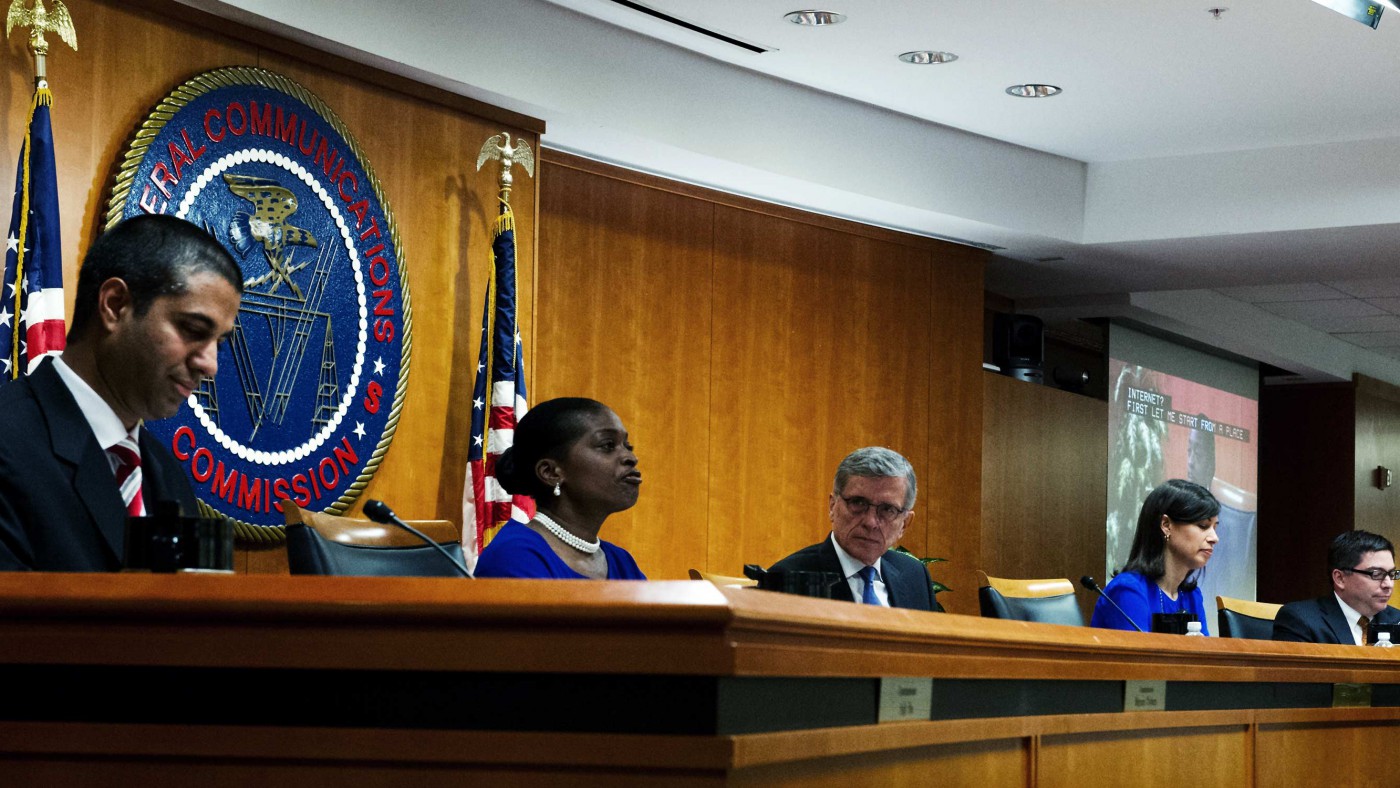

US Telecom v. FCC, a review of the Federal Communications Commission’s new network neutrality rules, will be argued today before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. The stakes are high for every American—and for our Constitution.

In autocratic countries like China and Iran, it is the government that decides which Internet content is permissible, and which must be censored. Individuals have no choice. Under the new network neutrality rules, which prohibit blocking, throttling, and paid prioritization, the FCC dictates to businesses offering broadband services which parts of the Internet they must offer—all of it.

At first blush, this might sound reasonable, and certainly preferable to the government censorship that pervades much of the world. But the First Amendment protects not only the right to speak without government interference but also the right to remain silent and the right not to be coerced into speech by the government. Nowhere is the right to be free from compelled speech more important than the Internet.

The FCC has undermined this right by claiming that broadband providers are mere conduits or “dumb pipes” for the speech of others—analogous to telephone companies—and therefore are not entitled to control the content on their networks under the First Amendment.

This position defies common sense and legal precedent. As petitioners in the US Telecom case argue, the mere fact of transmitting third parties’ speech does not cancel First Amendment rights. Twenty years ago, the Supreme Court held in Turner Broadcasting, that cable companies—also conduits for the speech of others—had a right, just like newspapers, to exercise editorial control over the content they transmitted. Like cable companies, and unlike telephone companies, broadband providers are purveyors of public communications and as such have an interest in exercising content control over their networks.

That broadband providers have customarily declined to engage in such control seems to have fed the idea that they lack such a right. However, the decision to refrain from content control is itself a form of editorial discretion. And broadband companies have largely chosen to treat content neutrally on account of consumer preferences for network neutrality, without the need for policing by the federal government.

But there are legitimate reasons why an Internet company would engage in content control, precisely in response to consumer preferences. While the Internet provides a marvel of valuable information and entertainment, it also comes with every form of vice imaginable: indecent material; websites that explain how to make a bomb; chat rooms with sordid purposes; and “lawful” websites used by criminal and terrorist groups like ISIS to spew venomous propaganda and recruit vulnerable individuals to their cause.

In a consumer-friendly world, we would select among different broadband providers, and choose the one that offered the best services to suit our needs. Such services might include blocking offensive sites or adapting content to target particular constituencies. Sites such as cleaninter.net and theJnet.com are examples of services that filter content to suit religious Christian and Jewish audiences.

But under the FCC’s new network neutrality rules, these and other filtering services if provided by a broadband company would be illegal. Rather than allow broadband providers the option of providing different degrees of filtering to reflect different consumer demands, the FCC requires that all content be treated the same.

In an America with network neutrality rules, purveyors of indecent material and groups such as ISIS have a right to enter American homes through the Internet, and consumers lack the corollary right to have their broadband providers kick them out. As long as a site is “lawful,” broadband providers are powerless under network neutrality rules to respond to consumer preferences by blocking it or even parts of it, or favoring other websites—all under the banner of “neutrality.”

The economically efficient and constitutional way to enable users to control internet content is by means of the free market, not government coercion. Insofar as the government deems it necessary to police the editorial points of view of broadband providers, network neutrality represents an illicit attempt to burden speech based on the nature of its source. Unlike the must-carry rules for cable at issue in Turner Broadcasting, which were designed to protect access to government-licensed free broadcast stations, and not to privilege or undermine particular content, network neutrality is precisely designed to censor broadband providers’ content choices. We must not be deceived into assuming that because a regulation contains “neutrality” in its name, that it is therefore content-neutral for First Amendment purposes.

Nor can network neutrality be flipped on its head and justified on the grounds that promoting neutrality is in the interest of the First Amendment. The Supreme Court has for decades rejected the argument that the First Amendment entitles speakers to a right of access to be heard. And the recent Citizens United decision reiterated that a government interest in equalizing the relative ability of speakers to be heard did not justify limits on speech.

Nowhere else in the world is freedom of speech protected to such an exceptional degree as in the United States. In an age where groups like ISIS seek to destroy our Constitution, we must take care not to trample on it ourselves. The unregulated Internet and America have prospered together over the past 25 years. Few are the complaints from Americans that broadband providers have blocked Internet content. The FCC’s new network neutrality rules are a big government solution in search of problem, with pernicious consequences for the First Amendment. The FCC has gone beyond the law. Consumers suffer. And purveyors of filth and groups such as ISIS celebrate.

The D.C. Circuit can and should correct the FCC’s mistakes.