Last month on Earth Day representatives of 170 countries rolled into New York to sign the landmark Paris Agreement on Climate Change. All in all 60 heads of State were there, from François Hollande (the first to sign) to Robert Mugabe. Undersecretary for Climate Change Lord Bourne signed for the UK, US Secretary of State John Kerry signed while holding his granddaughter in his arms. A beaming Maroš Šefčovič, Vice President of the European Commission responsible for the Energy Union was on hand to endorse the deal that his junior, EU Energy Commissioner Miguel Arias Cañete had fought so hard to deliver.

As of today, some 175 states have signed the accord, including all 28 member stets of the EU and the EU itself (which is a separate signatory – more on that later. There is of course a gulf between signing and delivering, but UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon believes that the symbolic act will act as a catalyst for negotiators already assembling in Bonn tasked with divining a strategy to implement the Paris Accord.

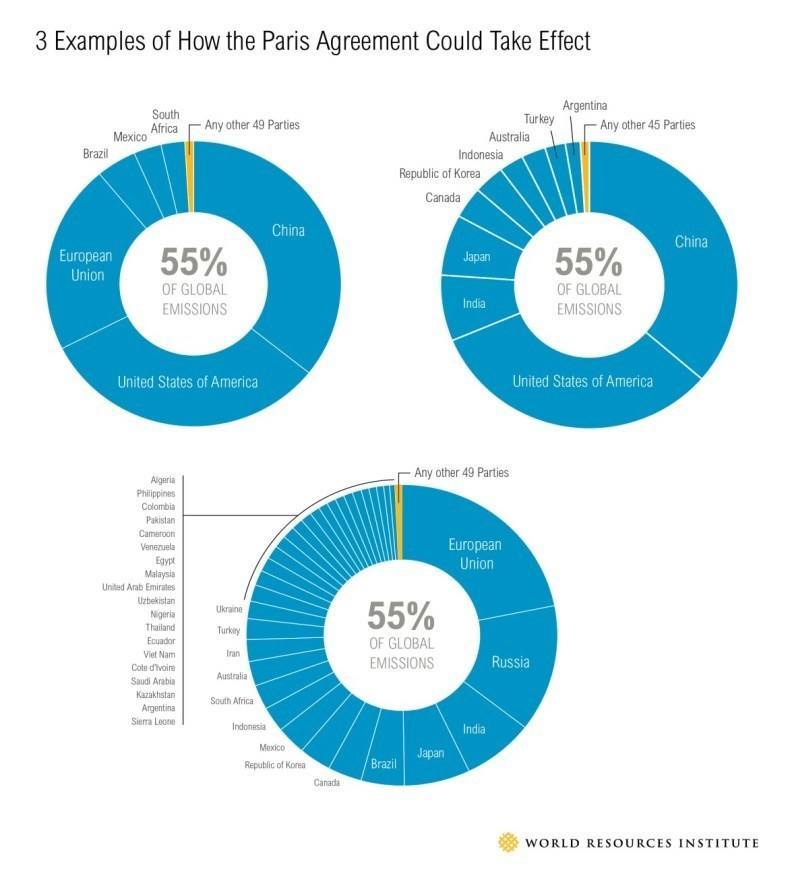

However despite the plethora of politicians gathered in New York queuing to sign up, the Paris Accord will come into force only when at least 55 states responsible for at least 55% of the global emissions ratify the deal via their national parliaments and then deposit the ratification instrument with the UN. So far 15 countries – Barbados, Belize, Fiji, Grenada, the Maldives, the Marshall Islands, Mauritius, Nauru, Palau, St Kitts and Nevis, St Lucia, Samoa, Tuvalu, Somalia and Palestine responsible for only 0.04% of global emissions, have ratified. A further 27 countries have pledged to ratify this year (as their domestic legislative arrangements allow), including the US and China and the UK. This will bring the country total to 42 and the emissions total to 49.3%, some 6% shy of the promised land.

There are three ratification scenarios that could play out, summarised in the charts. As the third greatest emitter of CO2 the commitment of the EU is important, but as the charts show, it isn’t necessarily essential, which given the situation in the EU, is perhaps just as well.

In order for the EU as an entity to ratify the Paris Accord, each of its 28 members must secure passage of the agreement through their respective national (and in some cases, regional) parliaments. As is always the case with the EU, the caravan will travel at the pace of the slowest camel.

To illustrate the point, Belgium has seven parliaments: The European Parliament, The Federal Parliament, The Federated French Speaking Community Parliament, The Parliament of the Brussels Capital Region and The Flemish Parliament – all of which are in Brussels, then you have the Parliament of Wallonia in Namuur and The German Speaking Communities Parliament in Eupen. With the exception of the European Parliament, all of these parliaments must agree to the Paris Accord before Belgium is in a position to ratify. Scheduling issues alone could add weeks to Belgium’s ratification process. And that assumes that the MPs from across the EU actually want to support the Paris Agreement. In light of recent elections across the EU, can such support be assumed? Indeed, fears are now growing inside the Brussels’ bubble that the Paris Accord will be enacted before the EU puts collective pen to paper.

The EU’s role in addressing climate change has always been ill defined. It has relied upon a collective belief that it is the job of the EU to tackle climate change, rather than a clearly agreed remit or definition of role. There is little doubt that the European Commission is an active participant in climate negotiations, a role exemplified in Paris by EU Energy Commissioner Cañete’s critical part in establishing the ‘High Ambition Coalition’ of nations which backed inclusion of a reference to a 1.5oC temperature aim in the final agreement. However, the 28 EU Member States are equal participants in the negotiating process, and whilst it is important to recognise the key role of Señor Cañete, recognition should also be given to Laurent Fabius, the chair of the gathering, Amber Rudd from the UK and Barbara Hendricks from Germany. The 28 member states may agree on the need to address climate change, but exactly how is anything but agreed, particularly when it comes down to financing (as these agreements so often do).

The Paris treaty will be ratified, of that there is no doubt. However, if it is ratified without the signature of the EU, then questions of credibility and leadership will necessarily be laid at the door of EU and its energy representatives. To be beaten to the mark by climate sceptical nations like Australia, China and India should serve as a wake-up call the EU; the torch of leadership is slipping gently from its grasp. It will not pass unnoticed in an ever more Euro-sceptical EU. If the EU is going to continue to claim a leadership role in future negotiations on climate change (or any of the other pan-global threat facing Europe) then it has to be more than rhetoric and handshakes, it has to start delivering. Otherwise its name will appear at the bottom of future treaties rather than near the top.