The lesson from Iowa is that you can fool half the people all of the time. Iowa will always be Iowa. This, remember, is a state whose caucuses have previously been won by Rick Santorum and Mike Huckabee; a state in which the televangelist Pat Robertson once won the support of more than one in four Republican caucus-goers. Its predictive powers are limited, to say the least.

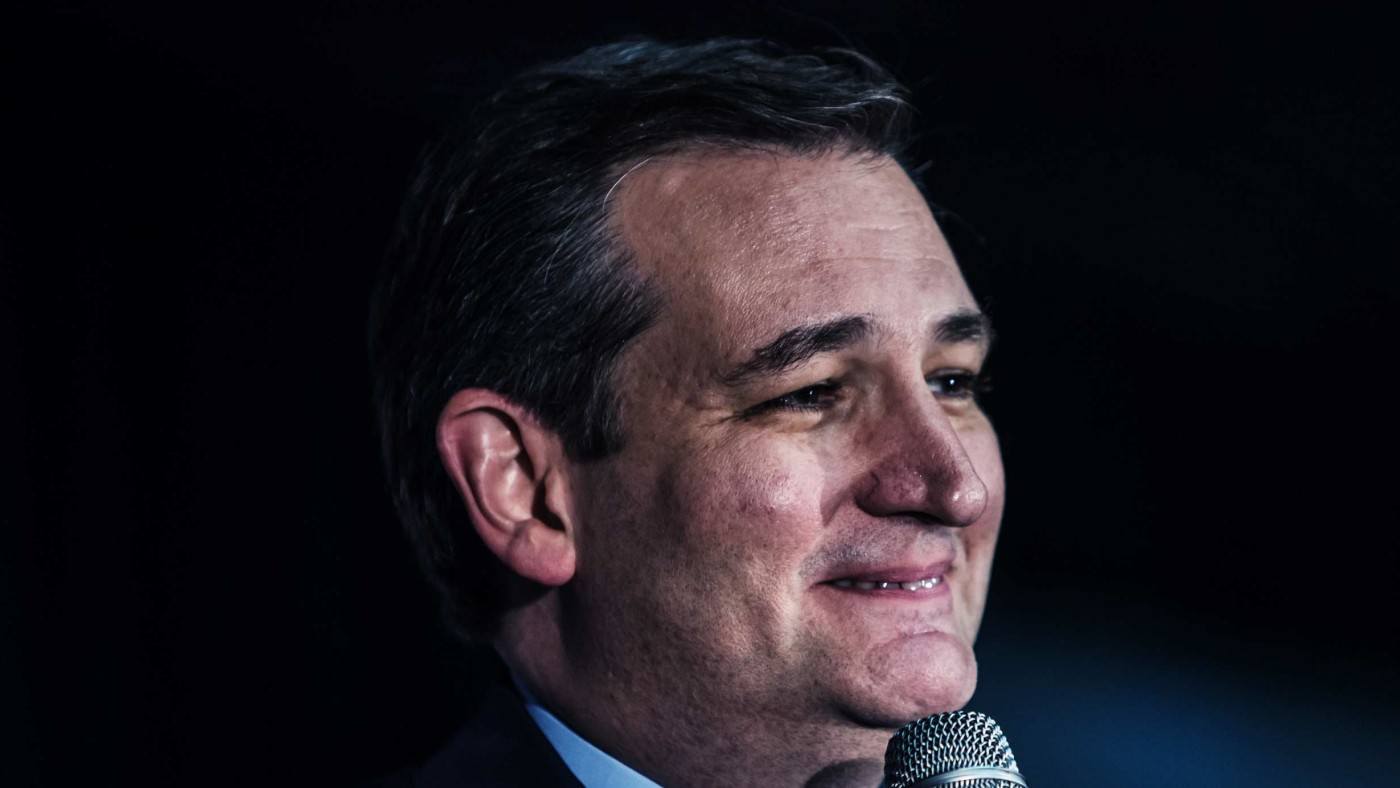

And yet, despite that, it still matters. If Donald Trump had managed to win in Iowa, even sceptics might have struggled to retain their certainty that Trump’s castle was built on foundations of sand. But if Republicans think their troubles are over they are guilty of swapping one delusion for another. When Ted Cruz is, at least for now, your unlikely saviour you know you are in deep, deep, trouble.

Not that Democrats have any great reason to be feeling smug today. Bernie Sanders, the closest thing to a socialist mainstream American politics can offer, wrestled Hillary Clinton to an effective draw in Iowa and may yet win in New Hampshire (a state bordering his own Vermont stronghold). Clinton’s inability to rout perhaps the only Democrat who could make half the Republican field look electable is hardly a sign that all is well on the Democratic side of America’s great political divide. But then who can really be impressed or enthused by a campaign run on an appealing combination of identity politics and personal entitlement?

In that respect, everyone is right to suppose that Marco Rubio is the biggest “real” winner in Iowa this year. His third place finish allows him to present himself as the most plausible “mainstream” alternative to the Scylla and Charybdis of Trump and Cruz. Time for the party to put aside its doubts about young Marco and rally behind the only sane guy in the asylum. That, at any rate, is the pro-Rubio argument now.

And yet many of the people who caucused for Trump and Cruz have no great interest in rallying to anyone who is part of the ordinary and familiar political “establishment”. The establishment, they think, is the damn problem in the first place.

National-populism – the chief feature of Trump’s campaign and, to a lesser degree, the driving force behind Cruz’s march on Washington too – is hardly a new phenomenon. Nor is it a given that the mainstream establishment always ends up deciding the identity of a party’s candidate. The ghosts of Barry Goldwater and George McGovern whisper from beyond the grave, reminding us that the impossible is always more possible than you might like to think.

Nor are the sentiments driving this revolt on the right altogether new. As early as 1966 the Harris polling organisation created an “alienation index” measuring responses to these five statements: “The rich get richer and the poor get poorer”; “What you think doesn’t count very much”; “The people running the country don’t really care what happens to you”; “People who have the power are out to take advantage of you”; “Left out of the things around you”. Back then, plenty of people answered ‘Hell, yeah’ to each of these propositions; plenty more would do so today.

In one sense this makes very little sense. Whatever might be said of Barack Obama’s presidency, the United States is not coming apart at the seams in the manner it seemed to be in the 1960s (a decade which might only be eclipsed by the 1860s and the 1930s in any race to determine the worst decade in American history). Nonetheless, there is a widespread apprehension that something, somewhere, has gone rather badly wrong. The system no longer works as it should. This is not a wholly mistaken feeling, either.

After all, the little guy, the ordinary joe, the stout-hearted backbone of Main Street America, gets the shaft and Wall Street is rewarded for screwing the great American middle-class. Meanwhile, overseas, far from being a new American century is seems more probable that these will be years of relative decline. The ‘greatest generation’ is dying and will be replaced by, well, what exactly? The baby boomers? Give me a break.

So perhaps it is not so surprising that American politics is so very febrile these days. Add Ben Carson to the mix, and the ‘revolting’ Republican candidates were supported by more than 60 percent of caucuses in Iowa. That does not bode well for the future of either this primary season or the Republican party. Even if a ‘mainstream’ candidate thwarts Trump and Cruz, they will win the nomination on the basis of being the least-objectionable, modestly-electable candidate in recent years. Enthusiasm will be limited.

Trump’s candidacy has been dismissed as a piece of performance art and there’s enough truth in that for the sentiment to be worth something. But Cruz, the actual winner in Iowa, bases his campaign upon the proposition that the American government can be saved by destroying it. That might appeal to the millenarian torch-and-pitchfork crowd but it does not seem likely to answer the problems so manifest in American politics today. But if the alternative is Hillary Clinton you can understand the despair.

What a country; what a time to be alive.