It was a pleasant surprise to be quoted by the Chancellor when he presented his Budget last week. In 2017, I wrote a short paper for the IEA titled A Rational Approach to Alcohol Taxation in which I said that the way we tax booze in Britain ‘defies common sense’. Rishi Sunak quoted these words, along with the view of the Institute of Fiscal Studies that the alcohol tax system is ‘a mess’.

And so it is. My argument in 2017 was that if we must tax alcohol, we should tax units of alcohol rather than taxing arbitrary volumes of fluid. I wrote:

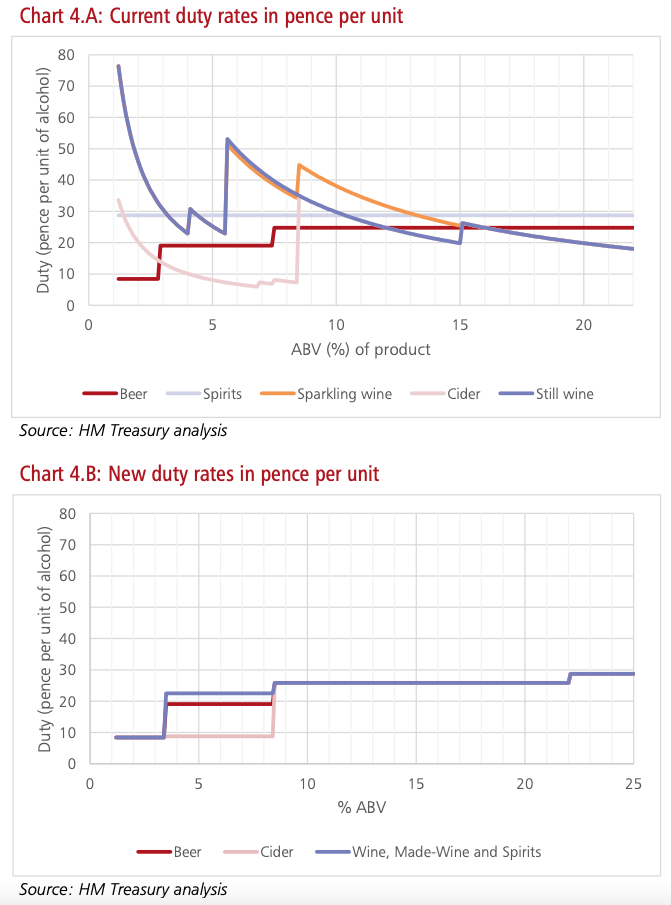

‘A unit of alcohol is taxed at 27.7p if it happens to be in a glass of whisky but at just 7.8p if it is in a pint of cider. If the cider is strong, the tax is less than 7.8p, but if it is strong and fizzy the tax is 33.6p. Similarly, the tax on a unit of alcohol in a glass of wine amounts to 19.8p unless the wine is sparkling, in which case it is 25.4p.’

These peculiarities have arisen over several centuries thanks to special pleading from various interest groups and, in more recent decades, EU legislation. The alternative I suggested was a straightforward Pigouvian tax. You work out the cost of alcohol’s negative externalities (i.e. the cost imposed on people other than the drinker) and tax each unit of alcohol at a rate that adds up to that cost. At current rates of consumption, I estimated this to be 9p per unit, significantly less than the average rate of tax on alcohol but more than the lowest rate.

The Government intends to move things in this direction. The tax system will be simplified. Alcohol will effectively be taxed by the unit, although the rate will vary between beer, wine, cider and spirits. The tax rate will be the same across each category except for very strong or very weak versions of the drink. The rate will also be slightly lower in pubs.

But what you really want to know is whether it is going to make drinking any cheaper. That depends on what you drink. If you are a Prosecco Mum, it’s good news. The discrimination against sparkling wine will end. If you drink small beer, it’s good news. A lower tax rate will apply to beer with an ABV of up to 3.4%, not up to 2.8% as is currently the case.

If you drink wine with an ABV between 6% and 9%, you will make a substantial saving, but if you drink wine with an ABV above 12.5% you will be taxed more. And if you drink spirits, you won’t notice a difference because spirits have always been taxed in a logical, though exorbitant, way. Overall, the Treasury does not expect to make any more, or any less, revenue from alcohol duty than it does today (the tax rates will rise in line with inflation).

This is a step in the right direction and the Treasury should be congratulated for being prepared to overhaul this dog’s dinner of a system from scratch. However, in two crucial respects, it will remain a long way short of rational.

Firstly, there will still be enormous differences in the tax rates for alcohol depending on what kind of drink the ethanol is in. A unit of alcohol in a standard pint of beer will be taxed at 19.1p. In a pint of cider, it will be just 8.8p. A unit will be taxed at 25.9p if it’s in an average bottle of wine and at 28.7p if it is in a bottle of whisky. This partly reflects the different costs of production (cider is relatively expensive to produce, for example) and it partly reflects public health concerns (spirits can be drunk quickly). But it also reflects political considerations. There are a lot of marginal constituencies in the cider-making south west.

Secondly, the tax rates are too high to be described as Pigouvian and the total tax take will far exceed any reasonable estimate of the external costs of alcohol consumption. Perhaps it was asking too much of the Chancellor to stop using drinkers as a cash cow when the national debt is £2.2 trillion, but we should remember that British alcohol taxes are amongst the highest in Europe. Most EU countries do not have wine duty at all!

One of the reasons the government has introduced the new system – aside from the influence of compelling research from top think tanks – is that it is keen for drinks producers to reduce the alcohol content of their products. Tax incentives in the duty system currently exist for this, but they have the unintended consequence of encouraging the industry to produce drinks with an alcohol content just above or just below an arbitrary threshold. The new system largely avoids this. A 13% wine will be cheaper than a 14% wine which will be cheaper than a 15% wine, whereas there is currently a simple threshold at 15%.

The drinks industry and public health groups are largely united in supporting the production of lower strength products. I am indifferent, but at least the new system will provide the incentives more effectively. As I pointed out in my original paper, a lower tax rate for beer below 2.8% ABV is a waste of time because there is almost no demand for it. The new threshold of 3.4% is still lower than I would like (I proposed 3.6%), but it gives brewers a more realistic target.

Don’t be surprised if you start seeing lots of bitter popping up at 3.4% ABV over the next few years. You’ll have to drink a lot of it, but it will be cheap.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.