Michael Barone, an influencial political analyst, recently wrote a column about how to encourage womens career prospects in the Washington Examiner. The column, which has been syndicated to numerous other American papers, explains that the progressive policies of Hillary Clinton aimed to end the wage gap would in fact make it larger. Barone writes:

“Hillary Clinton’s solutions for equalizing pay – ‘flexible scheduling, paid family leave and earned sick days’ — tend to encourage women to take time off from work, which in turn tends toward lower lifetime earnings. That’s certainly been the effect in Scandinavia, where such policies have been carried farthest. The effect, Swedish scholar Nima Sanandaji writes, is that ‘many women work, but seldom in the private sector and seldom enough hours to reach the top.’”

Barone is pointing out a fact I would like to examine in greater detail in this column: time matters.

One way of examining this is to compare the Nordic countries (progressive societies with generous welfare states) with their Baltic neighbors (conservative cultures coupled with low tax models).

Around the world women on average earn less than men. In the political debate, we are often given the impression that at least part of the gender wage gap cannot be explained by real world factors. Instead, it is simply a result of gender discrimination. Hillary Clinton has for example said “there’s no discount for being a woman. Groceries don’t cost us less, rent doesn’t cost us less, so why should we be paid less?”. Indeed, why arbitrarily pay women less? Would any business owner inclined to create a successful enterprise rather than oppressing women really choose to do so?

However, what the same politicians seldom tell us is that there is a major real world factor which can explain much of the gender wage gap, and indeed the overall gap in career prospects between men and women: time usage. And what is odd is that the trend seen in progressive policies, such as those proposed by Hillary Clinton and those existing in the Nordics, are often focused on encouraging women to work fewer rather than more hours.

Women tend to take greater responsibility for household chores and children, having less time to invest in pursuing their careers. Marriage and family formation therefore hinders women’s career advancement. This explains why women on average lag behind men in terms of career at the ages where family formation is common.

If we take family out of the equation, the gender wage gap looks very different from how it currently does. Warren Farrell has isolated the effect of family and children by looking at the incomes for Americans with a higher education who have no children, work full-time, are in the ages 40 to 64 and have never married. This is the share of the population who have not, and are likely not either planning to, start families – instead devoting their time to careers. Farrell finds that the yearly incomes for women amongst this group is $47.000, considerably more than $40.000 for the men.

Large welfare states – such as the ones in the Nordics – are interesting in this regard. The reason is that their economic systems are based on a large proportion of women working part-time, often in public sector monopolies. Benefits and insurances in these countries are linked to having a job, which encourages both spouses to work. High marginal taxes at the same time create a situation where it makes sense for at least one parent to work part-time, and spend the remainder of their time on household chores. Also, the option to buy personal services are limited by high taxes. This reduces the incentives for both spouses to work full-time, since this increases the need to buy personal services that alleviate household chores. The Nordic system thus encourages women to work, but often part-time.

The Baltics are equally interesting since they are more conservative and family-oriented societies. The public sector offers less aid through subsidized childcare for example. However, low taxes and family bonds create a situation where working parents can either purchase personal services to alleviate household chores or alternatively ask relatives for help. Having support from close family members in the household is common in the conservative Baltic societies, but not so in the individualistic Nordic societies. The Baltic model creates stronger incentives for full-time work amongst women.

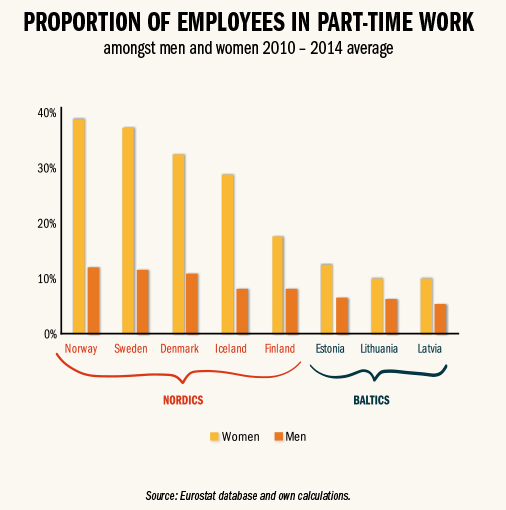

As shown above, part-time work is quite uncommon in the Baltics. Around one in twenty of the men and one in ten of the women in the Baltic countries work part-time rather than full-time. In the Nordics the proportion is about one in ten amongst the men. Amongst women however, part-time work is quite prevalent. The proportion of employed women working part-time ranges from 18 per cent in Finland to 39 per cent in Norway.

This, surely, has a significant impact on women’s progress. Individuals who reach the top very seldom work part-time. Rather, as Malcolm Gladwell has explained in the popular book Outliers: The Story of Success, those who attain great careers often do so after having invested an unusually high amount of time mastering a certain profession. Many women in the Nordics are in effect not competing for top positions, since they are working too few hours. In the Baltics a larger proportion of women are able to invest the time necessary to compete for top jobs. This simple observation can in part explain why egalitarian Nordic societies have few women at the top and – as shown below – why their small-government and more conservative neighbours in the Baltics perform better.

Women in the Nordic countries invest far less time in their careers as compared to women in the Baltics. The average employed man in Norway works fully 27 per cent more hours than the average employed woman. In Estonia and Latvia the difference is merely 7 per cent. The systematic difference between Nordic and Baltic countries, shown below, of course has a major impact on women’s success. A similar situation exists for business-owners. In Denmark men who own businesses work on average 19 per cent more hours than women business owners. In Latvia the difference is only 7 per cent. Looking at the average data for all Nordic and Baltic countries, it becomes clear that the gender time-gap is roughly twice as high in the former region for both the self-employed and the employees. It would be surprising if this did not have a significant effect on women’s progress.

So what do we see when we compare the Nordic countries – arguably the most gender equal countries on the planet in many regards, with large welfare states – with their Baltic neighbors – which have more conservative, family oriented, cultures with smaller governments? We see that the gap in working time is much higher in the Nordics. This is exactly what we should expect, since Nordic-style social democracy encourages women to work relatively few hours.

And what happens when policies encourage women to work less hours than men? The simple answer is that women fall behind men in their careers. Of course, there is a case to be made for progressive policies – such as government paying for family leave and earned sick days – but the case is not that it will encourage women’s careers. This is a lesson worth learning from the Nordic countries and their neighbors on the other side of the Baltic sea.