China loves anniversaries. In October, the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic will be celebrated with public displays of military strength, and admiration for the Party’s accomplishments. Some anniversaries, though, are shunned. While citizens of Hong Kong will doubtless note June 4 to remember the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests and attend a recently opened 4th June Museum, mainland China will shun any and all references to it.

Preparation is already under way to detain people, suppress protest and commentary, and block references including in global sources, such as Wikipedia. For the Communist Party, it remains a sensitive and potential tool that could energise those who would criticise the Party or invoke the ‘western values’ that are forbidden in Xi’s China.

No one knows to this day how many people were killed on the night of the 3rd June 1989. The government figure is 241, including soldiers, and 7,000 wounded. Since then, unofficial estimates put the death tool at about 3,000, but in a relatively recently declassified secret diplomatic cable from the then UK Ambassador to Beijing, Sir Alan Donald, he revealed that the morning after the tanks had rolled in to the square and opened fire, it could have been as high as 10,000.

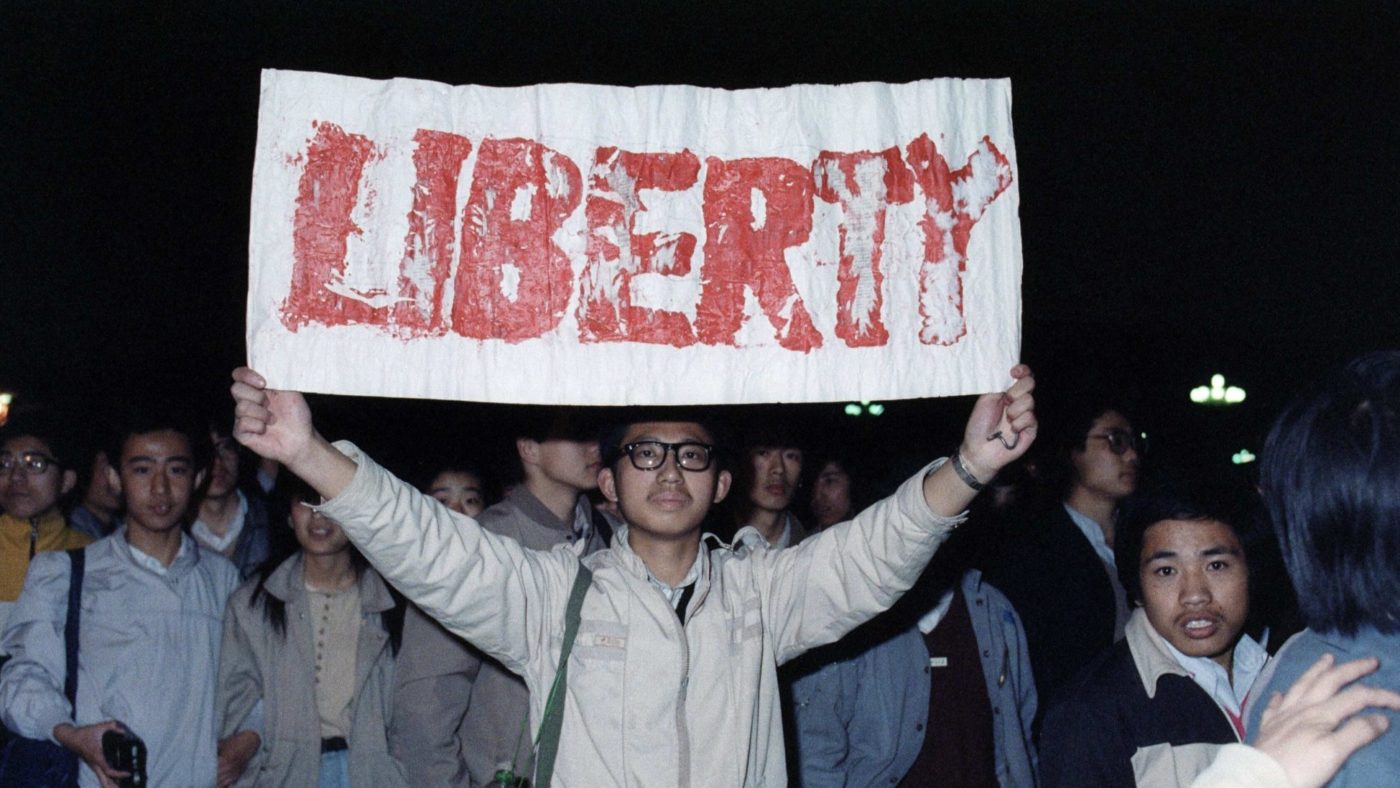

In the run-up to the event, students were agitating against rising inflation, inequality, and corruption, and wanted to see new reforms. The death of Hu Yaobang, general secretary of the Party, who had been forced to resign in 1987 over pro-democracy reforms, served as a catalyst for the protestors, who then elevated him to a sort of martyr for the cause of liberalism. In the last weeks weeks of May, martial law was imposed, but hard-liners in the government eventually won the argument to take more drastic action.

Visitors to Tiananmen Square have nothing to see or remind them what happened in June 1989. To recall Tiananmen is to succumb to ‘historical nihilism’, or scepticism about the Party’s version of past events in which the defamation of Communist Party heroes and great leaders is a civil offence.

Historical nihilism is one of the seven ‘don’ts’ in the now infamous Document No: 9 that universities and media organisations were urged in 2013 to not speak about or ban. These include other topics such as universal values, freedom of speech and media independence, constitutional democracy, civil society, civil rights, neoliberalism, and judicial independence. In the Party’s narrative, past success and, perhaps more importantly, future greatness are directly attributable to the correctness of the Party, the role of the state in the economy and society, and the architecture of industrial and technology policies.

On the 30th anniversary of Tiananmen, there is, of course, no mass democracy movement, much stifling of dissent in Xi’s China, and methods of social control have become more sophisticated and complex with the development of artificial intelligence and big data exploitation. Yet, it is also interesting to note over the last year or so, as the trade war between the US and China’s evolved, a surprising upsurge in disquiet and pushback against the government.

Academics and some former officials have questioned the official narrative and sought to shift the focus for China’s success elsewhere, for example to ‘marketisation’, entrepreneurship and learning from the rest of the world.

Some commentary, focusing on intellectual property as a product of the institutional structure that nurtures it, has emphasised the significance of the rule of law and other components of Document No: 9 without which, China’s potential might be restricted. Still other essays have appeared briefly to criticise the authorities for policies that are allegedly leading to a loss of private sector confidence and dynamism.

A handful of former officials have alleged that China’s approach to the US is leading the country down a dangerous path, and one former Finance Minister has said that Xi Jinping’s core technology strategy “Made in China 2025’ is a waste of taxpayers’ money.

It goes without saying that no one dares criticise the President himself. And no one is suggesting that these and other critical voices, invariably silenced or their work removed from public inspection, represent anything organised.

Yet a country that resolutely forbids its citizens to remember the role and reasons that thousands of their fellows played in a political movement for reform, and those that paid with their lives, isn’t quite the all powerful and confident country that it purports to be.

A government whose leader was recently quoted in the country’s main newspaper, People’s Daily, as warning that the role of state enterprises and the Party as the backbone of the economy must not be jeopardised, doesn’t not come across as the confident enabler of needed reforms. That undermines the Party’s raison d’etre, which is to rule unchallenged.

The 30th anniversary of Tiananmen will come and go ghost-like in China, but the event will remain part of China’s narrative, despite the Party’s best efforts. We should remember that the more that authoritarian governments try to control their narrative, the harder it is to stop people developing their own.

Tiananmen Square participants were inspired by predecessors, who in 1919 formed the May 4th Movement, from which the Communist Party emerged, and the centenary of which was recently acknowledged in China.

Since last year, students who support the Party’s Marxist origins and ideology have been among the latest victims of top-down repression. Some of their leaders have been taken into custody, some have disappeared. Moreover, some groups of students and workers have been trying to organise factory workers in southern China. Around 50 labour activists are in detention.

These students and workers claim loyalty to and respect for their country, but also the right to oppose and protest their government. As aspirations and expectations develop, it won’t be easy to contain the latter. Shunning celebrations is the easy part.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.