It’s hard to think of a more dangerous manifestation of the dangers of fake news and disinformation than the re-emergence of measles across the Western world.

In the US alone there have already been six outbreaks of the disease in the first two months of this year, from New York to Washington State and Texas. In Europe more than 80,000 people contracted the disease last year, with 35 reported fatalities, triple the 2017 figure and more than 15 times the equivalent figure for 2016.

Among medical experts there is little doubt that the re-appearance of a disease which had been all but eradicated from many countries is down to doubts about vaccine safety.

Indeed, the World Health Organisation has listed vaccine hesitancy among its top 10 global health threats for 2019, along with Ebola and the Dengue virus.

Unsubstantiated claims about the efficacy and safety of vaccines are no longer the preserve of online conspiracy cranks and ‘natural medicine’ quacks. Along with long-time celebrity allies such as Jim Carrey and Robert de Niro, vaccine deniers now have friends in high places: Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen and Italy’s deputy prime minister, Matteo Salvini have all raised doubts about one of the most successful medical interventions in human history.

Vaccination has even become a front in the information war between the Kremlin and the West, with Russian bots starting up artificial online arguments to perpetuate confusion among the scared and credulous.

To many it will seem barely credible that such a manifestly successful innovation should be subject to such sustained attacks. But, no matter how overwhelming the evidence in their favour, it seems the case for vaccines needs to be made again.

And while the scientific consensus on vaccines themselves is well-established, the question of how to persuade the doubters is much less settled.

Cynthia Leifer, Professor of Immunology at Cornell University, says news outlets need to do much more to report the dangers of anti-vaccination material. She told CapX: “I am shocked and disappointed that there is not more media coverage of the fact that vaccine hesitancy is responsible for the rise in vaccine-preventable diseases. There is a direct correlation between falling vaccine rates and the rise of vaccine-preventable childhood diseases.”

One of the challenges is that there is no such thing as an ‘anti-vaccination movement’. While reporters may reach for the term as a convenient shorthand, anti-vaxxers are in reality a disparate group, with diverse reasons for refusing treatment.

They run the gamut from the outer fringes of the anti-government libertarian movement to conspiracy theorists, peddlers of pseudo-scientific remedies and parents convinced their children developed autism due to vaccinations.

The latter is a particularly prevalent belief, largely thanks to the repeatedly debunked claims of Andrew Wakefield. The former doctor was struck off by the UK’s General Medical Council in 2010 for “serious professional misconduct” over research claiming a link between the MMR vaccine and children developing autism. That has not stopped Wakefield, who continues to style himself as ‘Dr Wakefield’ on Twitter, from reinventing himself as a kind of anti-establishment truth-teller across the pond. He was even granted an audience with Trump on the campaign trail in 2016.

There are also differences in the nature of anti-vaxxers’ criticisms. Some accept that vaccines work, but think the side-effects are too risky, while others think they are both risky and ineffectual. The latter group usually explain the eradication of diseases such as smallpox and polio by arguing that infection rates were already declining before the introduction of innoculations.

Ironically, it is the very success of vaccines that has helped breed this kind of toxic complacency.

“One could say we are a victim of our own success,” says Professor Leifer. “Vaccines worked so well, society forgot. The result was we lost our fear of contracting childhood diseases. I call it societal amnesia. The problem is, these diseases are still around and if people choose to not vaccinate they will re-emerge. This is exactly what we are seeing with the resurgence of measles.”

As well as the outright deniers, there is another group – especially prevalent in US states such as Texas – who do not deny that vaccines are effective and safe, but who argue it is an infringement of personal liberty for the Government to force parents to accept a particular medical treatment.

“The problem in dealing with these things is the variety of anti-vaccine motivations and beliefs, it makes it very, very hard to address the issue in a global manner, [to find] a solution that fits all the different reasons to refuse vaccines,” says Dr Sebastian Dieguez, a researcher in neuroscience and cognitive psychology at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland.

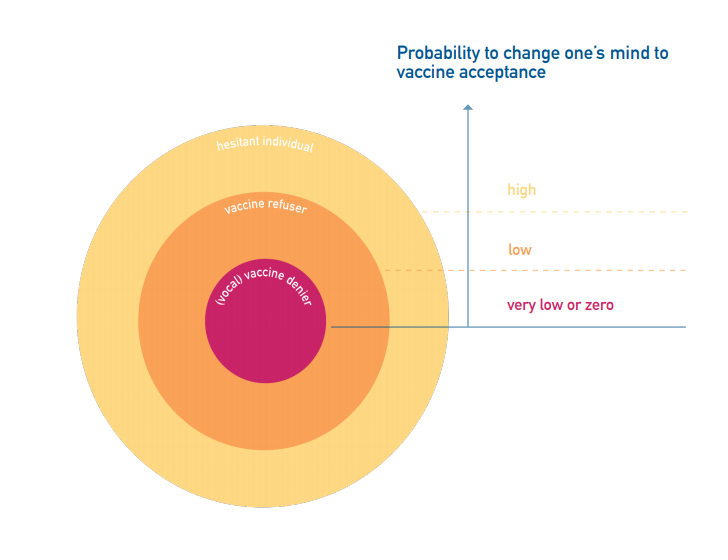

The WHO also makes a distinction between the hard core of “vaccine deniers”, who are small in number, a bigger group of “refusers” and a larger group still of those who are “hesitant”.

Interestingly the WHO’s guidelines to medical spokespeople suggest ignoring the most vocal anti-vaxxers, most of whom are impossible to sway, and communicating directly with the public.

Among those who helped formulate those guidelines was Dr Robert Bohm, a specialist in decision analysis at the University of Aachen. He has published extensively on how behavioural insights can improve the effectiveness of vaccination policy.

“What we are really trying to do is reduce [anti-vaxxers’] influence on other people who we would maybe call fence-sitters, people who have some scepticism and would like to have some more information,” Dr Bohm says.

It’s not just those who are hesitant who need to be kept informed. According to Dieguez, it is just as important to make sure those who do choose to vaccinate know why they are doing so.

“You also have to take into account the people who do vaccinate,” he says. “Many of them have a lot of misconceptions and don’t understand how it works and why they do it.”

That education turns people who are pro-vaccine into “effective ambassadors for their friends and relatives.”

Perhaps surprisingly, Cynthia Leifer says scientists themselves are among the worst advocates for vaccines: “Scientists are doing a terrible job of addressing vaccine hesitancy. Scientists are trained to correct misconceptions with facts, but this is the worst approach to deal with vaccine hesitant parents.”

One way of avoiding difficult debates about persuasion strategies is simply to enforce prescription of vaccines by fining those who refuse to immunise their children. This was the approach adopted in California, where the state government passed a law in 2016 making it compulsory to vaccinate schoolchildren against diseases including measles, chicken pox and rubella.

For Leifer this is simply a matter of pragmatism. In her view, although persuasion is certainly preferable, legislation may be the blunt tool needed to save lives

“It is unacceptable that children are dying from diseases we can prevent with safe and effective vaccines,” she says.

“I’m sure mandates will met with resistance due to threats to civil liberty, but what are we to do when parents are making risky choices based on misinformation?”

While mandating has the advantage of simplicity, it fails to deal with the root causes of vaccine scepticism. And forcing people to submit to a particular medical intervention risks reinforcing resistance and bolstering the arguments of those who claim vaccinations are part of a sinister government conspiracy.

Social media firms are a major front in the vaccines war – and one where there have been positive signs of late. The image-sharing site Pinterest has taken a lead by simply blocking all searches containing the word “vaccination”. YouTube has not removed anti-vaxxer videos, but it has at least stopped them making money through advertising on the site.

As for Facebook, the firm has yet to take serious action, though it has recently indicated it will work to downgrade anti-vaccination material in users’ newsfeeds. On the face of it, theirs is a Herculean task, with tens of thousands of false claims posted every single day. However, analysis from The Atlantic’s Alexis Madrigal shows that a handful of users are behind a huge proportion of the most viewed posts on the site.

While a combination of legislative action and activism from big tech firms will undoubtedly help stem the flow of misinformation, there will still be a sizeable number of people who need to be talked around to the virtues of vaccination.

Though public health experts are agreed on the importance of education, there does not appear to be a consensus on the best strategy to overcome scepticism.

A study led by University of Illinois psychologist Zachary Horne concluded that warnings about diseases, coupled with anecdotes and pictures of sick children are a good way to counter anti-vaccination attitudes.

In a similar vein, University of Oxford’s Vaccine Information Project has a ‘Stories’ section featuring videos of people explaining the ill-effects of various illnesses, from cervical cancer to measles.

However, Robert Bohm disputes the idea that campaigns based on fear are an effective way to convince doubters. The German academic says such a ploy could end up reinforcing some people’s refusal to engage with medical advice.

“I’m a bit sceptical working with too much fear, we rather work with positive things like pro-social traits that we try to increase, you can protect yourself and your children but also other people who may not be able to help themselves,” he says

According to Bohm, the latter message about social solidarity has proven particularly effective in Western countries.

“We’ve shown that if we communicate that vaccination is actually really important from the societal level, then people change their mindset and become more positive,” he says, though he adds that “in Asian countries, where people are more collectivist this is more a default thinking mode and if we communicate it, it doesn’t change much”.

Those kind of cultural differences are an area he says needs “much more research” in order to formulate country-specific strategies. That applies not just to very different cultures, but to relatively similar countries. Vaccination rates are significantly higher in the UK, for instance, than in France and Italy.

One promising strategy is for medical staff to conduct ‘motivated interviews’, a technique first developed in the 1980s to help people with addiction problems. Rather than simply bombard parents with facts, MI involves doctors leading them through a series of questions, examining their doubts in a sympathetic fashion so that they feel informed and listened to.

Though there have not yet been conclusive large-scale studies on the effectiveness of MI, a paper from a team of Canadian researchers noted a “significant increase in vaccine knowledge and in readiness to receive vaccines”. The same team have developed a new educational approach called PromoVac, where specially trained nurses sit down with new parents for 15-20 minutes to discuss how they feel about vaccinating their baby.

And while recent outbreaks of childhood diseases are certainly cause for concern, Bohm strikes a remarkably positive note about winning the battle against disinformation: “In the last 10 years there’s much more research, great new interventions, great campaigns and I’m very optimistic, in principle I’m optimistic that the interventions will help the people to make the right decision.”

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.