The UK’s competition watchdog – the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) – has got itself in a pickle with its controversial decision to block Microsoft’s acquisition of Activision, a producer of console games such as Call of Duty.

The CMA concluded that there was an ‘expectation’ that it would significantly lessen future competition in the cloud gaming service market. Yet Activision does not license its games to cloud game streaming services, nor does it stream games itself. While the European Commission and 40 other competition authorities had concerns, they accepted Microsoft’s offer of a 10-year licence of Activision’s games to its rivals – an offer the CMA refused.

Until last week, the CMA could take some comfort in the US Federal Trade Commission also being intent on blocking the acquisition. Unfortunately for the CMA, a US court rejected its case as unsubstantiated and wrong, thereby contradicting the CMA’s basis for blocking the acquisition. This kicked away the remaining crutch supporting the CMA’s decision, which it will now most likely reverse.

How did the UK’s august competition regulator get into this position? Its revised merger assessment guidelines emphasise the importance of ‘dynamic competition’ when assessing proposed mergers. This would have suggested few concerns, since Microsoft and Activision were not rivals, and the product at the centre of the CMA’s decision did not exist.

In the last two years, the CMA has veered from a relaxed position regarding vertical and conglomerate digital mergers to one where any perceived concern, no matter how speculative, of reduced future competition will be sufficient grounds to block a merger.

The basis for this more aggressive anti-merger approach is the unsubstantiated claim that Big Tech has systematically engaged in killer acquisitions (i.e. bought potential future rivals during the formative stages of their growth). The evidence for this idea was one study of the pharma industry which has little relevance to the tech sector, yet has nonetheless exerted an outsized influence on regulators worldwide.

The CMA’s new worldview is the ‘precautionary principle’, which holds that any risk to future competition – no matter how remote, speculative and hypothetical – requires intervention if it appears to give Big Tech the ability to introduce new services. Instead of becoming a beacon of liberal antitrust, the CMA has decided to become a world leader in the interventionist regulation of big tech.

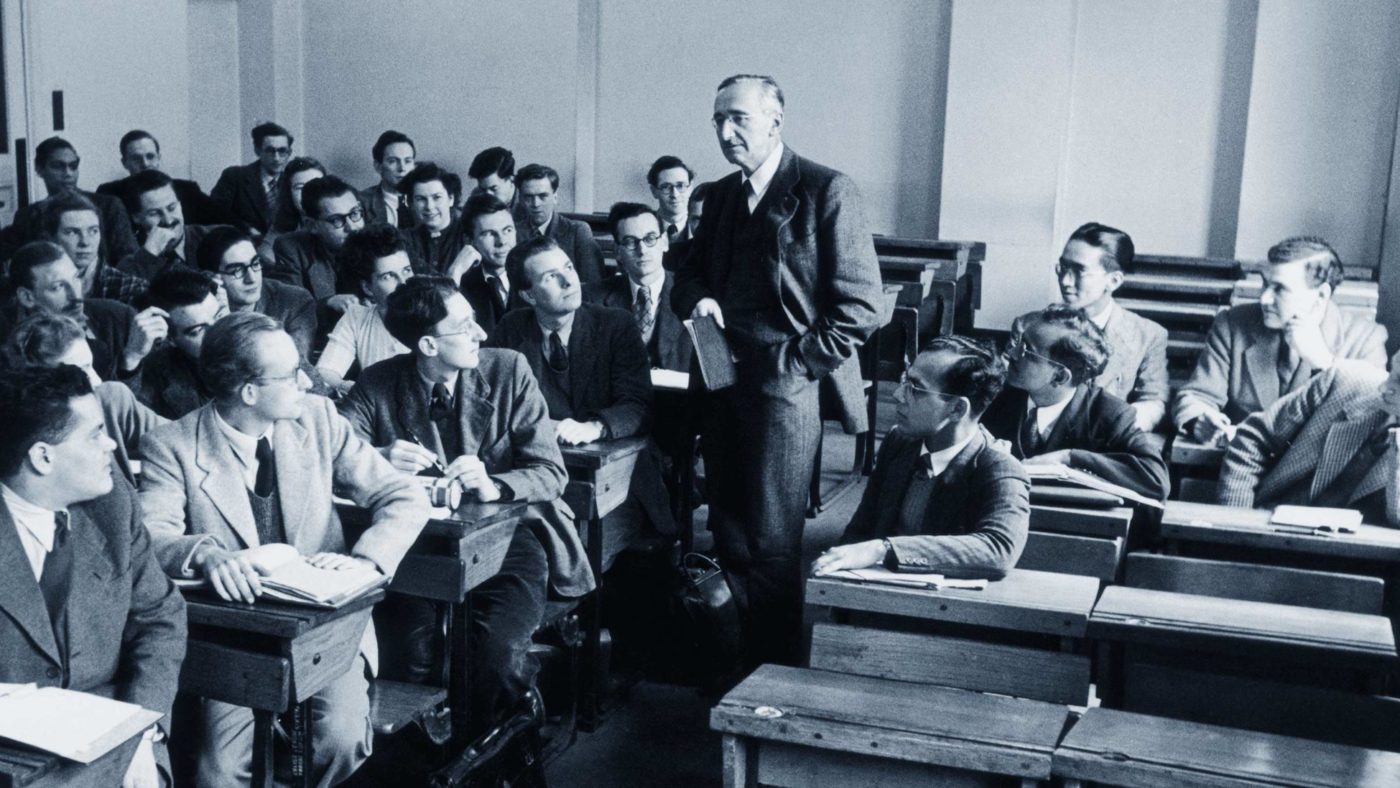

In these contested times for competition law, it is worth returning to first principles – in particular the views of the economist and political philosopher Friedrich von Hayek.

Hayek viewed the economy as a complex, dynamic, evolving system that could not even be fully known to technocrats, let alone directed by them. Big and small tech companies are not sleepy monopolists – they are dynamic and innovative, investing massive amounts into R&D, and generating huge consumer benefits. Their future is both unknown and unknowable. This alone should have humbled the CMA, and at least given it pause before ratcheting up its legal controls and questionable interventions.

Hayek died well before the internet and digital boom, but he did have a lot to say about the ‘big is bad’ mantra that has influenced the CMA and other competition regulators. According to Hayek, there can be no general rule about the desirable size of a firm. This is one of the ‘unknowns’ to be discovered by the market adapting to the ever-changing technological and economic conditions. Large firms are constantly challenged, both by rivals and by technology which disrupts their businesses and moderates their market power, even when the competition does not materialise or succeed.

As Hayek aptly put it, size itself is often the ‘most effective antidote to the power of size’, which one sees in the recent developments with Meta’s launch of Threads to rival Twitter. But the more worrying aspect of the ‘big is bad’ approach is its deceptive consistency with liberal thought. He also warned that the size and power of large firms most often ‘produces essentially antiliberal conclusions drawn from liberal premises’. But it’s worth noting that for Hayek, the issue was not ‘bigness’ per se, but ‘the ability of some monopolies to protect and preserve their position after the original cause of their superiority had disappeared’.

In my newly published IEA Hobart Paper ‘Hayek on Competition – Toward a Liberal Antirust?’, I set out Hayek’s approach to competition policy. To Hayek, free competition was the best guarantee of economic growth and individual liberty. Contrary to what some of his critics might claim, this did not mean untrammelled laissez-faire economics, but competition within a set of liberal laws which maintained a competitive economy (or ‘ordered liberty‘ as Mrs Thatcher once put it).

His pro-competition policies centred on removing government support for monopolies, restricting patent protection, reforming company law, and two competition rules – make restraints of trade unenforceable and outlaw exclusionary price discrimination by monopolies. These competition ‘rules’ would be enforced in the courts by giving those harmed the right to sue for multiple damages fuelled by contingency fees for lawyers.

This brings us back to the CMA’s decision to block Microsoft’s acquisition. The CMA has not only surprised competition lawyers, but its inability to provide a proper legal basis for reviewing its own decision has left the Competition Appeal Tribunal, which is hearing Microsoft’s appeal, unpersuaded and frustrated with the CMA. The CMA’s actions are hardly the Brexit dividend of better regulation one expected from disengaging from Brussels.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.