It is time to start paying attention to the Liberal Democrats again. After nearly a decade of electoral drubbings, they show strong signs of recovery. In the local elections in May the party ended up with a net gain of over 700 councillors. That goes some way to rebuilding the “pavement politics” network which they once quietly thrived on. In the European Elections they got a higher vote share than Labour or the Conservatives and won 17 seats — the last time round they returned a solitary MEP.

When it comes to their prospects at the next General Election, the most recent opinion poll I could find (for IpsosMORI) had them on 22 per cent. That was behind the two main parties (if they can still be described that way) — but not by much.

From a pro-market perspective, the party has certain attractions. There is the classical liberal, free-trade tradition from the 19th century. At their best, the Lib Dems are the heirs to William Gladstone. He favoured low taxation on the grounds that the state would spend extravagantly and so it was a better idea to let money “fructify in the pockets of the people”. The Lib Dems can also trace themselves back to the Manchester Liberals, Richard Cobden and John Bright, the founders of the Anti-Corn Law League.

It is true that much of that heritage was betrayed over the past century as the Liberal Party sought to position itself as the centre party — thus in the middle of the mushy, statist consensus. The merger with the SDP confirmed that. Yet even in our own time there has been some pleasant surprises.

In 2004, a collection of essays called the Orange Book was published. David Laws, at the time a Lib Dem MP, proposed a compulsory “national health insurance scheme” which would require everyone to sign up either with the NHS or another insurance provider. He argued that increasing choice will still provide free health care at the point of demand. Laws suggested we could learn from arrangements on the continent and have “better health outcomes” than from the NHS “monopoly”. How many Tory MPs would have dared come out with this stuff?

Then during the Coalition Government from 2010 to 2015 rather than stasis, we saw some pretty bold reforms — most notably on welfare and education. There was also greater localism — a process that the Lib Dems not merely acquiesced to but encouraged.

Nick Clegg declared: “Opponents of localism brandish the phrase ‘postcode lottery’ to dramatize differences in provision between areas. But it is not a lottery when decisions about provision are made by people who can be held to democratic account. That is not a postcode lottery — it is a postcode democracy.”

Those of us who have attended Lib Dem conferences recognise a distinct tribe. Scruffy and eccentric, it is easy to see why some voters regard them as a bunch of hippies rather than a Government in waiting.

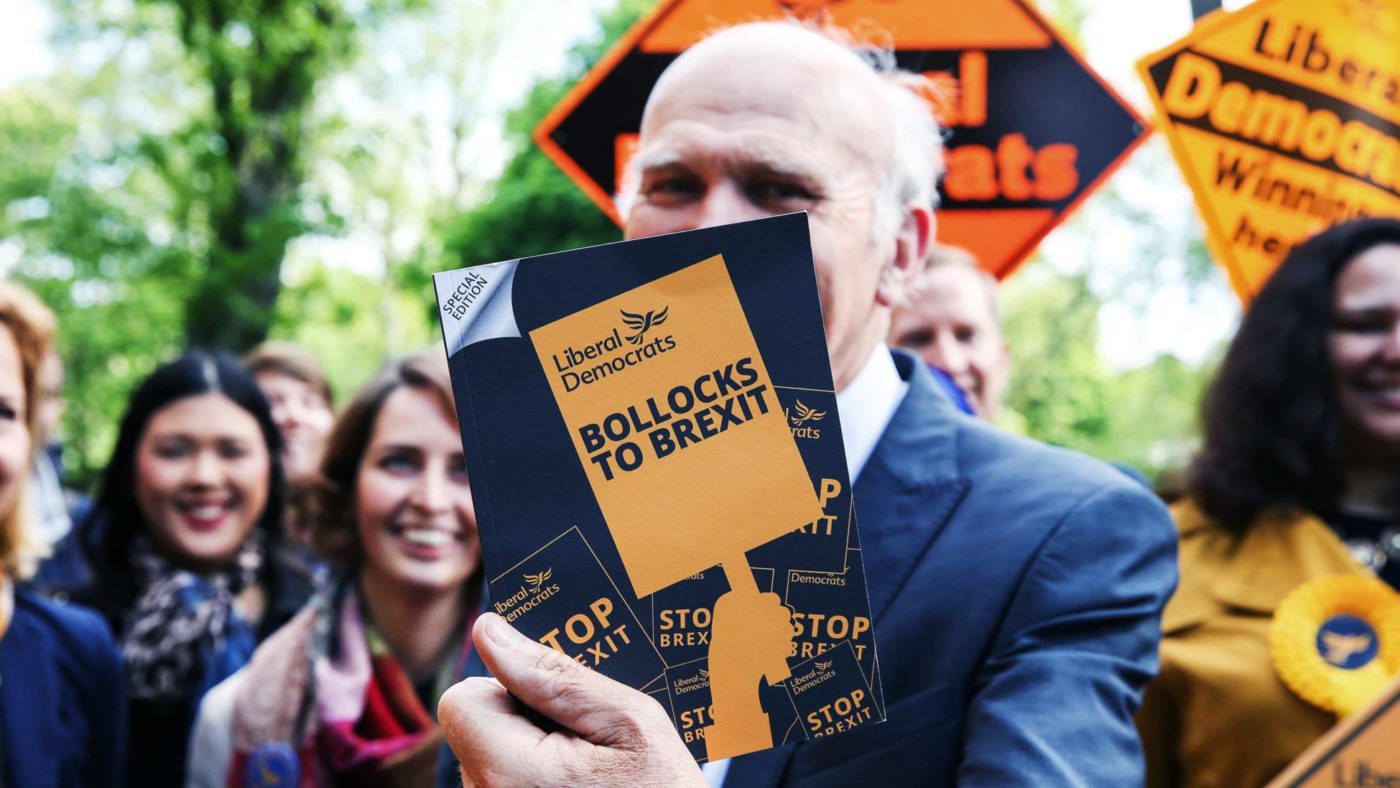

Now the party finds itself in the midst of the “other leadership election”. Sir Vince Cable is standing down. Two Lib Dem MP — Jo Swinson and Sir Ed Davey — are competing to succeed him. The winner will be declared on July 23, just after the new Conservative leader is announced.

It might seem like fortunate timing for the new Lib Dem leader. The reason, of course, is their clarity in opposing Brexit — and that being the issue that overwhelms normal party allegiance.

Remainers (often young, middle-class and metropolitan) who would previously have voted Labour wish to punish their Party for its equivocation under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership. Fine and dandy for the Lib Dems if we have an early General Election. They will also be well placed if due to machinations in Westminster or Brussels, the interminable delay in resolving the question of our EU membership drifts on with no prospect of being resolved.

But if we do leave on October 31, and the next General Election does not take place for some time, then being anti-Brexit will not be enough. They could have a policy that we should rejoin the EU — which would include a requirement to abolish the pound and use the Euro as currency. However that would surely all but the most hardline EU enthusiasts. Will there really be an appetite to reopen the issue so soon?

Given the other leadership election going on at the moment, Swinson and Davey can hardly be blamed for the limited media interest in their pronouncements. But visiting their websites is not a rewarding experience. There is a lack of policy substance beyond “stopping Brexit”.

Davey has a “vision” about defeating the “climate emergency”. But there they have to compete with the Green Party. Davey’s “economic plan” is generalities about investment being a good thing. Swinson’s pitch is much the same. She also has a section on “vision”. It says she want to “build an economy that puts people and the planet first.” She discloses that “the tech revolution presents enormous opportunities for individuals, communities and the economy.”

Both candidates are in favour of change. But neither tell us what change.

The Lib Dems could well offer some distinct, liberal and radical policies — legalising drugs, for instance. However both their potential leaders seem weak and timid. Thus the party is likely to struggle if and when Brexit finally takes place.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.