Why did the Industrial Revolution start in Northwestern Europe? Why did the West industrialise so much earlier than the rest of the world?

Most economists would argue that this happened because the West developed a set of institutions that were uniquely conducive to economic growth, especially the rule of law, secure property rights, impartial and effective legal systems, and freedom of contract. This is, of course, a very general and broad-brush explanation, which still leaves plenty of room for disagreement, for example about the role of cultural factors, geography, external trigger events, or specific economic policies. But it is the smallest-common-denominator explanation.

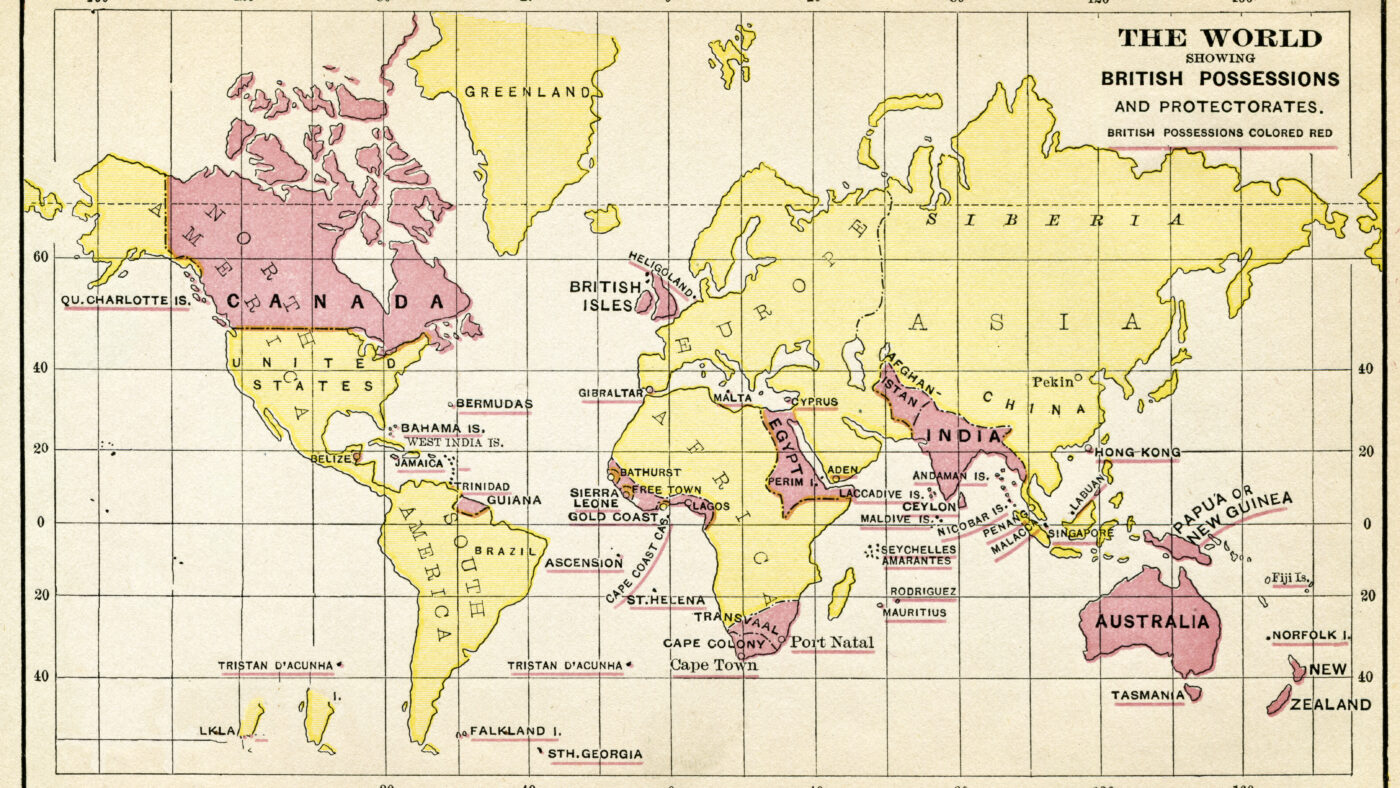

The more fashionable explanation, though, is that the West grew rich on the basis of colonial plunder and exploitation.

As is often the case, the fashionable view is best expressed by Owen Jones in the Guardian:

‘Capitalism was built on the bodies of millions from the very start. […] The capital accumulated from slavery […] drove the industrial revolution […]

[T]he blood money of colonialism enriched western capitalism. […]

The west is built on wealth stolen from the subjugated, at immense human cost.’

This is not a new idea. But it has experienced a revival over the past couple of years, in the wake of the ‘Great Awokening’. It was, for example, the sentiment behind the toppling of the Colston statue in Bristol in 2020, as one of the organisers later explained:

‘[S]o much of the prosperity enjoyed today in the UK […] comes off the back of historical atrocities.’

It is also echoed by Zarah Sultana, the MP for Coventry South (who, because of her trendy anti-capitalist views, is also quite the social media superstar):

‘The wealth that enriched the British Empire and established it as a global superpower meant the murder, destruction, and brutalisation of people across the world.’

One can see why this idea has taken off again: it sits at the intersection of two of the most voguish ideologies of our time, namely, woke progressivism and anti-capitalism. It is a story about white people – white men, mostly – oppressing non-white people, which also doubles up as an ‘original sin’ story of capitalism.

But is it actually true that imperialism makes countries richer? Does imperialism make economic sense?

This question was already hotly debated at the heyday of imperialism. Adam Smith believed that the British Empire would not pass a cost-benefit test:

‘The pretended purpose of it was to encourage the manufactures, and to increase the commerce of Great Britain. But its real effect has been to raise the rate of mercantile profit, and to enable our merchants to turn into a branch of trade, of which the returns are more slow and distant than those of the greater part of other trades, a greater proportion of their capital than they otherwise would have done […]

Great Britain derives nothing but loss from the dominion which she assumes over her colonies’.

He believed that Britain would be better off if it dissolved its Empire:

‘Great Britain would not only be immediately freed from the whole annual expense of the peace establishment of the colonies, but might settle with them such a treaty of commerce as would effectually secure to her a free trade, more advantageous to the great body of the people, though less so to the merchants, than the monopoly which she at present enjoys’.

The liberal free-trade campaigner Richard Cobden agreed:

‘[O]ur naval force, on the West India station […], amounted to 29 vessels, carrying 474 guns, to protect a commerce just exceeding two millions per annum. This is not all. A considerable military force is kept up in those islands […]

Add to which, our civil expenditure, and the charges at the Colonial Office […]; and we find […] that our whole expenditure, in governing and protecting the trade of those islands, exceeds, considerably, the total amount of their imports of our produce and manufactures.’

If imperialism was a loss-making activity – why did Britain and other European colonial empires engage in it for so long?

Smith and Cobden explained it in terms of clientele politics (or public choice economics, as we would say today). Somebody obviously benefited, even if the nation as a whole did not. And the beneficiaries were politically better organised than those who footed the bill.

This proto-public choice case against imperialism was not limited to political liberals. Otto von Bismarck, the Minister President of Prussia and future Chancellor of the German Empire, hated liberals in the Smith-Cobden tradition, but he rejected colonialism in terms that almost make him sound like one of them:

‘The supposed benefits of colonies for the trade and industry of the mother country are, for the most part, illusory. The costs involved in founding, supporting and especially maintaining colonies […] very often exceed the benefits that the mother country derives from them, quite apart from the fact that it is difficult to justify imposing a considerable tax burden on the whole nation for the benefit of individual branches of trade and industry’ [translation mine].’

In his writing about the economics of imperialism, even Michael Parenti, a Marxist-Leninist political scientist (who is, for obvious reasons, popular among Twitter hipsters), sounds almost like a public choice economist:

‘[E]mpires are not losing propositions for everyone. […] [T]he people who reap the benefits are not the same ones who foot the bill. […]

The transnationals monopolize the private returns of empire while carrying little, if any, of the public cost. The expenditures needed […] are paid […] by the taxpayers.

So it was with the British empire in India, the costs of which […] far exceeded what came back into the British treasury. […]

[T]here is nothing irrational about spending three dollars of public money to protect one dollar of private investment – at least not from the perspective of the investors.’

This leads us to a curious situation. Today’s woke progressives disagree with their comrade Parenti on the economics of empire, but they do agree with Britain’s old imperialists, who argued that the Empire was vital for Britain’s prosperity.

So who’s right?

I am in the process of finalising a paper on the economics of empire for the Institute of Economic Affairs, in which I look at historical data on the costs and benefits of imperialism. I don’t think it’s too much of a spoiler when I say that the Smith-Cobden-Bismarck-Parenti side of the argument got it right. Most imperialist projects were, most likely, net loss makers. Imperialism was a folly which the West could afford because they got other things right, but it was a folly all the same.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.