Britain’s competition regulator, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has published a report on the state of competition in the UK. (Disclosure: I was part of a group that gave some comments to the CMA during the drafting of this report.) The report relies heavily on aggregate data to make judgements about the health of competition. Unfortunately, this type of information is simply too crude to base sound policy recommendations on.

Concentration

Concentration measures, the focus of much of the report, show how much output in a sector is produced by each player. But these measures have uncertain policy implications. When concentration rises, it may be a sign that competition is weakening, as fewer and bigger firms are taking a larger share of the overall market, perhaps lowering the intensity of competition between those firms. But the opposite could be true too — like shoppers switching from an inefficient local shop for their groceries to a cheaper supermarket chain. That would raise concentration, but competition would be working as intended.

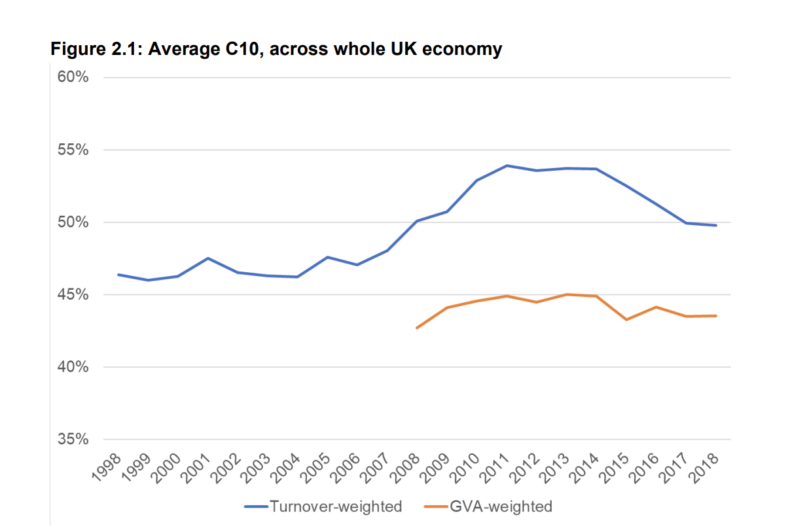

The CMA focuses on the output share of the top ten firms in each sector. It finds that, measured by turnover, concentration rose during the Great Recession and its aftermath, and then began to fall from 2014. By another measure, weighted by gross value added, concentration was effectively unchanged over the past decade.

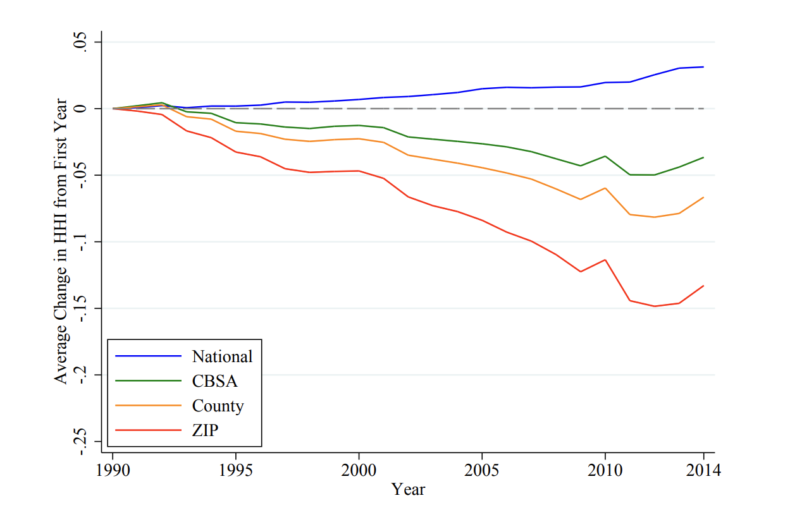

But, as well as concentration rising when shoppers choose larger and more efficient retailers, national trends can obscure local trends, which for most markets is what really matters.

In the United States, national-level concentration has been rising as local-level concentration has fallen. What this suggests is that more national-level firms are extending into more areas and competing with smaller firms that were once once dominant in their local areas. Think of Walmart or Tesco opening a new branch in a town that used to rely on an independent local grocer — national concentration will rise (because the national-level firm’s market share will rise) as local concentration falls. And in these cases competition is likely increasing as well.

Profits and mark-ups

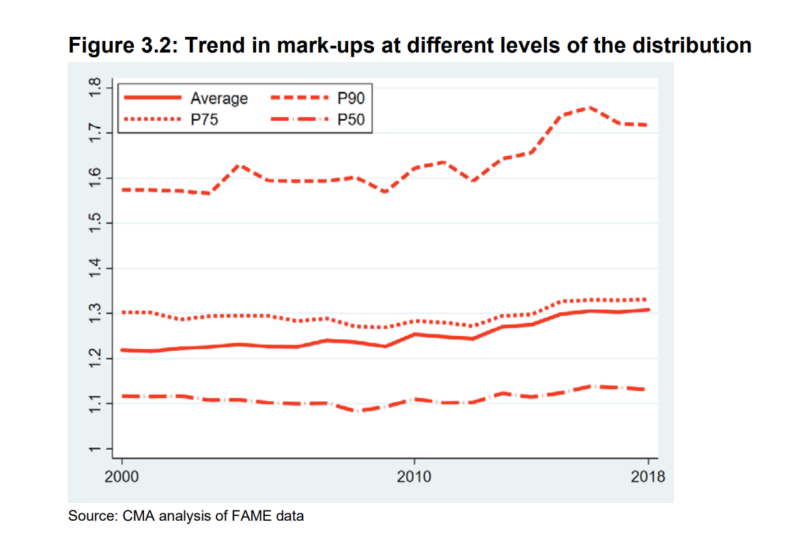

Markups measure the amount of profit that firms make on each product they sell. Across the economy as a whole, the CMA finds that they have risen slightly over the past decade, particularly among more profitable firms. This may be indicative of a problem — persistently high profits might suggest weak competition, since we would expect high profits in a sector to attract new competitors to capture those profits and, over time, compete them down as the businesses cut their prices to compete with each other. If that’s not happening, the incumbents may be avoiding competitive pressures in some way.

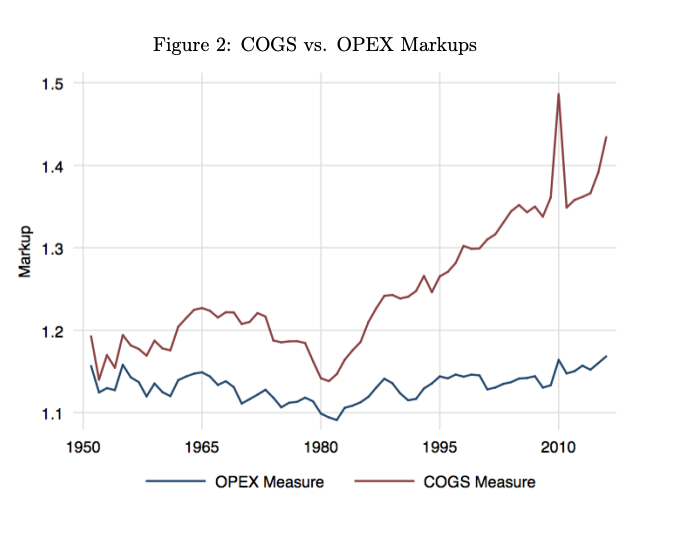

But there are alternative explanations, which the CMA points out may apply here. The first is that markups are larger in industries with higher fixed costs — if you’ve had to spend huge amounts on the development of a piece of software, but distributing that software once you’ve made it is relatively cheap (eg, because people can just download it), your markups will be high even though your profitability may not be. Digital markets do tend to have relatively high fixed costs, and as other sectors become more “digitalised” their share of fixed costs is rising too.

This appears to be the case in the United States, where apparently rising markups mostly disappear when you include fixed costs like R&D, marketing, and management in the measure. The CMA looks at two measures of profitability to test this — earnings before interest and taxes, and return on capital employed — and finds profits basically stable over the past decade. So this may be true for the UK as well.

Another reason markups may be rising is that firms are innovating more and profiting because of it. Firms should make unusually high profits if they develop a better product, and we cannot assume that sustained profits in this scenario are a problem — after all, some companies may be consistently better at innovating than others, and we give legal monopolies to many innovations (in the form of patent protections) in part to allow their inventors to profit from them without their ideas being copied. Profitability for Covid vaccine developers Pfizer and Moderna will probably be higher next year — but that’s not a sign of weak competition!

One study of the United States’s manufacturing sector found that higher profits were associated with higher productivity, suggesting that the effect here is not weak competition but businesses profiting from improvements in their productivity.

Dynamism

All these are reasons to be cautious before assuming rising concentration or rising markups are necessarily signs of weaker competition, or that the opposite would be signs of stronger competition.

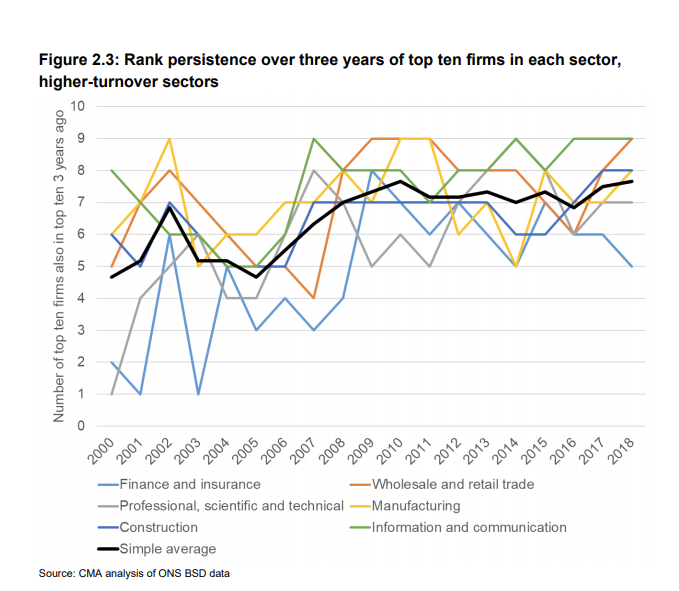

Most interesting are the CMA’s measures of dynamism, which look at persistence of firms at the top of the market, and the rates of entry and exit of new and old firms from the market. Other things being equal, we would expect that competitive markets are ones where large firms can be easily displaced by more productive new entrants, and that markets where the same firms have persisted for a long time may be experiencing weaker competition than we would like.

Most measures the CMA uses are basically unchanged — rates of firm entry and exit have not changed much since the 1990s, for example. But the likelihood of the top firms in an industry staying at the top has increased, as the black line in the chart above shows. This might be a sign of reduced dynamism, but it might just as easily be a sign of successful companies effectively fending off new entrants by improving their products. It is difficult to draw strong conclusions, especially given that randomness will drive some of the movement in this measure.

The structure of competition in Britain

Overall, the CMA paints a fairly benign picture, even if we interpret its measures naively, assuming that more concentration and profitability mean weaker competition. But what the CMA does not do is point to the structural factors in the economy that may be holding back competition — things like land-use planning, access to labour and capital for startups, and regulation in some sectors of the economy.

For example, one barrier to competition in the supermarkets sector is likely the difficulty that supermarkets face in getting permission to set up new stores. If land-use planning is preventing Aldi or Lidl from competing with incumbents in some places, that is a serious barrier to entry that is largely being ignored. This also hurts smaller, independent retailers, according to one study.

Startups that cannot access the employees they need (say, because they cannot get work visas for them) or raise enough capital will not be able to compete effectively with incumbents. Access to investment may be being limited by regulations about how institutional investors can use their funds. The Entrepreneurs Network highlighted one striking statistic: pension funds contribute 65% of venture capital funds in the US, but only 12% in the UK. If dynamism in the UK is weaker than we would like, this would seem like an area to explore.

Regulated sectors, like energy and finance, have both enormous, overgrown regulators (which often have contradictory statutory objectives, only a few of which relate to competition and consumer welfare) and weak competition enforcement.

The sector regulators like Ofcom and Ofgem have “concurrency” powers which make them, not the CMA, responsible for competition enforcement in their sectors — in practice, because these regulators have other priorities and have close relationships with industry incumbents, very few competition cases are ever brought. One solution may be to replace them with a cross-sector infrastructure regulator that mandates and oversees open access to monopoly infrastructure, and return competition powers to the CMA.

These kinds of consideration may have been outside the scope of the CMA’s report, but for us to really understand the state of competition we need to think about it as a process, rather than an event. That means looking at the conditions that competition takes place in, not just its outcomes as measured by things like profitability and market structure — and thinking like gardeners trying to create the right conditions for the economy to grow healthily, not like engineers who can design and fine-tune it at will.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.