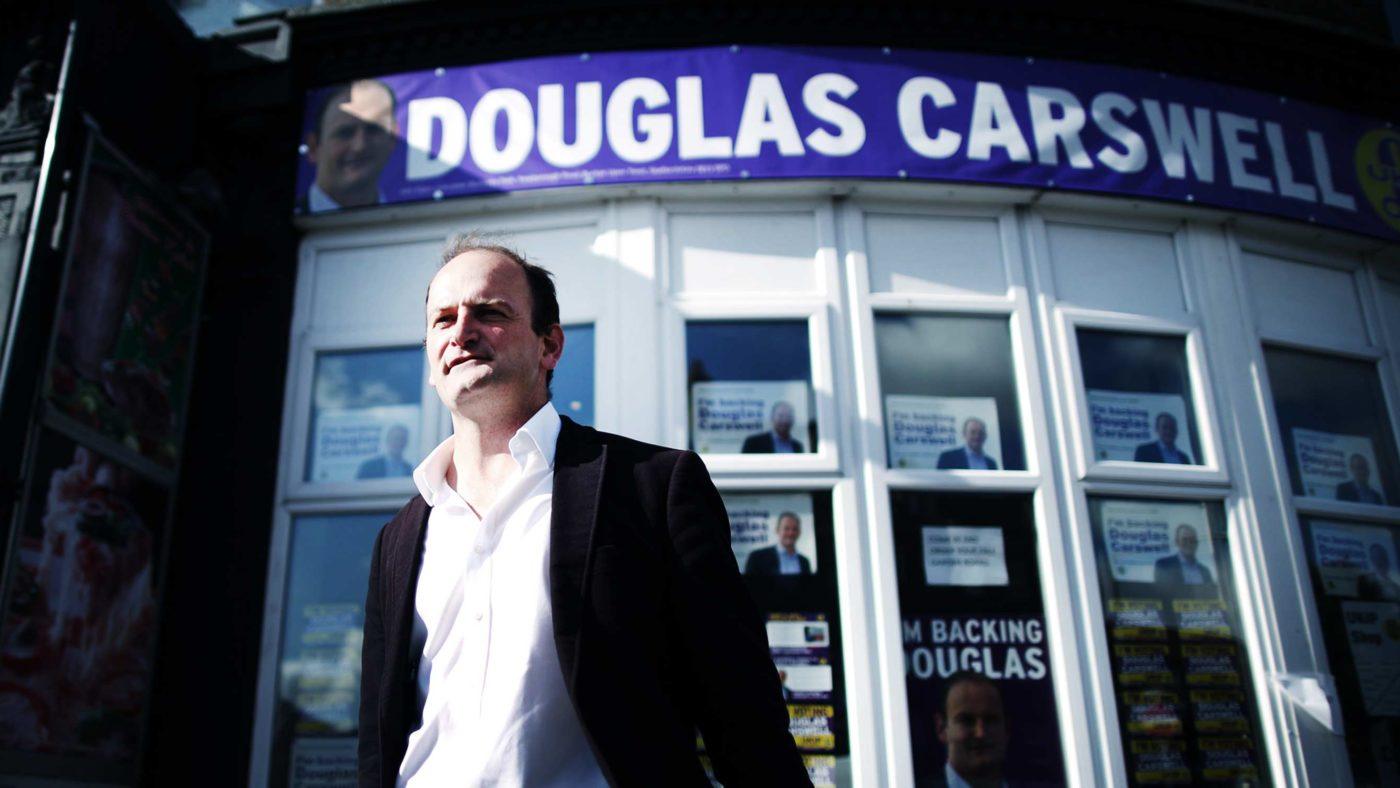

The squabbling between Douglas Carswell and Nigel Farage – over the EU referendum and much else besides – has been one of Westminster’s most riveting dramas in recent years.

But it was not just his defection to Ukip (and recent abandonment of the party) that marked the MP for Clacton out as one of the most interesting men in British politics. I first came across him when I worked with him and Daniel Hannan on their localist think tank, Direct Democracy. Since then, he’s always been genuinely unafraid to think the unthinkable, at least within the context of Westminster’s clubby circles.

His new book, for example, argues that British politics is in need of revolution – that free-market liberals need to fight to preserve our open system from parasitic, oligarchic elites and irate, pitchfork-wielding populists alike. That’s why its title, ‘Rebel’, is both a description and an instruction.

We spoke at CapX’s offices about Brexit, Lucretius and why he thinks Ukip is now the equivalent of the Anti-Corn Law League. This is an edited and abridged version of our conversation.

Robert Colvile: So, how are you feeling?

Douglas Carswell: I’m feeling extraordinarily happy. I’ve not felt this cheerful and relaxed for a long, long time.

RC: Is that because of leaving the European Union, or leaving UKIP?

DC: All of it. Politics is a funny thing. When I first stood to be selected as the Tory candidate in Harwich & Clacton, as it was then, I said: “If you select me, be clear you’re selecting a candidate who will do everything he can to force a referendum and campaign for us to leave the European Union.”

I said as much in my maiden speech. Any time anyone stuck a microphone anywhere near my chin, I said we should leave the European Union. I changed parties and triggered a by-election to achieve it. Then when Theresa May, fabulously, actually pushed the button with Article 50 I said, “Job done” and everyone went, “What did you mean by that?”

RC: That actually touches on the book, because one of the things you say is that everyone is more interested in the game of it than the actual ideas…

DC: Yes. The Lobby are terribly nice people individually, but as a pack they’re simply awful, because they focus on the soap opera of politics.

You’ll have a Budget published which will have serious implications for millions of people, yet it will all be reported through the prism of what it means for George’s career. I long since came to realise that a certain kind of journalist will report what I do or don’t do in the context of what it means in terms of Douglas’ relationship with Nigel and Nigel’s relationship with Douglas. Frankly, all that stuff is totally irrelevant.

RC: When you re-defected, everyone said…

DC: Defection is a pejorative term. I got permission from the electorate. I got permission to switch parties.

RC: You got it once. Don’t you need to get it again?

DC: Oh, I’m not changing parties. You’ll understand this from our days in Direct Democracy. If you campaign for recall, as I do, that is to strengthen the part of the voters vis-à-vis the party bosses. Imagine a scenario where the frontbench could withdraw the whip and trigger a by-election for any of their MPs. It would make it impossible for people like Nicky Morgan to force Theresa May to rethink education policy or Peter Bone to do the same with tax policy.

But I do think you should have a convention, which I like to think I helped re-establish, that if you switch from Party A to Party B then you should have a by-election. It’s a subtle but fairly profound difference.

RC: Is it a distinction your constituents have grasped?

DC: I sent out an email to over 20,000 people. I think I had 26 negative responses. Literally 26 out of more than 20,000. The reaction’s been overwhelmingly positive. A lot of “Glad you did it”, “We made that move some time ago” or “Why didn’t you do it sooner?”

I think a lot of people… I think I was partly reflecting local opinion rather than necessarily leading it. A lot of them switched to Ukip because they wanted to leave the European Union. They don’t really want to stick with it. It’s a bit like campaigning on a platform for the anti-Corn Law League. It’s done and dusted.

RC: On that point, I was interested that everyone said “He’s eventually going to rejoin the Tories.” Having read this book, it feels like it would be very hard for you to join any political party.

DC: This is what I find so baffling. The book makes it fairly clear that I’m pretty unconservative. It’s actually quite a powerful critique of patrician Toryism.

RC: So what’s the basic thesis?

DC: That politics is never been more unpredictable than it is today. We’re seeing the rise of new radical parties and movements right across the West. This is happening in the Netherlands, it’s happening in Sweden, it’s happening in California, it’s happening in Clacton.

What accounts for this? If you listen to the political establishment and the pundits they’ll all say, in a very condescending way, “It’s globalisation.” But if it was economic distress that was driving the rise of these New Radicals, you would expect those most economically distressed to be at the forefront of it. On the contrary, there’s good evidence that the average Trump supporter in the primaries had an income significantly above the US average.

So, yes, there is inequality and incomes have flatlined amongst unskilled workers. But the cost of living for many has fallen, meaning living standards have risen. And in fact, there’s good evidence to suggest there’s less income inequality in Britain today than there was 10 years ago.

The real inequality is an inequality between income wealth and asset wealth. If you happen to own a hedge fund or a house, you’ve done relatively rather well. If you rely on an income, you’ve done relatively badly. The driver is that there’s an economic oligarchy that has used monetary policy and created regulatory frameworks that allow a small elite to do incredibly well.

RC: So you’re saying the problem’s not the guys with the pitchforks. It’s the guys barricading the gates.

DC: Yeah. It’s the Romanovs who caused the Russian Revolution. It’s the Bourbons who caused the French Revolution. It’s George the Third who triggered the American Revolution. What we need to do is make sure that the insurgency against the oligarchy is more George Washington than Lenin, that it’s more John Locke than Robespierre…

RC: More Douglas Carswell than Nigel Farage?

DC: Well, actually, I think it’s a great compliment to the political culture in Britain that our version of the New Radicalism is actually relatively liberal, in the English sense. I’m been proud to have been a member of UKIP. I wouldn’t feel the same about Geert Wilders’ party if I was a Dutchman or Marine Le Pen if I was French. In fact, I would be even queasy about having voted for the Republican candidate in the last presidential election.

RC: What’s most striking about ‘Rebel’ is that this is not your usual political book. Your bibliography, for example, is an astonishingly diverse collection – Piketty, Fukuyama, Stefan Zweig, Mervyn King…

DC: The most important I think is Lucretius’s ‘On The Nature of Things’.

RC: I was going to say Matt Ridley.

DC: Well, Matt introduced me to Lucretius.

RC: I don’t think that’s what people are expecting when they pick up this book. They’re expecting stuff about Ukip. They’re not expecting 200 pages of the Roman Republic, the Venetian Republic, the Dutch Republic.

DC: It is mainly a history book. It is an attempt to attack this philosophical claim that elites are able to order the world by design. I’ve gone back several centuries to do that.

In the Roman Republic, the Venetian Republic, the Dutch Republic, you have a dispersal of power that allows innovation and free exchange, which means you get an extraordinary increase in per capita GDP. In the Roman Republic the level of per capita GDP wasn’t surpassed again until the 17th century. Without question, the Roman system becomes a sort of predatory extortion machine. But in the early days it was extraordinarily free market-based. By the beginning of the first century BC, over a period of 300 years, Rome had achieved a quadrupling in the population and a doubling in the per capita income of that population. That doesn’t happen anywhere else.

RC: But then, you argue, the parasites fight back.

DC: Yes – the problem is you get a sudden inflow of new wealth from somewhere. In Rome, Venice and Holland it was the acquisition of provinces that allowed a small elite to syphon off a huge amount of wealth and establish an oligarchy. Then you get a backlash to that, but the anti-oligarch insurgents are always so inept that they basically allow the oligarchy to gain even more power.

Today, the new inflow of wealth is not from captured provinces, but from posterity. Since the 1970s, the bond market has allowed governments to live beyond their means and to basically take wealth from tomorrow to spend today. This sudden inflow of wealth is creating this oligarchy.

And the reaction to it is playing straight into their hands. Again and again, the anti-oligarch radicals are talking in terms of redistribution and restrictions on free exchange. The response from the Left in this country to quantitative easing is to call for “people’s quantitative easing”. We need to challenge the oligarchy, but in a way that allows globalisation and specialisation, exchange and the free market, to survive.

RC: Your diagnosis I think is a very good one. But I find it really very hard to imagine how you convert this into a political programme. You cite the example of Vote Leave, but they had really clear, popular messages. I don’t think “abolish fractional reserve banking” is the kind of slogan you can really sell…

DC: But these things don’t happen in a vacuum. The reason why those messages worked is because 20 years ago people like Dan Hannan started to create a compelling intellectual critique of Britain’s EU membership.

RC: What I’m wondering is how this gets to that.

DC: I think there is actually a programme in there, and that events will make it a much easier sell. I start by talking about reform of monetary policy and the banking system. Now both of those things seem pretty obscure at the moment. As indeed the Brussels machinery and the idea of the acquis communautaire must have once seemed.

The idea of taking back control, ultimately, could only flow once people had come to understand – whether they realised it or not – what the acquis communautaire was all about. And I think people will begin to realise that the banking system is rigged. It’s not just the Libor scandal, but the entire way in which our currency is run is designed to devalue the worth of currency. We’ve managed to do in 40 years what the Romans took two centuries to do.

When a whole generation of people below the age of 30 are unable to buy a house because successive governments have hosed cheap credit at the market, when we start to realise that central bankers are the economic bad guys and that have been the most important driver in economic inequality in this country – I suspect people will start to demand far-reaching change.

Certainly I suspect that the current shape of the Bank of England is not going to survive for much longer. It’s about to enter the firing line politically whether it realises it or not.

RC: But won’t they demand the pitchforks kind of change, as opposed to yours?

DC: Well, they will if people like you and me sit quietly. If you and me and others like us who are free-market classical liberals don’t argue the case for change. I think you’ll end up with the Corbynistas and their Paul Mason faction coming along and demanding intervention to tackle the symptoms of the oligarchy.

The book is arguing that this is decision time. If you want to preserve the liberal order, you need to start recognising that the economic and political position that we’re in is intolerable.

RC: Which is a rather more gloom-laden message than your previous books. It feels like they were a lot more optimistic.

DC: I think the Brexit referendum had quite a big impact on me, because it destroyed what last vestiges of respect I had for elite opinion-formers and pundits and all those behind Project Fear. It was the moment when the curtain is drawn back and you realise that the wizard of Oz is just a befuddled middle-aged man who hasn’t got a clue.

RC: There’s a very inspiring section, especially for CapX readers – five or six pages where you go through all of the statistics about how life is getting better thanks to the market.

DC: You see? I am optimistic.

RC: But isn’t there an argument to say: in that case, why mess with success? That the kind of upheaval you’re suggesting – yes, it could lead us to the sunlit uplands, but it could also go horribly wrong…

DC: If you’d been living in Rome at the end of the first century BC or Venice in 1200 or the Dutch Republic in 1650 it would be very, very easy to believe that you were living in a world of permanent progress and the pinnacle of human achievement. What we need to do today is to make sure that we’re not at the pinnacle of another golden age.

If people go protectionist, if people go state interventionist, if people begin to demand the sort of redistribution that every anti-oligarch insurgent seems to have demanded, we will destroy the secret of … I was going to say Western success. It’s actually become a global phenomenon now.

France is a microcosm of where the West is heading if we don’t act. French politics is a choice between a fascist, a technocrat, and a crook. If we don’t clean up capitalism and disperse power again and think seriously about how to deal with the political and economic oligarchy – if we don’t respond to the emergence of that oligarchy with a radical liberal agenda, people will respond to it with a redistributive, populist, statist agenda that really will mean that there can be no winners.

RC: And why stay in the House of Commons? You make it quite clear that you think 90 per cent of the people there are wasting their time.

DC: My view of politics is basically quite cynical. I think most politicians are decent people. But most of them end up being like actors. They want to be on the silver screen, but they don’t really care too much about the script. If there’s a referendum and Leave wins, they pivot effortlessly to accept the new script. And may I say they’re reading from it quite beautifully.

The trick is to not really give a damn about which one of the 650 members occupies which position as a minister. The key is to make sure that you create a climate, as Friedman once said, in which even the wrong people have to do the right thing.

So why do I stay in the House of Commons? Well, first and foremost, because the people in Clacton elected me to. And I hope I can use my position to try and help present a script that means that even the wrong people have to do the right thing. Today, even the former ministers in David Cameron’s Cabinet have to talk about the triumph that is Brexit and the optimistic future outside the EU. I’m delighted by that.

RC: And presumably by Brexit…

DC: I think Brexit has reminded the PPE-studying elite whose country this is. There’s a bit of humility amongst the governing classes. I think that’s a profoundly good thing. I think it means that they’re going to be much more open to some of these changes. There’s going to be this great flowering of new thinking. We’re starting to see the signs of it. Ostensibly it’s got nothing to do with Brexit – but once the façade that the elite has got everything under control crumbles, change in a whole bunch of other areas becomes possible.

To give just one example, digital changes the whole context in which the citizen sees their position vis-à-vis the governing classes. It sounds trite, but if you go home in the evening and you and your family decide what you watch on Netflix, you start to resent the fact that you can’t go online and book a GP appointment for nine o’clock the next day.

Why do you have to engage with state provided services on the state’s terms? Instead of a nationalised curriculum, you could have a personal curriculum. Instead of just a generic NHS, you could have an NHS that actually means a healthcare programme for every family.

I think a whole world of change expectations are coming. Brexit is key because it marks the end of a smug orthodoxy in not just European policy, but a whole host of things.

RC: Well, thank you very much.

DC: I’m afraid I was rather jumping all over the place in my answers.

RC: No, it was my questions.

DC: I haven’t had enough coffee. That’s probably the problem.

Douglas Carswell’s book ‘Rebel’ is out now from Head of Zeus. You can buy a copy here.