This piece was originally published on the Centre for Policy Studies’ new monthly newsletter, which you can sign up to here.

UK GDP figures have been in the headlines again recently, with initial estimates pointing to unexpectedly firm economic growth of 0.6% in Q1 2024 – twice the rate recorded in the Eurozone.

While undoubtedly good news for the Government, this data may have been a disappointment to some of its critics, not least Rachel Reeves, as well as various prominent Remainers – the people who have been pushing a narrative of economic decline ever since the 2016 Brexit referendum.

But at least in part, relatively firm economic growth came as a surprise because professional economists have developed a habit of underestimating British growth prospects. This seems to be particularly true of economists working in international institutions such as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Of course, if you criticise economic forecasting agencies these days, you run the risk of being maligned either as a populist enemy of technocratic competence as Michael Gove was (unfairly) in 2016; or else as a Trussite conspiracy theorist obsessed with the machinations of a nebulous ‘anti-growth coalition’.

Nevertheless, given how central GDP forecasts are to policymaking and our national conversation (rightly or wrongly), economic forecasters cannot be beyond criticism if there is clear evidence that they are underperforming. And in the case of the OECD, there does seem to be such evidence.

Every November, the OECD publishes an ‘Economic Outlook’ containing growth forecasts for the current year and two years ahead. We can get an idea of how good the OECD is at modelling the UK economy by comparing its past forecasts to the outturn – both for the UK and, crucially, for our G7 peers.

In compiling the dataset for this exercise, we have used forecasts going back to the November 2012 ‘Economic Outlook’. We have excluded forecasts covering the Covid years of 2020 and 2021 for obvious reasons. That leaves 27 data points for each of the G7 countries – 189 data points in total.

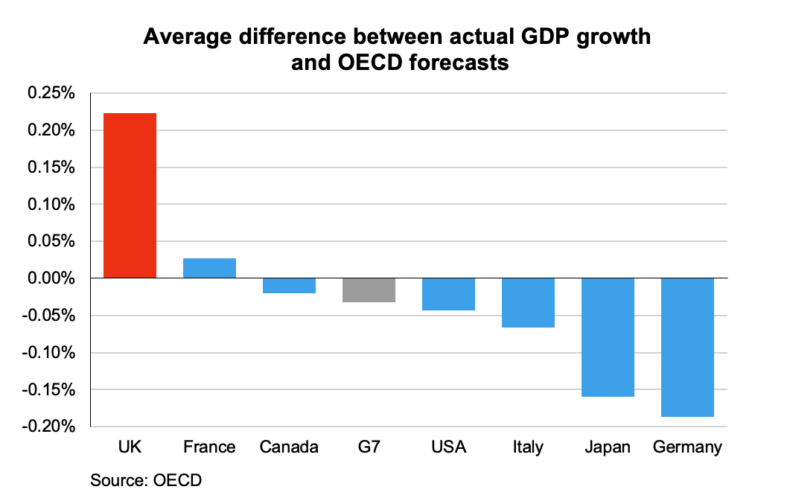

We can then compare each of these 189 forecasts to the actual growth rates recorded in the years 2012-19 and 2022-23. This allows us to build up a picture of how much, on average, the OECD has underestimated or overestimated growth for each country. The results of this are displayed on the graph below.

Strikingly, the OECD underestimated annual UK GDP growth by 0.22% on average across the period. In contrast, it overestimated Japanese and German growth by 0.19% and 0.16%. In fact, the only other G7 country where the OECD tended to undershoot in its forecasts was France, but only by 0.03%. Across the group, the OECD overestimated growth rates by 0.03%.

In other words, OECD modelling seems to systematically underestimate UK growth prospects in a way it doesn’t for any of our peer countries. The obvious question is: why?

It’s tempting to assume a pessimism about Brexit has been at play, but the forecasts were actually more out of kilter in 2012-15. Over those years, a pessimism about the Coalition government’s attempt at ‘austerity’ might have been a factor.

But it could also be that there’s something deeper at play. Services account for a much larger share of our GDP than is this case in other G7 countries, so perhaps the OECD model struggles to capture that, while overestimating growth in economies like German and Japan where manufacturing accounts for a much larger share of economic activity.

It could even be because the OECD was using flawed demographic and migration forecasts for the UK – an issue discussed at length with reference to the Office for National Statistics and Office for Budget Responsibility in a recent Centre for Policy Studies report, ‘Taking Back Control’.

In truth, we don’t know the answer yet – but next time you hear an international organisation expressing alarm about Britain’s growth prospects, it may be best to take their prophecies with more than a pinch of salt.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.