Plaid Cymru have a new leader and he’s been committing news, from demanding a focus again on independence, to demanding an end to Brexit. But as neither of those are going to happen, let’s look instead at one of their particular bugbears: the Welsh language.

I grew up on the border between north-east Wales and the north-west of England. It’s weird to come from a place that no-one really knows and which is stuck between identities that it is stereotyped by but to which it does not conform. Not Welsh enough for Wales, not English enough for England.

It’s not an area that votes for Plaid and there’s a reason for that. The party is too closely associated with being a single issue campaign on language. It colours everything they do, and for as long as it creeps into every policy area they will struggle to convince voters to turn out and vote for them. I think part of the party’s problem is it is too wedded to social engineering – something Plaid have manifestly failed at when it comes to increasing the number of Welsh speakers.

But, instead of being able to see that, they’re too happy believing statistic after statistic that Welsh is on the up, and that state subsidy is helping. These language statistics are used to divide us from those that live just a stone’s throw away. The people that we’re often related to, work with, are most likely to live with and be friends with. And I think that all of this has hindered real debate on whether subsidy and public intervention is worthwhile or needed.

One of the most obvious, for me at least, is the way that official stats on Welsh language regularly overstate its use. The figures are always so high. Much higher than you’d expect. This was very clear this week when the Office for National Statistics issued an update to its language survey suggesting a rise from 726,600 speakers of Welsh in June 2008 (or 25.8 per cent of the population) to 874,700 in 2018 (or 29.3 per cent of the population).

This figure is bunkum. A third of Wales does not speak Welsh.

Officials that stick to that figure and use it to bury their head in the sand or justify calls for more public spending on Welsh language institutions are either a) failing to understand their own figures, or b) deliberately misleading the public.

There has not been an increase in the number of speakers in the past decade. Certainly not an extra 4.5 per cent. In fact, there’s been a decline.

But Matthew, the ONS has done a survey, it’s been responded to by ordinary people and their figures have to be taken seriously, right?

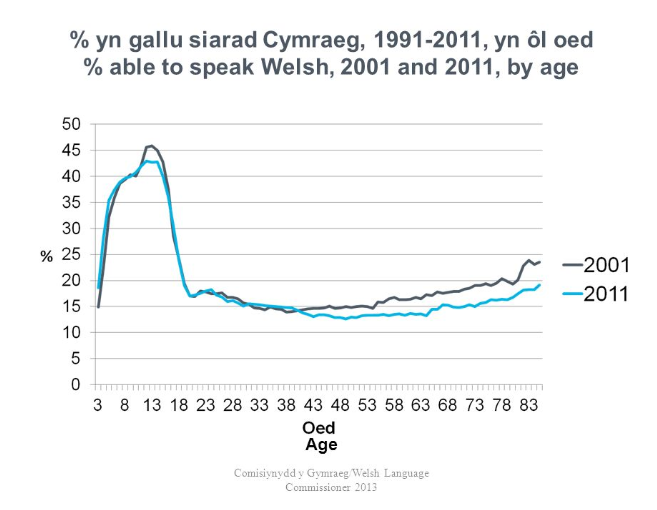

No. Language stats are filled in by adults and by parents, but include statistics on childhood proficiency of language. The best way to illustrate how useless this is as a way of measuring Welsh language proficiency is by showing you one of my favourite graphs from the Welsh Language Commissioner.

Parents are asked whether their kids, having spent years at school learning a subject, are any good at it. Unsurprisingly parents are pretty accurate with their own ability to speak the language, but heavily overestimate the ability of their kids.

How do we know that’s true? Well we know from when people start self-reporting (age 18) we see that huge drop off. And we also know what language children speak at home and what language adults use on websites, with the council and courts.

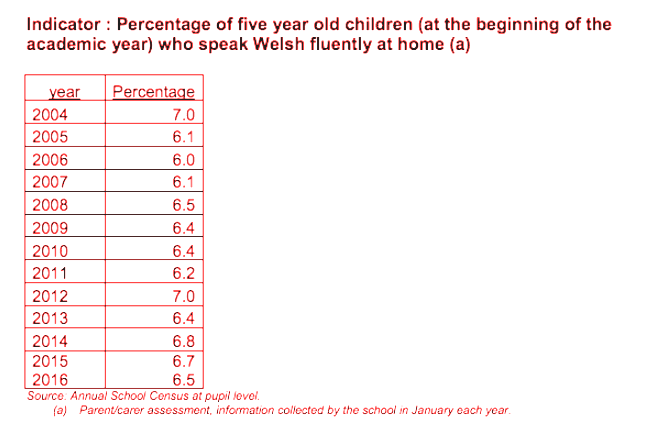

The honest percetnage of those who speak Welsh as a first language at home is 6.5 per cent, although the number increases as more go to Welsh language medium schools. Even then fluency isn’t guaranteed, nor natural language use, nor social language use.

So it’s about 6.5 per cent of children that speak it as a first language, and it’s about 7.7 per cent of the population at large. Much lower than the census figure and much, much lower than the ONS population survey.

Fair enough, parents think their little darlings are wonderful and perfect in every way – and are wrong. Shock. Not a big deal?

But it is a big deal because it then feeds into a whole host of misleading stats about demand for the language, and for demands on funding.

But even language spoken, spoken at home and fluently, is not the same as the language you want to use to speak to other people, institutions or government. When people go to the doctor, to the bank or fill in government forms, they have differing use of services provided in Welsh. Fluency does not equal preference. And preference is currently far smaller than fluency despite the money thrown at it by campaigners and government.

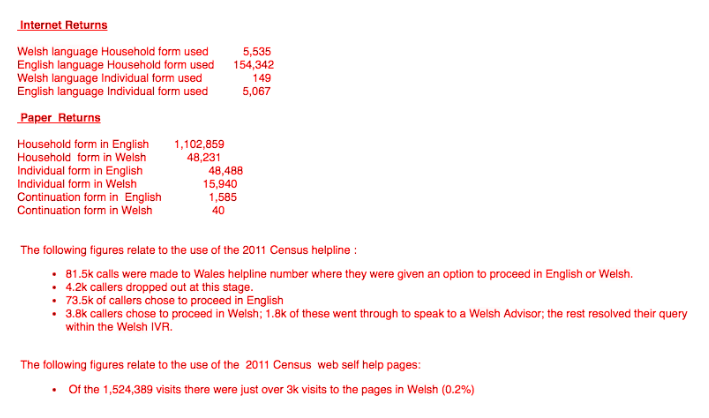

Let’s take the census. A government form, fully available in both languages and delivered to all homes. Completed either online or on paper. Calls made to the Census helpline were bilingual with the Welsh language option offered first. Every effort made to allow people to choose the language of their preference and overcome the bias of the fact English is used in just about every form of daily life in Wales. Just 3.4 per cent of family forms online were completed in Welsh, and just 2.9 per cent of individual forms.

Paper copies fared little better for households at 4.1 per cent, but individual forms were substantially higher with a whole quarter filing their copy in Welsh. That last one is intriguing, but as they’re requested it’s not unusual for political statements to be made via census forms, and with old people’s homes and university halls having many individual forms you’d expect higher than average returns in Welsh. All told it was 5.05 per cent that answered in Welsh.

But the preference of language becomes even more obvious when you look at other services. Just 0.08 per cent of driving theory tests were taken in Welsh and just 0.45 per cent of practicals. 0.6 per cent of phone calls to NHS Direct and just 0.1 per cent of website visits to it.

Stats on bank ATM use in Welsh (which throughout Wales regularly put a language option after the card is inserted) are not available, but I was told by one reputable and large high street bank that it was less than 0.1 per cent.

Why does this matter though? What’s wrong if statistics are inflated? What’s wrong if the government wants to lie to say it’s succeeded in a social engineering goal?

Well, it matters because it informs debate, it matters because of the sheer amount of money and time and effort that goes into Welsh language. It matters, in short, because of public subsidy and public regulation.

If you want a job with Gywnedd council you need to speak Welsh (all new jobs advertised require it), if you want to work in Snowdonia National Park you need to speak the language (again all jobs, everything from rangers to kitchen staff required it). Not to mention Welsh language only positions in the civil service, at the Assembly, and of course at publicly funded Radio Cymru and S4C.

Across Wales the average pupil at a Welsh language school receives £341 more than at an English language secondary school. Councils spend millions of pounds and hundreds of man hours translating every document produced, at ensuring there is always provision for services that are not then used, and employing staff that are strongly over-representative of the language balance in the country.

I get that language is emotive, it is at the heart of the identity politics debate in the country. But the debate always focuses on the heat and fury of campaigning groups. When Newsnight hosted a debate on spending on the language, social media descended into hyperbole and vitriol at author and columnist Julian Ruck. He’d had the temerity to suggest that extra spending and spending wasn’t achieving the goal of getting more people to speak the language. I know, unforgivable.

But millions of us make individual choices on language every day that don’t conform. Yes, there were historical government boundaries to language use. I’m well aware of this – you don’t have a name like Kilcoyne and not know language history. But the removal of these restrictions does not give license to impose new ones or new costs on others. The ‘undoing historical wrongs’ argument is bizarre. This tries to remake the world according to one person’s vision of how it should be, rather than working with the world as it is.

As Kristian Nietmietz wrote recently for the Telegraph, most people find that learning a second language when they don’t have to is a waste of time. Language is, at the risk of being tautologous, used for communication: not for “feel good” reasons. Welsh people are no exception, we use the one that’s most useful. When not obliged to use Welsh by government subsidy or regulation, we’re overwhelmingly choosing to speak English.

As a native English speaker, along with around 93 per cent of my fellow Welshmen, here’s a bit of advice for new Plaid Cymru leader Adam Price. If you want to reach voters that aren’t members of Cymdeithas yr Iaith or who don’t hark back to the glory days when Owain Glyndwr led a rabble on a rout, you might want to ditch the obsession with the language and with independence. At least Brexit is a live topic, even if it is one that a majority of the Welsh are not with you on.

Instead focus on the areas that are really quite exciting. Your support for a 3 per cent land value tax is wildly off kilter, but at least you’re showing that you’re thinking about the idea and the issue. We’re here to help if you want to come up with a figure that would work for Wales.

And Adam, your support for a cut in income tax (11p basic rate, and 31p higher rate) could really set the political agenda of Wales alight! Give Welsh people more power over the pound in their pockets, trust them to make the choices they think are right for them and their families, and they may just trust you with their vote.

Importantly, of course, these are policies that would impact the many in Wales, not just the 7 per cent. People will engage with them, not because of a historical grievance, but because they’d be a positive change in people’s lives.