Amid the shock (and horror) of election night, the snap verdict was clear: this was the UK’s Brexit election. As traditional Tory seats like Canterbury and Kensington turned from blue to red, it seemed obvious that British politics had divided along a new fault line: Leave vs Remain.

Since then, many Brexiteers have fought a rhetorical rearguard action. They have argued that the vote wasn’t about Brexit at all, given that the Labour Party stood on a manifesto that effectively endorsed hard Brexit, and the hard-line Remainers – the Lib Dems and SNP – had an even worse night than the Tories.

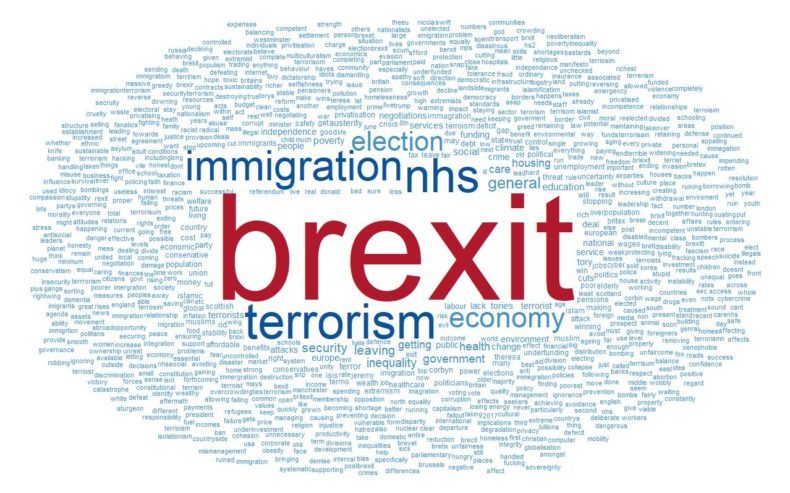

Now, we have the results of the British Election Study’s survey of 30,000 voters. And the headline finding is that it was the Brexit election after all. However little attention Jeremy Corbyn and Theresa May gave to the issue during the campaign, it was at the front of voters’ minds. Asked what they thought the single most important issue facing the country was, more than one in three said our departure from the EU.

A word cloud of answers to the question “what is the single most important issue facing the currency?” Source: British Election Study

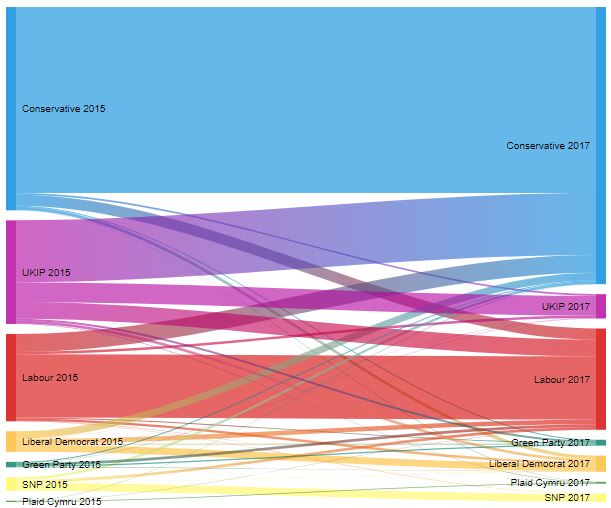

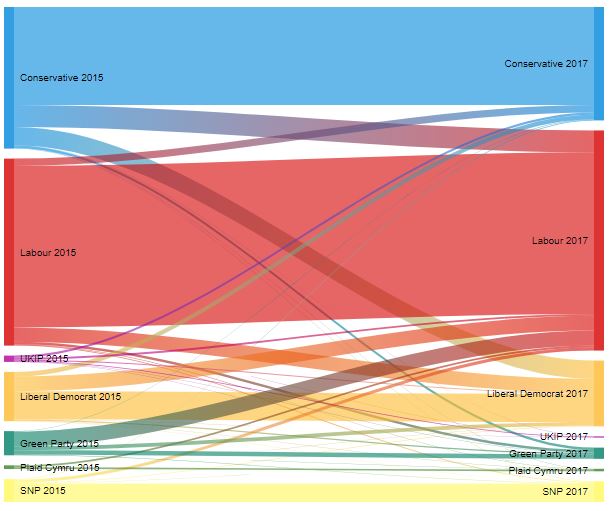

Not only was Brexit what voters said mattered – it was what they voted on. People’s preference for Leave or Remain appeared to loosen party political allegiances, with Labour – in spite of its leader’s longstanding Euroscepticism – hoovering up Remainers and Leave voters rallying behind the Conservatives.

Top: Where the Leave vote went. Bottom: Where the Remain vote went. Source: British Election Study

But look a little closer at the data, and another pattern emerges. British politics isn’t about Leave vs Remain. Rather, Leave vs Remain is itself a symptom of much bigger, deeper changes.

That, at least, is the conclusion of a fascinating new study by academics Will Jennings and Gerry Stoker. Jennings and Stoker mapped the change in Conservative and Labour vote share against the size of the Leave vote in every English constituency. And inevitably, they identified a clear correlation between the size of a constituency’s Leave vote and the change in Conservative vote share between 2015 to 2017.

But here comes the surprising bit. The correspondence between Leave vote and change in Conservative support is more pronounced in the long run, between 2005 and 2017, than over the last two years.

In other words, the association between voters’ views on Brexit and their party-political preferences is, as Jennings and Stoker put it, a “symptom of the long-term social and political changes that preceded [the referendum] – rather than being the focus of an immediate Brexit realignment of English, and British, politics itself.”

Voters weren’t using the 2017 election to refight the referendum. Instead, both votes were battles in a longer electoral war – between two increasingly distinct cultural and economic groups.

Brexit Britain, then, didn’t become bitterly divided on June 23, 2016. The divides have been there for some time. They were just easier to ignore before the referendum.

For Jennings and Stoker, this divide is between cosmopolitan and non-cosmopolitan Britain. Though it can also be understood in David Goodhart’s much-discussed – and often over-simplified – distinction between the Anywheres and the Somewheres. Or, to put it in economic terms, the divide between citizens living in places connected to global growth and those who are not.

Jennings and Stoker’s data show that cosmopolitan Britain has become inexorably more Labour-supporting, while non-cosmopolitan parts of the country have tilted further towards the Conservatives.

Whether Brexit is a cause or product of Britain’s new political rift may seem an academic point given that we have already voted to Leave. But if you want to understand what is happening in British politics, and why, appreciating how these dividing lines work is essential.

For example, if there was no Brexit realignment, then none of those politicians – on either side – who are claiming the election result was a specific mandate for their particular position on Brexit have a leg to stand on.

Similarly, it turns out that Brexit is not the be-all and end-all of British politics. The Conservative Party’s lack of appeal in places like Kensington may have been about more than their support for a clean break from the EU.

That means, for the Tories, softening their stance on Brexit would be no panacea – because their problems in such places are more profound. Likewise, winning round Brexit-voting Labour heartlands involves more than becoming the party of Brexit.

To her credit, Theresa May seems to understand much of this. She has rarely missed an opportunity to explain that the vote to leave the EU was about a broader dissatisfaction with the status quo. Her mistake was to oversimplify Britain’s new dividing lines, painting cosmopolitan Britain as a well-heeled liberal elite whose interests have been prioritised over those of the left-behind. But as the success of Jeremy Corbyn’s anti-austerity message showed, there are low-paid workers in big cities who feel just as economically precarious as those in “left behind” parts of the country. And many cosmopolitans still took enormous offence at being labelled “citizens of nowhere”.

The broader message of these findings is also clear. To win and wield power, you need to bridge the new divide. That need not mean a descent into centrist platitudes and meaningless triangulation. But it does mean finding a vision that appeals to cosmopolitan as well as non-cosmopolitan Britain.