Since I wrote last week’s column, my book “Debunking Utopia – Exposing the Myth of Nordic Socialism” has sailed up as Amazon’s best-selling new book in political philosophy. But why are Americans and others who don’t themselves live in the Nordics buying a book about the short-comings of Nordic-style democratic socialism?

It seems that one important reason is that Nordic countries are used as the main role models for socialist policies by the global left. From Spain to the Baltics, Latin America and the United States, leftist ideologues hedge much of their political beliefs on the success of Nordic social democracy. In the Democrat primary election, the outsider Bernie Sanders very nearly beat the well-established Hillary Clinton to become the party’s nominee for the post of president. His strategy was simple – point to the Nordic countries, and particularly Denmark, as the proof that socialism works.

.@HillaryClinton: “I want to thank @BernieSanders. Bernie, your campaign inspired millions of Americans.” pic.twitter.com/cNWQgelduS

— Fox News (@FoxNews) July 29, 2016

As TIME explains, Sanders was near emotionless when Clinton thanked him for having “inspired millions of Americans” and “put economic and social justice issues front and center where they belong.” Leaked documents show that people in the Democratic National Committee, whose job is to remain neutral, were working against Sanders. The scandal, which has been officially confirmed, suggests that Sanders might have actually won in a fair contest.

But while Nordic-style democratic socialism resonated strongly with Democrat activists in the US, it is far from popular in the Nordic countries themselves. For the last decade, the labor movement and the Social Democratic parties of the Nordics have had a rough time – gradually loosing support and themselves shifting considerably to the right. A quick glance at the Nordic countries confirms this.

Denmark is led by prime minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen, who holds together a coalition of center-right parties. The previous government was led by the Social Democrats, who – I am sure this would shock Democrat activists in the United States if they knew – during their term openly challenged the idea of a generous welfare system, and explained that Denmark needed a new system with more emphasis on individual responsibility.

Finland is also ruled by a center-right coalition. The prime minister is previous businessman Juha Petri Sipilä. Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson, the prime minister of Iceland, is yet again the head of a center-right coalition. Free-market and small-government ideas have become quite popular in Iceland, a country that never fully embraced Nordic-style democratic socialism. Norway is led by conservative party leader Erna Solberg. The massive oil wealth of Norway would make a generous welfare state more feasible than elsewhere. Over time, however, even Norwegians have been alarmed over how working ethics are eroded by a system where much responsibility is placed on the public sector and little on the individual.

Only one of the Nordic countries currently has a social democratic government. That country is Sweden, where the previous center-right government implemented significant tax reductions, opened up public monopolies, and limited the generosity of the welfare state. One might have expected a major leftist backlash to these reforms. However, the Left didn’t come to power in late 2014 because they increased their support (the three parties on the left only gained 0.2 percent more votes than in the previous election), but rather because the anti-immigration party, the Sweden Democrats, took many votes from the center-right parties.

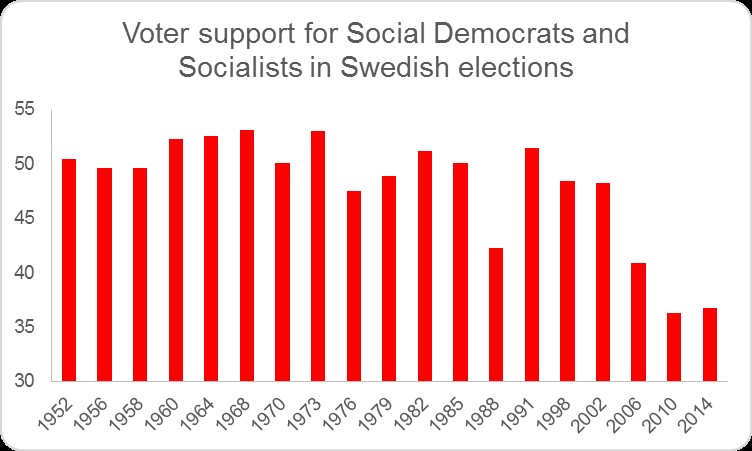

Marco Rubio has joked during a Fox News debate among Republican presidential candidates, “I think Bernie Sanders is a good candidate for president—of Sweden.” While the audience laughed, Swedish royalist remarked that the country has a king and prime minister, no president. More important, the Sanders brand of socialism is not particularly popular these days in Sweden. For much of the twentieth century, the Social Democrats in Sweden were seen as a one-party state, with support from half the population. As shown in the image below, however, voter support for Social Democrats and Socialists has fallen significantly over time.

The political debate in the Nordics is not much different from that in the United States. As I am writing these words, one of the major issues being discussed in Sweden is how high-entry-level wages are creating unemployment. This is similar to the American debate about minimum wages, with the difference being that Sweden doesn’t have any minimum wage legislation. Another urgent topic is how a massive shortage of housing has resulted from rent control and burdensome regulation. A third is how more and more people are relying on sick leave benefits. Sweden doesn’t seem to have a major epidemic going on, but rather a situation where people are increasingly taking advantage of the generous sick leave insurance system.

And lastly, one issue dwarfs all others in the Swedish debate: how can the cost of immigration be curbed and how can the social challenges relating to immigration be dealt with? Many social democrats realize that the fact that Sweden has generous welfare systems makes integration more difficult. Instead of becoming self-reliant, many families who have migrated become trapped in welfare dependency.

As late as 1985 the Social Democrats and their Socialist supporters gained a majority of the votes in Sweden. In the two recent elections they have only received a little more than a third of votes. As of early February 2016, the Social Democrats had never polled so low in modern history. A poll of polls by Swedish magazine Dagens Samhälle shows that merely a third of voters are backing either the Social Democrats or the Socialists. Even with the support Green party, which is careful in not identifying itself as socialist, the Swedish left is far from a majority. Jonas Hinnfors, professor in social sciences, is one among many experts who has commented on the crisis of Swedish Social Democrats. According to Hinnfors, the party suffers from a long-term and deep sense of disorientation.

Sanders, whose message of introducing Nordic-style democratic socialism has rocked the Democrat party in the US, would probably not even be welcome in the Swedish Social Democrats, who are fiscally conservative. His supporters, who strongly believe in the power of socialism and wish to radically expand the scope of the welfare model, would be surprised if they followed the actual debate in Nordic countries. Here, where generous welfare models have become a reality, the enthusiasm for the system is nothing like it is in the US.

While Nordic-style welfare policies certainly do have their advantages, with time they have contributed to various social problems, the main one being a deterioration of responsibility norms and entrapment of families in welfare dependency. While the American left is convinced that Nordic-style welfare policies are the cure for nearly all social ills, the Nordic countries are waking up to the realization that the social success of the region owes more to the unique Nordic culture than welfare policies. Generous welfare policies do little to reduce the social exclusion experienced by many who have an immigrant background.

Nordic-style democratic socialism is simply not living up to the idealized image that is creating enthusiasm amongst Democrat activists in the US. As often in politics, the grass looks greener from a distance.