In his excellent guide to fiscal jargon for CapX, Duncan Simpson’s entry on “windfall” reads as follows:

When tax receipts are higher than was forecast, it is described as a “windfall”. This leads to conversations about how to spend the unexpected cash. But why is this “windfall” never used to bring down the deficit? Or to allow for a tax cut? Also: “wiggle room”, “finding money down the back of the sofa”, “headroom” or most absurdly a “war chest”.

In the end, Hammond did “find some money down the back of the sofa” and – unsurprisingly – he spent it.

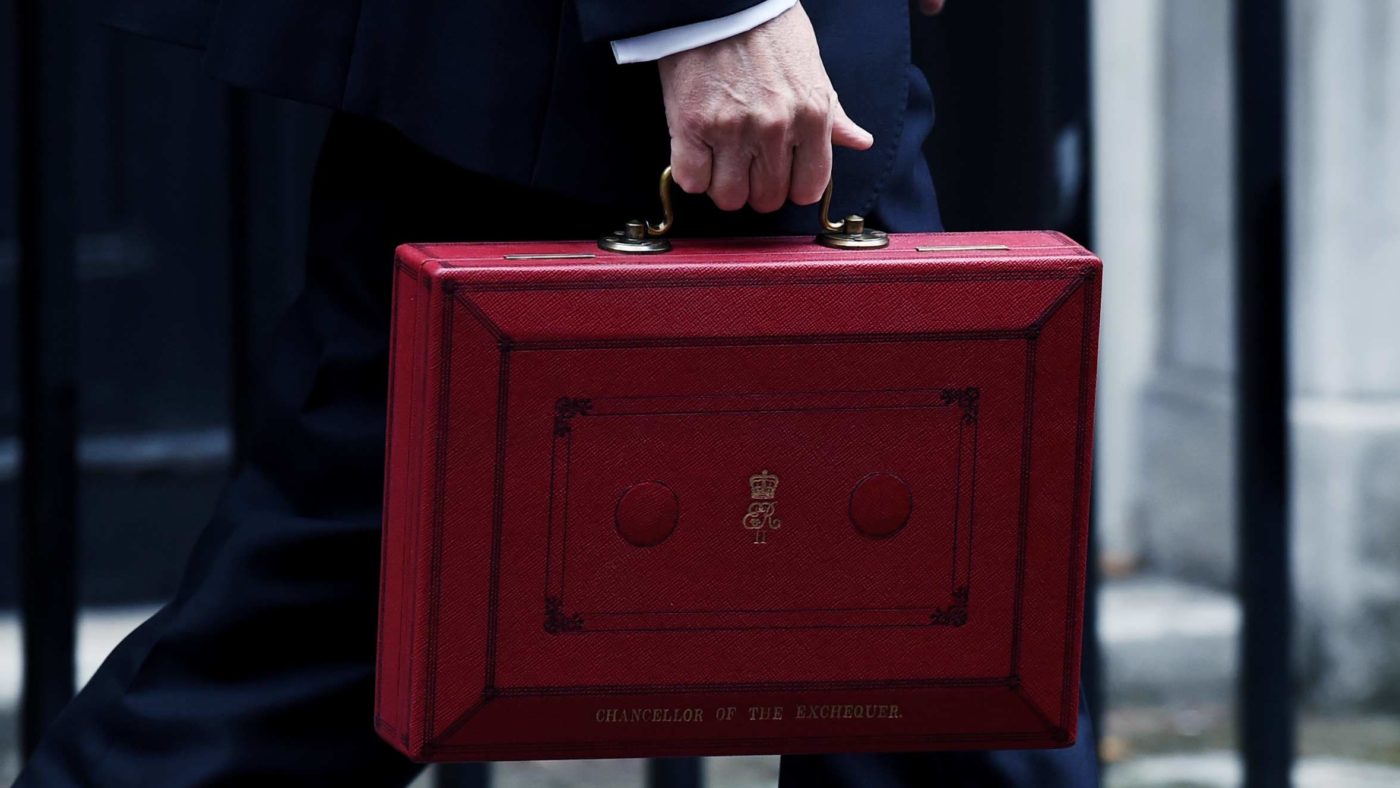

But, as today’s budget made clear, the biggest problem for anyone in Philip Hammond’s position isn’t a shortage of fiscal wiggle room. It’s the almost complete lack of political wiggle room.

Hammond stuck to his fiscal targets. But a budget won’t unravel because of gloomy macroeconomic numbers or a missed target on the government’s balance sheet. Rather, it is when he finds himself on the wrong side of a long and ever-growing list of untouchable interest groups and sacrosanct pledges that a chancellor lands himself in trouble. That is what happened to George Osborne when he dared to tax pasties in 2012. It is what happened to Philip Hammond when he dared to up the National Insurance contributions of the self-employed earlier this year.

Hammond has only dodged such a blunder this time because he has been so downright cautious. And when the list of fiscal no-go zones reaches a certain point, Britain can no longer be governed effectively. I fear we have reached that point.

There are good reasons for the government to make hard-and-fast fiscal rules for itself. For example, ringfencing specific departments’ budgets, as the Coalition did from 2010 onwards, might have made cuts harder to find in strictly fiscal terms. But it made them politically possible. It said to voters: we are tackling Labour profligacy but we are not totally heartless bastards.

But onto a few sensible promises, the Conservatives have tacked on a lot of silly ones over the years. The result is the emergence of a Tory fiscal dogma that makes very little economic sense.

The holiest and most incontrovertible of these rules is that the White Van Man is sacred. There is no one more honest, more hard-working and worthier of being helped by the government than a self-employed tradesman whose work requires an amount of equipment that means he must drive a van. Do anything to make his lot harder and you will be charred to a light crisp as a ritual sacrifice in the next morning’s tabloids. Hammond treated this holiest of holies with due reverence today by exempting White Vans from a tax hike on diesel. If your van is a different colour, tough luck.

There are other similarly inviolable commandments: give the NHS more money; don’t touch the winter fuel allowance; preserve the green belt; freeze fuel duty. The list goes on.

These giveaways are not cheap. The Government has stuck to the pledge on fuel since 2010 (presumably in no small part thanks to a lively campaign from the Sun); doing so has cost £46 billion – which is slightly more than the size of the deficit this year.

When government is deemed to have tilted too far in the favour of one particular group, the response is not to do away with the special treatment that group gets. Rather, the answer is always creating new groups that the government cannot cross. Take the gap between the treatment of the old and the young. Spending taxpayers’ money on a universal benefit for pensioners (the winter fuel allowance) is an absurd waste; means-testing it is the only sensible approach. But the politically sensible way to redress the balance is a bung to the young: the 18-30 railcard.

On the closely related and all-important issue of housing, the government appears to be entirely unserious about tackling the fundamental problem. Instead, with help to buy and today’s abolition of stamp duty for those getting onto the housing ladder, it is simply creating another sacrosanct group: the first-time buyers. As the IEA’s Julian Jessop argued on Free Exchange last week, if first-time buyers shouldn’t pay stamp duty – a proposal which, according to the OBR, will only help those who already own property – why should second-time buyers? They are very often young families feeling the pinch. Do they not deserve the government’s support?

It wouldn’t be entirely fair to blame Philip Hammond or Theresa May for this. Though they have hardly shown much willingness narrow the widening gap between good politics and good policy. But someone, at some point, will have to be brave enough to create the political headroom needed to solve the really serious problems that are holding Britain back.