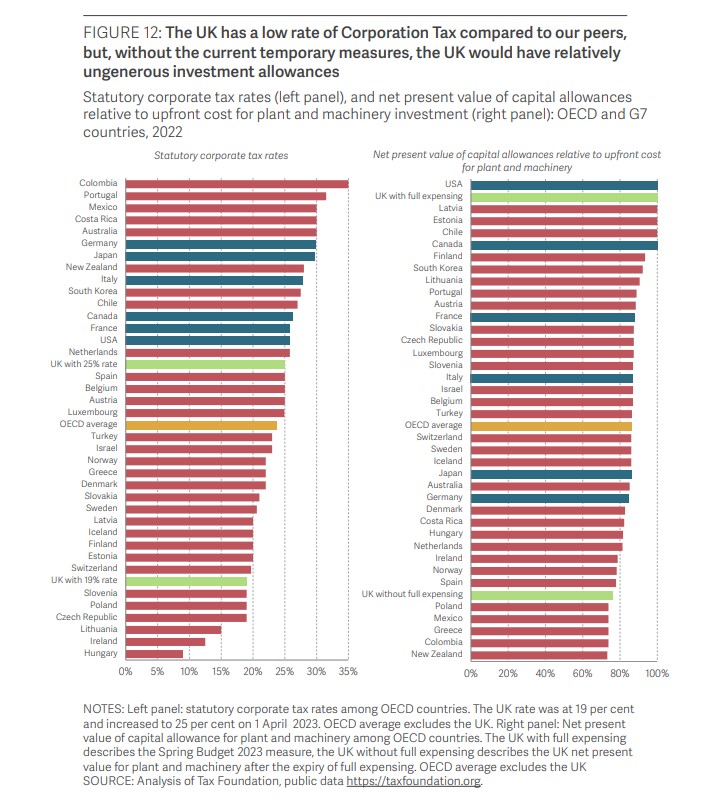

And thanks to the full expensing policy, Britain has one of the most investment friendly corporate tax codes in the world. We currently sit joint top, but before Sunak brought in the super-deduction, Britain ranked 34th out of 39 OECD countries for what’s known as ‘capital cost recovery’. In 2026 when full expensing expires, the UK’s will plummet down the international tax competitiveness rankings once again.

.

A ‘use or lose it’ time limited sale might be a great way for DFS to shift some sofas, but it is a terrible way to get business to make multi-million pound investments. And we really need them to make those investments – every year, bar three, for the past three decades, Britain has been in the bottom 10% of the OECD for investment (new equipment and machinery).

The key problem with the DFS approach to tax policy is that businesses do not consider each investment in isolation. Rather they look at how they fit into investment cycles that last the best part of a decade. Businesses won’t respond to a temporary tax break at the start of an investment cycle if they aren’t confident that the follow-on investments in year five, six and seven will benefit from the same relief.

And businesses want to know that if a machine breaks down early, they can replace it without incurring a larger tax liability.

The news that Jeremy Hunt is planning to extend the £10bn tax reform to the end of the next Parliament should be welcomed then. Yet there’s no good reason why he shouldn’t go further and make it permanent.

The main blocker to making it permanent will be how it affects Hunt’s fiscal rule. Hunt has committed to debt as a share of GDP falling by the fifth year of the OBR forecast. It isn’t a bad rule in principle, yet it does bias against policies like full expensing which front load their costs.

As the Resolution Foundation points out, full expensing’s long run cost is likely to be much lower than the £10bn or so, the OBR score it. First, some of the increase comes from firms bringing forward future investments. Second, the annual cost will decline as yearly depreciation allowances exit the system. Third, and most importantly, the cost will be offset by higher GDP growth as businesses become more productive thanks to all the new investment.

In fact, the Resolution Foundation estimates that the growth boost could be big enough to raise tax revenues in the long run.

After last year’s bond market chaos it is understandable that Hunt doesn’t want to deviate from his fiscal rules, yet there’s no benefit to sticking to a fiscal rule if it rules out a policy that will cut debt in the long term.

In the Autumn Statement, Jeremy Hunt has an opportunity to end the DFS approach to tax policy and give businesses the confidence (and the incentive) to invest in the long term. Let’s hope he takes it.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.