“It was the rise of Athens, and the fear that this inspired in Sparta, that made war inevitable.”

War is usually what happens when a rising power challenges an established one. It’s called the Thucydides Trap, and it is the politics of the playground. It is the geopolitical equivalent of the New Cool Kid turning up and threatening, just by his presence and his capabilities, to take power and influence away from the Established Cool Kid(s) and his tribe. The NCK will be welcomed by the ECKs into the existing order (read US-led World Order), if and only if he doesn’t challenge its power structure or, worse, its raison d’être. If he does that, he is likely to be ostracised (read Cuba, North Korea, Russia or Iran). The trouble only starts when the NCK builds his own little colony of followers, particularly if they include defectors from the ECKs, and establishes a threat to the existing set up. More on this later.

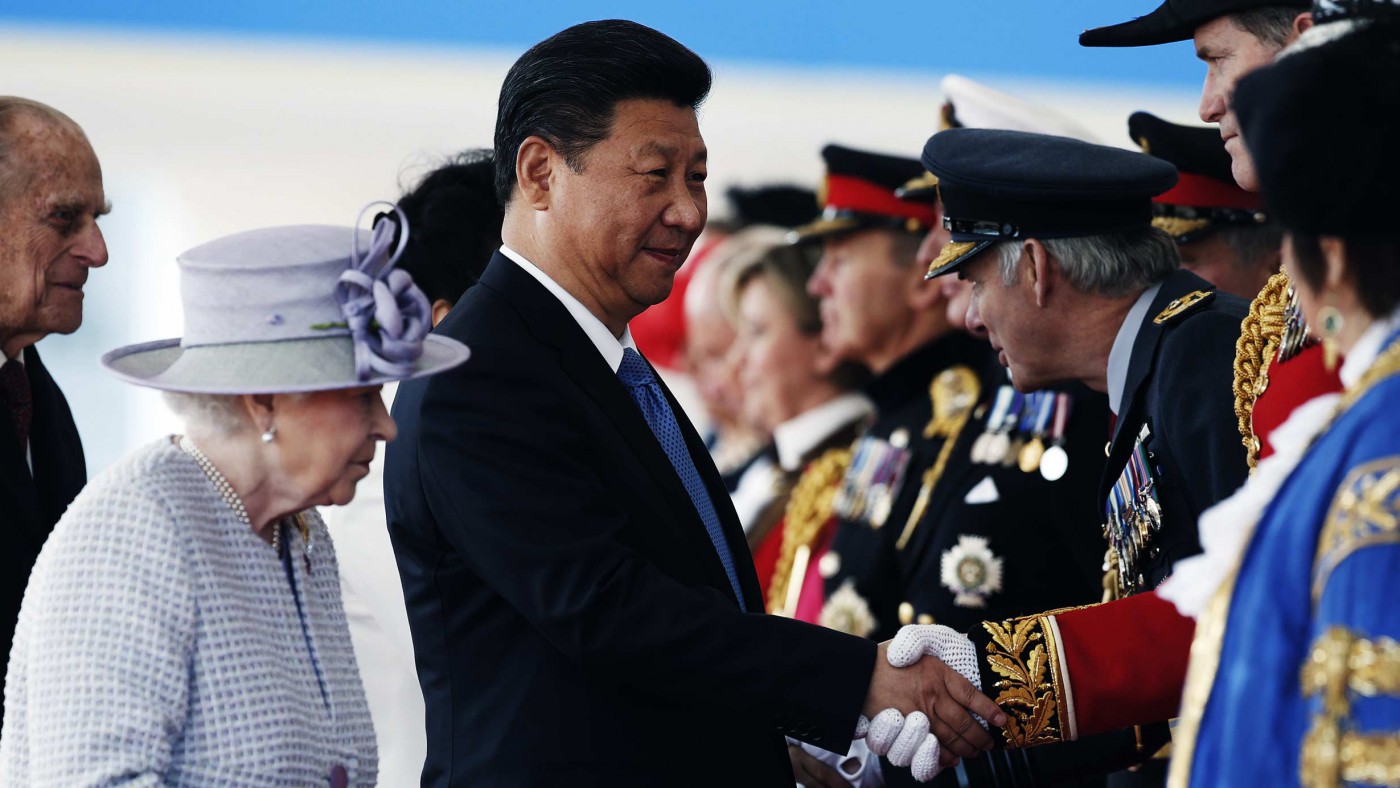

In European affairs, it has actually been even sillier than this. An absurd aristocratic family feud over power, status and rights to Africa led ultimately to the First World War. Given what followed, not only is it hard to imagine that Kaiser Wilhelm II and King Edward VII were closely related (with the former attending the latter’s funeral) but that the Kaiser wrote to Theodore Roosevelt, concerned with the rapid emergence of the German Navy, claiming: “I feel myself partly an Englishman. Next to Germany, I care more for England than any other country. I ADORE ENGLAND!” Bear that in mind when you see pictures of President Xi on his trip to the UK, with his plate of fish and chips, because much of geopolitics is powered not by mutual affection but by loss aversion on a massive and sometimes devastating scale.

In many respects, China is already the US’s equal. Measured by purchasing power parity, China is the world’s largest economy. It is also the world’s largest importer of oil, and the country which holds the most U.S. debt. Under President Xi, it has begun making bold claims to large parts of the South China Sea, covering sea lanes that account for 30% of global trade. This makes China’s courting of Britain a major concern for the US.

In his speech in London today, Xi said that China and Britain are becoming increasingly interdependent. Let’s be honest; he’s just being polite. China doesn’t need Britain anywhere near as much as Britain seems to need China. Despite facing major domestic headwinds, China added an economy the size of the Netherlands or Turkey in 2014 alone. As Fraser Nelson noted earlier this week, President Xi’s visit looks more like a landlord inspection rather than a meeting of equal powers.

Britain rolls out red carpet for state visit of Chinese president Xi Jinping: http://t.co/PeeXSJuLbH by @PARoyal pic.twitter.com/QnrjzgR0rW

— Press Association (@PA) October 19, 2015

On Friday, Xi will be flown up to Manchester and asked to pay for the Chancellor’s Northern Powerhouse initiative, designed to hook up the north of England’s great cities into one economic unit. The new nuclear power station at Hinkley Point will be one-third owned by China, and Chancellor George Osborne has encouraged the Chinese to bid for contracts to build HS2.

In some respects, this is fine. Britain provides an outlet for excess Chinese savings as it continues to rebalance its economy from one over-reliant on domestic infrastructure and heavy industry to one based on services and domestic consumption. The UK is a trading island which is not self-sufficient in food and basic natural resources. It needs to pay its way in the world and do more to cut down on its unsustainable current account deficits. If Chinese investment helps make the British economy more productive in the long-term and London becomes the first clearing house for the yuan outside Asia, then more or less everyone benefits.

But in other respects, it really isn’t fine. “The UK is not a big power in the eyes of the Chinese. It is just an old European country apt for travel and study.” That was the editorial view of The Global Times, an official Chinese newspaper owned by the Chinese Communist Party.

My concern is not just about the human rights abuses in Xinjiang or Tibet, the authoritarian attitudes to government, the cyber-crime or the British steel factories hung out to dry. It’s about geopolitics.

The Treaty of Nanking, which in 1842 allowed Britain to flood Chinese markets with opium, was humiliating for China, and accelerated its development in the same way that the arrival of Commodore Perry led to the Meiji Restoration in Japan. In 1994, well after setting in train his market polices, Deng Xiaoping spoke of the ongoing strategic imperatives for his reforms. “We must bide our time and hide our capabilities”.

China is now showing its strength to the world, whether by establishing a multinational development bank (of which Britain is a member) that seeks to rival the World Bank, building a very long road across Eurasia from Beijing to Pireaus, or buying up important strategic assets of an old European country.

To be clear, I don’t think China is interested in running the world along colonial lines. It’s not going to appear one day in Liverpool, once home to the global cotton trade, aboard gun-ships just to show who is now wearing the trousers. There is a wonderful pacifism about Confucian culture that we can learn from.

But I don’t think China is interested in global dominance, in the same way that I don’t think Kaiser Wilhelm wanted to take over the British Empire with his Imperial Navy. He was more concerned with defence tinged with a nationalist desire for autonomy and self-determination. Before the Schlieffen Plan and Weltreichlehre came into being, there was an attempt to forge an alliance with Britain to neutralise France. Germany was rebuffed and the Kaiser concluded, disastrously, that his country needed a proper navy to be taken seriously.

Likewise, China is probably not interested in displacing the U.S, but that doesn’t matter. In seeking a multipolar world in which it can bring its hefty weight to bear on the world stage, it will fundamentally change how international affairs are conducted. The yuan will challenge the reserve status of the dollar. Global trading routes will be contested. Westphalian politics will become more essential in holding the global balance of power – and that requires strong leadership. India, Pakistan and Iran will become renewed centres of strategic interest along China’s new Silk Road. And there is a heightened risk that the Middle East could turn into a theatre for more global proxy wars.

Returning to the analogy of playground games: from an American point of view, Britain – still coming to terms with no longer being a leading world power – is flirting dangerously with the new kid. China has turned up in a shiny new Porsche and Britain has jumped straight in. By signing up to the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and courting large amounts of investment, Britain is trading economic security for political risk. It would be harder for the UK to align with US interests on China in the future if it chose to do so.

Evan Medeiros, who was a former top Asia adviser to President Obama, said this to the Financial Times about the growing partnership, in the context of US concerns over the British government’s accommodation with human rights abuses in China:

“If there is one truism in managing relations with a rising China, it is that if you give in to Chinese pressure, it will inevitably lead to more Chinese pressure,” he says.

The trouble is, by involving rising China ever more closely in the British economy and its foreign policy, the government may have fallen into a trap, perhaps not yet of Thucydidean proportions, but one which drags the world closer to one and from which it will be tougher to escape.

The West narrowly avoided a war with the Soviet Union, because there was strong and united Western leadership, clear allegiances and the threat of nuclear annihilation. But by cozying up with China – the rising superpower – Britain may be complicating the transition to a multipolar world, with potentially dangerous consequences.