Liam Byrne tells us today that in order to “end the growing chasm of inequality”, we should rewrite the rules of economics. But that’s not something we get to do. We can no more keep spending when there’s no money left than we can rewrite Newton and fly to the Moon by flapping our arms.

The rules of economics are what they are. Our task is to understand them and then work within them, to pursue the goals we desire. It is thus our understanding which needs attention.

In his article, announcing the launch of a new “all-party group” manned by the usual “leading thinkers”, Byrne cites the work of “leading economists, such as Robert Reich, Joseph Stiglitz and Jason Furman” – as well, inevitably, as Thomas Piketty – who “have shown categorically that the rules by which current economic policy is made are simply not delivering private job creation, rising wages or the taxes needed for a flourishing society”.

What we need, says Byrne, is “to launch a new kind of debate in the hope of finding a new kind of consensus. The sooner we find it, the sooner we can reject once and for all the tired and increasingly flawed orthodoxy of shareholder value and trickle-down economics that took shape with such force nearly 50 years ago”.

Well, if we are to try to rewrite the rules of economics, then a good starting point would be to avoid the category error of declaring Robert Reich to be an economist. Paul Krugman usefully punctured that idea two decades ago. Nor should we listen too much to Joe Stiglitz, given his praise for Venezuelan economics.

And if we are to listen to Piketty, then we should do him the courtesy of getting what he says correct. Which is not that only the asset-rich are benefiting in the current economy, but that he worries that this might become true.

As Krugman again points out, it is still wage income that is currently playing the leading part in driving inequality, not imbalances in capital. And as Piketty’s own collaborators, Saez and Zucman, have pointed out, the rise in the importance of capital in the economy more generally is to do with housing equity and pension savings. Neither of which is the source nor result of plutocratic fortunes.

Or, to put it another way, we are not living in the world Byrne thinks we are – because he has not understood his own sources. Which makes him exceedingly unlikely to produce useful suggestions for what we should do next.

But actually, it is worse than that. For Byrne also entirely misunderstands the basic root stock of our economy.

Consider again that sentence about the need for a “new kind of consensus”: “The sooner we find it, the sooner we can reject once and for all the tired and increasingly flawed orthodoxy of shareholder value and trickle-down economics that took shape with such force nearly 50 years ago.”

The problem is that the only time anyone within economics takes trickle-down seriously is when we’re talking about technology. But then we should take it very seriously indeed.

As has been remarked: Queen Elizabeth I had stockings, it was capitalism and the Industrial Revolution that provided them to the mill girl.

In our own times, at the start of my working life, one minute of airtime on a mobile phone cost an hour of low-end wages. Today, you can buy the most basic Android phone for the equivalent of a couple of hours of minimum-wage labour. Which is important, because we know very well that 10 per cent of the population having a mobile phone in a poor country raises GDP growth by 0.5 per cent. We even know why. too. Also that cutthroat shareholder capitalism significantly increases market penetration.

Which leads us to the basic root stock, the rules, of our economy. Increasing income, and/or wealth, is driven by technological advances that lead to greater productivity. And only societies which have had some at least modicum of that shareholder capitalism have ever had that trickle-down which drives the desired result.

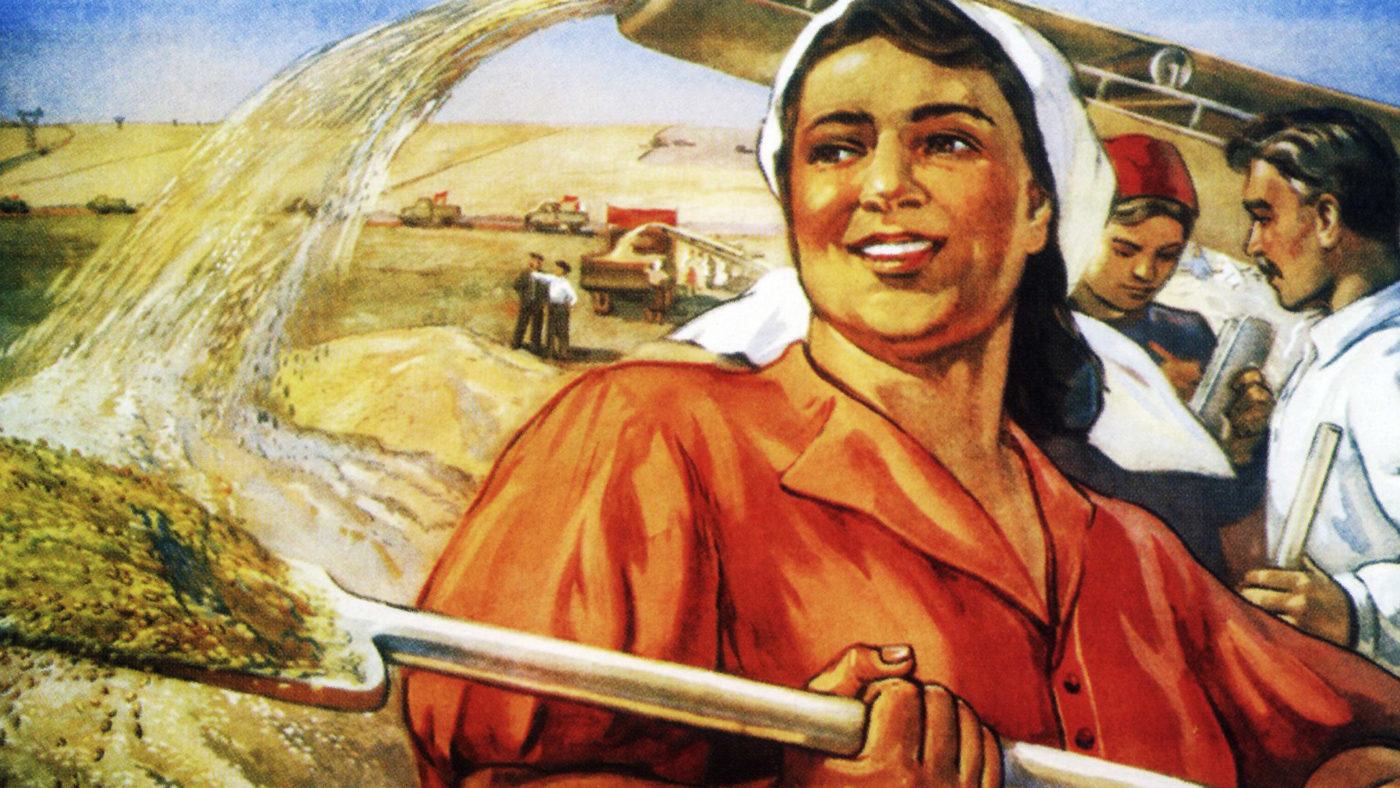

The Soviet Union managed to increase total factor productivity – the form of productivity increase which actually matters – not one whit in its 70 years. Roughly capitalist and roughly market economies crank it along at 1-2 per cent, year after decade.

Just a quick look around the world will show that places that have had shareholder capitalism for decades and more tend to be rich places. Places just getting it are getting richer – and those that don’t have it are still mired in peasant destitution.

This is not to say that our current economy is perfect, nor that we cannot make improvements to the structure. But we do have to understand the rules of economics to do so – the most fundamental of which is to acknowledge that it is this very capitalism, along with that trickle-down economics, which has dragged us all up from being peasants standing around in the mud.

Yes, we might want to modify some of the effects of that – as we do with tax and redistribution, for example. But we’ve still got to do that within the rules that the universe is dictating to us. The most essential of these being that only some rough variant of free-market capitalism has ever led to a sustained and substantial rise in the living standards of the average person. And however much arm-flapping we get from some spendthrift politico, that isn’t going to change.