Zimbabwe is back in the news. Or, it was. For about two days. European and Western media have dutifully reported on the series of painful economic crises the country has suffered since independence with the occasional “so-bad-it’s-funny” article on the birthday celebrations of the country’s long-time President Robert Mugabe. But the full tragedy is that the country is entering its second century of colonial rule, having enjoyed a 35 year stint of totalitarian independence in the middle, and no one seems to care.

I respect the points made in Augustine’s Chipungu’s article for CapX last month, yet can’t help but feel certain comments are missing some ugly truths. For example, it may be true that if “you divide the top 28 top country destinations for Chinese investment… the balance tips in favour of democratic societies such as Botswana and South Africa”. But this is largely irrelevant information if Chinese investment is actively preventing democracy from taking hold in other countries.

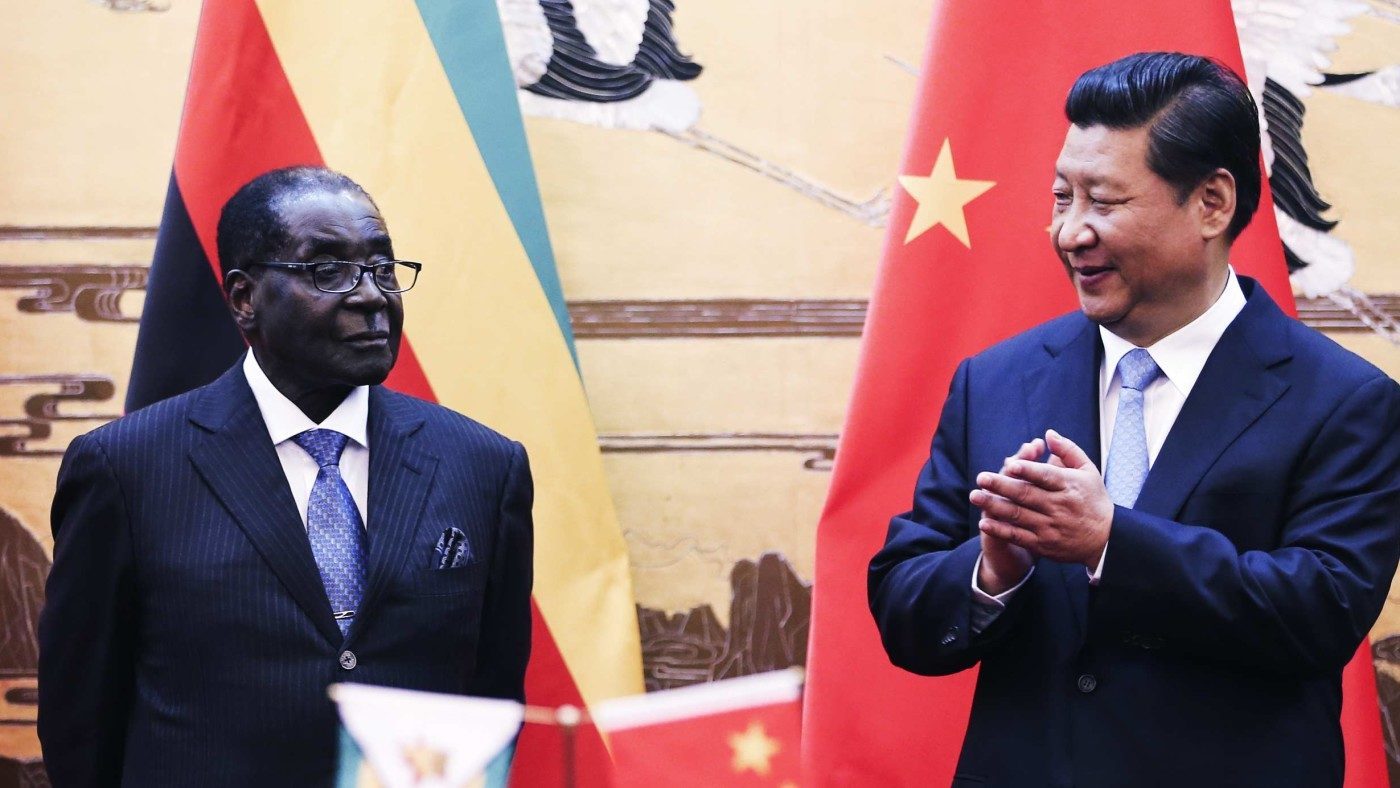

China’s presence in Zimbabwe is not new. However, the scale of infiltration may have been missed by Western media, or is being ignored.

Although formal diplomatic relations with China were only established on the 18th of April 1980, this friendship started from a shared ideological belief in Marxist-Leninism. Mugabe, whilst the exiled leader of Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU; later, ZANU-PF), his political party, explicitly stated that he wanted one branch of his guerilla army, ZANLA, to have a political orientation stemming from his supposed Marxist-Leninist philosophy. This alliance of ideas produced the notorious 5th Brigade, who were trained by Zimbabwe and China’s mutual ally, North Korea, and supplied with arms by Beijing. The depth of their ideological motivation can be measured by the fact ZANU turned against fellow revolutionary group ZAPU who were also socialist and funded by the Soviet Union.

Members of the 5th Brigade were active in Matabeleland to the West of Rhodesia, where they targeted Ndebele tribes who did not support Mugabe who is from a Shona tribal background. (Their main political tactic gukuruhundi roughly translates as “the early rain which washes away the chaff before the spring rains”.) This coercion and intimidation at the polls secured Mugabe an unexpected landslide victory in 1980: he won 62.99 per cent of the votes in the black elections. China’s role in this electoral success was not just acknowledged, but formally recognised in 2001 when it was given “Favoured Nation Status” by the government for helping it during the liberation struggle.

However, the relationship between the two countries truly peaked in October 2015. A private association of Chinese citizens based in Hong Kong, known as the Association of Chinese Indigenous Arts, awarded Robert Mugabe the Confucius Peace Prize. Why this secretive group, which has murky ties to the Chinese government, awarded the Chinese version of the Nobel Peace Prize to Mugabe remains unknown.

Since independence, China has invested heavily in Zimbabwe, despite European and World Bank sanctions. From 2000 to 2012, approximately 128 Chinese official development projects were identified in Zimbabwe. For example:

* Around US$144m has been pumped into Harare City Council for water infrastructure and sewerage rehabilitation.

* A multi-million dollar high-speed train service between Harare and Bulawayo was announced by China Railway Corporation in 2012.

* The Matabeleland Zambezi Water Pipeline project has been contracted by China Dalian Technical Group, and China has already budgeted US$864 million that will be extended through China’s Eximbank.

* Anhui Foreign Economic Construction (Group) Co. is close to completing the construction of a US$300 million 300-bed hotel adjacent to the National Sports Stadium, while an extra US$580 million has been pumped into a giant shopping mall.

* Tianze Tobacco Company, established in 2005 by China Tobacco Import & Export Corporation, has extended a cumulative $100m in interest-free loans to local tobacco farmers and controls over 72% of the crop through contract farming. ( A nice alliance as Zimbabwe is the world’s 5th largest producer of tobacco, and 68% of Chinese men smoke.)

Despite this, Zimbabwe recorded a trade deficit of US$290.99 million in December of 2014. Between 1991 and 2014, the average trade deficit was US$422.44 million, reaching a crisis point of over US$5 billion in 2011.

After the violent land expropriations in 2000, symbolising the loss of the rule of law in Zimbabwe, GDP fell by about 26% in two years, and inflation was more than 600% by the beginning of 2004. This triggered the downward spiral. As legally defended property ceased to exist, economic activity decreased. The banking sector was disrupted as borrowing and entrepreneurial activity dropped because property titles couldn’t be offered to the banks as a collateral loan. Incentives to engage in entrepreneurial activities were eliminated and foreign investment flatlined. Agricultural production levels sharply dropped as commercial farmers fled, taking their knowledge of sophisticated farming practices to other countries. Zimbabwe’s dire economic performance was no secret.

Zimbabwe abandoned its own currency in 2009, making the South African rand and US dollar legal tender in the country. Since then it has also added the British pound. These moves failed to curtail inflation, and six months ago, Zimbabwe’s central bank announced that it was completely phasing out the local currency. After years of hyperinflation (peaking at 79.6 sextillion%) the Zimbabwean dollar had become virtually worthless. 250 trillion Zimbabwe dollars was worth just $1. To illustrate: one local woman took her wheelbarrow to the bank in Harare, the capital, in order to carry the amount of bills she would need to purchase anything. On her way back to her car she was robbed. Two young men seized the wheelbarrow, emptied the cash at her feet, and ran off with the wheelbarrow.

Where does China come on the scene? In a move that initially appears unnecessary considering the other currencies in place, Zimbabwe has just announced that it would adopt the Chinese yuan as an official currency.

The stated goal of using of the yuan is increasing bilateral trade, namely helping African countries export more to China. The first step, according to Zimbabwe’s finance minister Patrick Chinamasa, is that Chinese tourists would be allowed to pay for services in yuan. He claims that use of the yuan “will be a function of trade between China and Zimbabwe and acceptability with customers in Zimbabwe”. The yuan has not yet been approved for public transactions in the Zimbabwean market, which is currently dominated by the US dollar, but is due to be activated early this year.

Many see this as part of China’s has push to internationalize its currency. Late last month, the International Monetary Fund’s Executive Board voted in favor of acknowledging the yuan as one of the world’s top currencies. Therefore it is unclear why use of the yuan in Zimbabwe, a failing economy, should be a priority for China. The decision to make Chinese currency legal tender in Zimbabwe hints at a more sinister colonialist relationship.

The motives for Zimbabwe are also suspicious. Having China as an ally adds an ideological smokescreen, which has advantages both domestically and internationally. Revolutionary myths continue to serve the political function of mobilising domestic support, while close ties with China ward off criticism from Western states conscious of their colonial past. Unfortunately for Zimbabweans, Mugabe’s personal brand of socialism is limited to exploiting existing resources, with no plans regarding how to create wealth. The poverty-stricken nation has apparently learnt nothing from China’s rise. Instead, it has mismanged its way into impoverishment. From 1985 to 1987, agriculture contributed an average of 13% of Zimbabwe’s GDP and provided more than 90% of its food requirements. By 2013, in contrast, the World Food Programme estimated that 2.2 million people — equal to a quarter of the rural population — needed food assistance. If well managed, the country could cater for the whole continent. Instead, its people face starvation.

So China may seem an attractive benefactor. In November 2012, the Zimbabwean government received grain worth more than US$15 million from the Chinese government as a flat-out donation to prevent several communities disappearing to famine. Zimbabwe also desperately needs China to supply what little infrastructure it can hope for. The 2003 disagreement with the EU led to targeted sanctions, capital flight, and economic depression. Many Western leaders had hopes that this international pressure would cause the Mugabe regime to implode. It has not, but it has left Zimbabwe is in dire need of trading partners, with China there to fill the void.

Yet since then, Zimbabwe further isolated itself. In 2011, in a stunning case of irony, Zimbabwe central banker Gideon Gono made it clear he wished to avoid the US dollar as a transplant currency. He “warned that Zimbabwe’s nascent economic recovery is at the mercy of the United States dollar, which is facing new pressures from the Euro-zone debt crisis”, positioning Zimbabwe further from Western democracies.

It seems unlikely the move away from the dollar was truly out of fears over the Eurozone stability. Far more plausible is that Chinese pressure has coerced the government into distancing Zimbabwe from other global powers. Central Intelligence Organisation documents suggest that China continues to play a central role in retaining President Robert Mugabe in his political seat, finding that high level military officers work closely with the local army in poll strategies, while Beijing bankrolls Mugabe’s party. The construction of the new National Defence College in 2010 (to the tune of US$98 million, on loan from the China Export and Import Bank) strengthens these suspicions. Furthermore, the currency adoption is actually part of a deal in which Beijing will also cancel $40 million in debt. Zimbabwe is adopting the yuan because it is propped up by the yuan. It may have had little choice in the matter.

The yuan has indeed been making inroads elsewhere on the continent. Kenya and South Africa both host clearinghouses that enable traders to conduct transactions between local currencies and the yuan without going through the US dollar first. China’s expansive economic connections in Africa make the widespread introduction of the yuan on the continent a welcome development for them, and the myriad of weak currencies in the region only aids this aim.

But China is now Zimbabwe’s largest trading partner, and purchases 27.8% of the country’s exports. Murray & Roberts, a top construction firm in Zimbabwe have noted that the Chinese are also dominating Zimbabwe’s construction industry, taking the few projects on offer. According to their spokesperson: “The Chinese have also taken over the telecommunications industry and we face stiff competition because they have cheaper and more skilled labour. M&R is contemplating joining hands with Chinese construction firms, who have been given major projects in the region.”

Zimbabwe has witnessed an economic uptick in recent years (brought about, in part by rising commodity prices, as well as a diversification of foreign investment options) but these short-term gains can only thinly mask the danger Mugabe is putting Zimbabwe in. Adopting a foreign currency can put a lid on hyperinflation, but it’s very difficult to reverse the process. Zimbabwe is now entirely in the hands of the Chinese. If they cut off their oxygen supply to the Sub-Saharan nation, Zimbabweans will not have long to wait before their country gives up the ghost.