It’s no longer news that voting intention polls have exhibited some dramatic moves lately. Although they have calmed down somewhat in terms of volatility, they remain at extreme levels, with two polls in the last week putting the top four parties within three points of each other, something that had never previously happened.

Polling always comes with caveats, but the current environment adds a new one. If we knew the popular vote shares with certainty, we would normally have a fairly good idea of how they might be expected to translate into seats.

The traditional method of uniform national swing – that is to assume that the changes in vote shares since the previous election in each constituency match the changes in the vote share nationally – works if the swings are relatively uniform.

In fact, they don’t normally even need to be uniform, as long as the swing in Labour-Conservative marginals matches that in the national popular vote, and that other parties have vote shares that are both low and thinly-spread.

Right now the changes in the Tory and Labour vote shares are so large (some polls have them both down 20 points on 2017) that a uniform swing is arithmetically impossible, since in some cases one of them has fewer votes than that to start with. Additionally, the Lib Dems and Brexit Party vote shares are now at similar levels to the traditional main two.

The modern solution is to model constituency vote shares using multilevel regression and poststratification (MRP), an effective but very expensive technique. Otherwise, we need to make assumptions about how votes would be distributed.

Now, to be clear, anyone saying that a given set of vote shares would produce a particular set of seat totals based on a set of assumptions is speaking with much greater certainty than is justified by the rather limited evidence. As such, what follows should be treated as illustrative rather than a projection.

Last month’s European Parliament elections saw some huge swings from any result seen previously. The swings were in most cases also much bigger than current Westminster polling suggests.

On the basis that current polls for most parties sit somewhere between the results of the 2017 general election and the European elections, one way to account for the realignment is to interpolate between the two sets of results in national vote shares, and also in each constituency.

In other words, the assumption is that more the Tory or Labour votes fall or the Lib Dem and Brexit Party votes rise compared with 2017, the more the distribution of that party’s vote resembles that in the European elections.

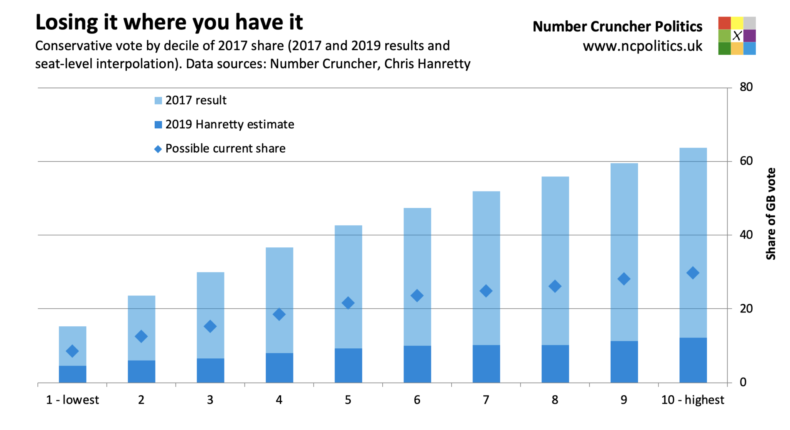

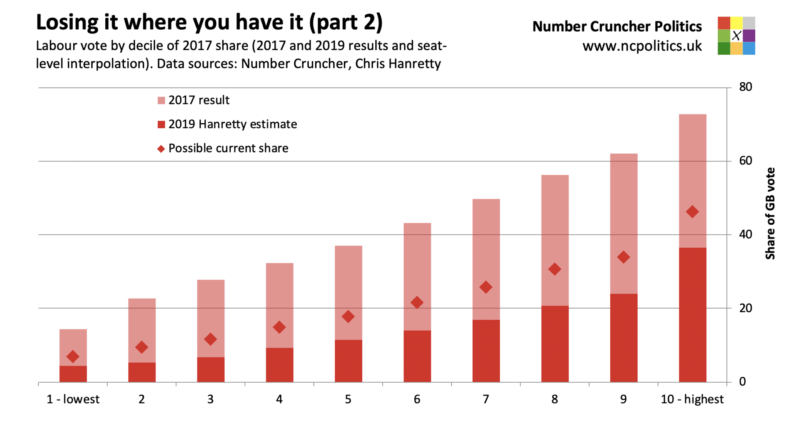

Those results were declared by council area rather than constituency, but thanks to Chris Hanretty’s modelling, we have good estimates of how each seat voted. The following charts compare the two results by deciles of general election support:

To be sure, many people vote differently in the two sets of elections, not just in terms of the levels of support (which is obvious) but also its shape. But to the extent that the European election results and the dramatic moves in recent Westminster polling have a common underlying driver – a sizeable number of people on both sides of the Brexit debate wanting to express a view on it – last month’s result is likely to give us a better steer than guessing or making unsafe assumptions.

If people were assuming that having parties on low vote shares invariably means a parliament that’s not just hung, but hung, drawn and quartered, then I have a big warning.

Yes, on current vote shares, no party would be anywhere near an overall majority. If we put all four main parties on 21 per cent, the assumptions detailed above would put Labour on around 180 seats, the Brexit Party on around 160 seats, the Lib Dems on roughly 130, the Conservatives down to about 100 and the SNP in the 50s.

Note that this does not take account of the strength of each party’s ground game, which is likeliest to hurt the Brexit Party, or tactical voting. Relatively few people vote tactically, although for all the reasons already given, a small number might make a material difference.

But it wouldn’t take an absurd swing from here to produce a majority. Any one of these parties could win 326 seats with a lead of about 10 points (and a vote share of around 30 per cent) if the other three split the rest of the vote as evenly as they do at the moment.

How could the Brexit Party and Lib Dems do so well in this example under first past the post? The answer is that having an evenly-spread vote is a liability when your vote is low and the Conservative and Labour vote shares are high. But there comes a point at which it becomes an advantage – instead of narrowly losing in lots of seats, you start up narrowly winning lots of them.

Running this exercise the other direction, dropping too far into the teens could see Labour or Tories being decimated, with seat numbers dropping into the double digits. Labour would have a degree of protection, because its enormous majorities in its safest seats would save it in many cases. But the Tories really would be staring into the abyss.

The thing about first past the post is that it can produce some very extreme results if you put the right numbers in. To repeat my earlier caveat, this is an illustration of things that are possible, rather than likeliest outcomes. In particular, it is far from clear how party vote shares would actually move in relation to one another.

The traditional advantage the Tories and Labour enjoy under our electoral system has always depended on their support being substantially higher than other parties, and efficiently distributed. This advantage is being eroded by each now suffering an outsize loss of support in areas where they have it.

As things stand, the red-blue postwar duopoly is under serious threat.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.