The ONS published its preliminary estimate for GDP growth in the first three months of 2018. This found that growth that quarter was a stuttering 0.1 per cent.

The figure is slower than the already-modest 0.4 per cent growth seen in the last three months of 2017. The difference between the two is easy to account for. Construction output fell by 3.3 per cent. Compared with the same three months a year earlier, growth in non-construction GDP was actually faster in the January to March 2018 period than it was in October to December.

Construction is quite volatile from quarter to quarter, and construction not done in one quarter tends to be caught up later. There’s a pretty good chance that will happen this time as well, with construction adding 0.2 or 0.3 percentage point to growth in the period to June or to September. I’d guess that we’ll see about 0.6-0.7 per cent growth for one of those three-month periods.

Some have claimed that the drop in construction was down to the snow in late February and March. The ONS didn’t altogether reject this theory, saying there was some evidence of a snow effect. But it did point out that construction was down right across the quarter, including in periods when there wasn’t snow.

This is only the preliminary assessment, and there must be a fair chance the ONS will revise its view of the impact of snow. For instance, the National House Building Council claims that 30 days of housebuilding construction were lost due to the snow.

Setting aside construction, growth in the rest of the economy is in that fair-to-modest state that it’s been in since the start of 2017. We should probably still expect growth for the full year to be somewhere between 1.5 and 2 per cent, broadly as expected.

Currency markets interpreted the GDP data as undermining the case for an interest rate rise in May, with sterling losing ground against the dollar immediately after the data were released. That could be correct.

The Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee found every excuse going not to raise rates for nearly nine years until late 2017.

Recently, the Bank doesn’t even seem to know whether it thinks that slower growth tells us we should raise rates (because they interpret it as meaning the underlying potential for growth is less, so inflation is more of a threat), or that slower growth tells us we should not raise rates (if they interpret it as meaning the economy is under-performing).

What they seemed to care most about was evidence of pay starting to rise in real terms.

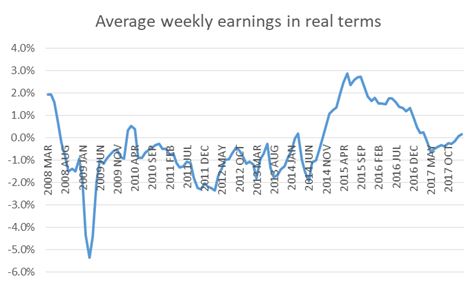

They’ve got that in recent months. The above chart looks at average weekly earnings relative to inflation. We can see that, after a brief period of stagnation to modest contraction in 2017, real wages are now growing again. If inflation falls back further, real wage growth will continue to rise.

(Incidentally, there seems to be a peculiar reluctance amongst commentators to use ONS’s preferred inflation measure, CPIH. Most headlines still appear to quote CPI, the Bank of England’s policy target, as if it were the inflation rate. It is not. It is a policy target, long known to be imperfect as a measure of inflation because of the absence of housing costs — which are now included in the CPIH. The ONS says it’s best. We should use it.)

My guess is that the May interest rate decision will be heavily split, probably 5-4 or 6-3. It could yet go either way but I think the Bank probably won’t be put off by one quarter of weak construction stats. And if it were, rates would rise the following quarter instead.

The economy is by no means going gangbusters. But it is solid. The budget deficit is largely eliminated (indeed we are now running a surplus on current expenditure for the first time since the days of Gordon Brown). Unemployment is at its lowest level for over 40 years. Inflation is well under control. Sterling has picked up a bit. Financial markets are steady.

It’s one dodgy quarter. We’ll get over it.