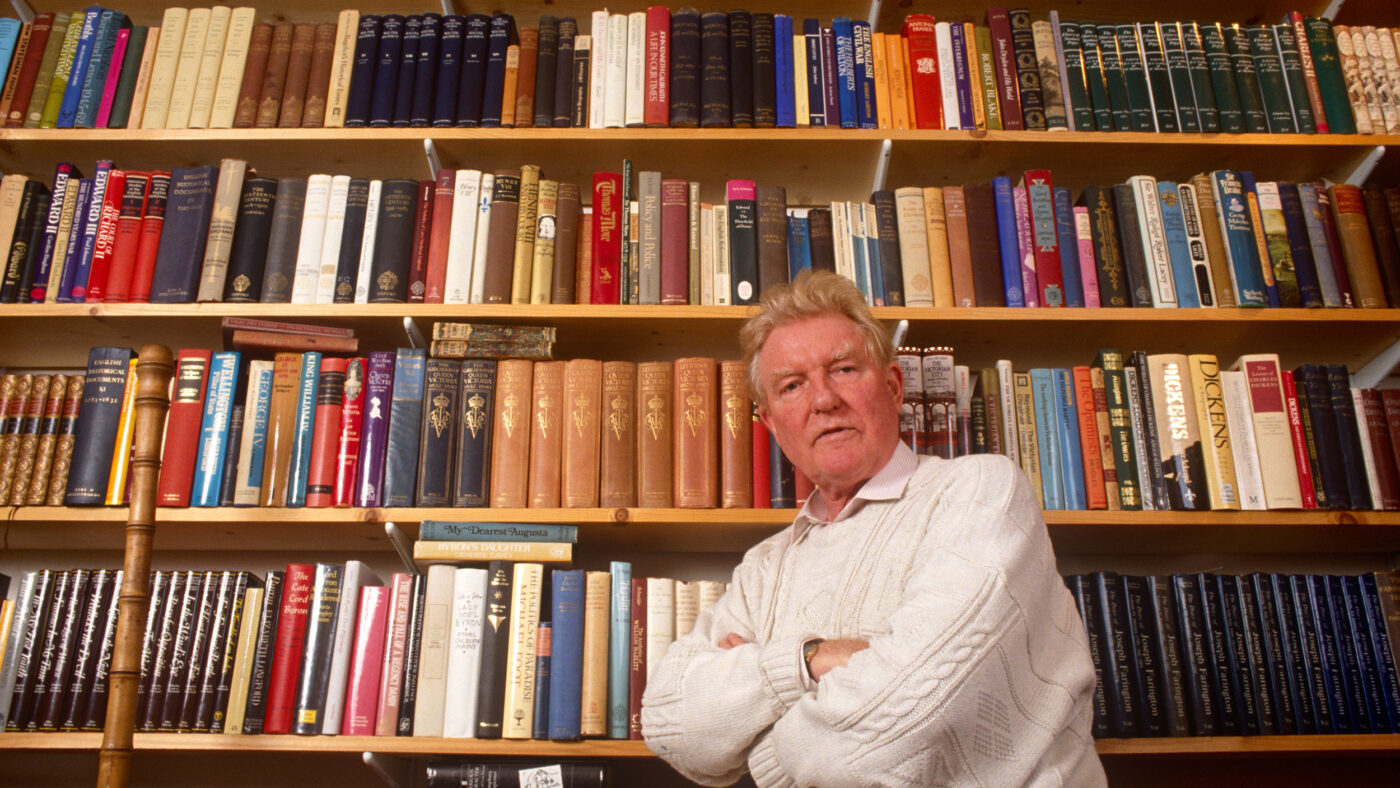

A rather ungracious obituary in The Guardian opens with the lines, ‘Many politicians and pundits abandoned socialism and the Labour party in the 1970s, but there were few rightward shifts of allegiance more dramatic than that of Paul Johnson’. Given the publication, it’s fair to assume this is meant to be a bad thing. But reading Johnson’s 1996 spring address to the Centre for Policy Studies, it’s clear that his conversion was a matter of conviction and a consequence of deep intellectual engagement with the history of conservative thought.

Paul Johnson began his career at The New Statesman as a close associate of Aneurin Bevan and a supporter of Harold Wilson. Then, in 1975, he published a denouncement of the ‘know nothings and half-wits’ of the trade union movement who had captured the Labour party – the more stinging for coming from a former friend.

By the time he gave the speech republished below as part of our ‘From the Archive’ series marking the 10th anniversary of CapX and the 50th of the CPS, he was an established – if always iconoclastic – commentator and historian.

‘What is a Conservative?’ explores the tensions between preservation and reform, pragmatism and opportunism, high principle and the will to power that have characterised governments from Pitt to Major. In the best conservative tradition, he resists ideological dogma. Instead he argues that conservatism is a human instinct – with all the paradoxes that humanity contains.

Those hoping for a clear, a succinet or a comprehensive answer to this question are doomed to disappointment. This is a historical inquiry and history teaches that there are many Conservatives and no such person as a typical one.

Before the Conservatives there were Tories, and they evolved during the English Civil War and Interregnum. The term ‘Tory’ comes from the Irish toiridhe, one who pursues, used in the Irish context to refer to the dispossessed native landowners who existed by plundering English settlers. It was extended to mean those with Popish sympathies or a willingness to tolerate Roman Catholics, and hence, during the reign of Charles Il, to Stuart loyalists who opposed the exclusion of the Catholic James, Duke of York, from the succession to the Crown.

Thus the term Tory came effectively into English usage during the 1680s and was used in conjunction with the name ‘Whig’, of Scottish origin, which originally signified the Lowland Scots rebels (of 1679) who opposed, for Nonconformist religious reasons, the Anglican Act of Uniformity of 1662. In the 1680s Whigs were, broadly, English politicians who sought to transfer powers from the Crown to Parliament. Both terms, therefore, were related to attitudes taken up towards the rights of the Crown and the nature of the religious settlement. The Tories held a view of the powers of the Crown not far short of the doctrine of the divine right of kings, and they defended Anglicanism as a national church which had the right to discriminate against those who did not belong to it, in the interests of social unity. The Whigs opposed both these attitudes.

Naturally, during the eighteenth century, by which time the two terms had become deeply established, men who thought about politics tried to trace them back into history. Dr Samuel Johnson laid it down: ‘The first Whig was the Devil, Sir!’; for him, the essence of Whiggism was rebellion against duly constituted authority, and the essence of Toryism was its instinctive defence. But if the Devil, as leader of the rebel angels, was the first Whig, then presumably God was the first Tory – and so He might be considered, in the sense that He laid down the laws of nature and the frame of government of the universe. On the other hand, God pre-existed His creation and might have left things as they were; by bringing the universe into existence, from a combination of love and curiosity – neither of them particularly Tory characteristics – He constituted Himself the primal innovator of history, and thus the dynamic originator of all change. That too might be thought un-Tory and certainly un-Conservative.

The origins of the Whig-Tory dichotomy can be traced to the reign of Richard Il at the end of the fourteenth century, with the King himself, who took an elevated view of the royal prerogative, speaking for the Tories, and John of Gaunt, with his notions of an ideally-constituted English community, speaking for the Whigs. Shakespeare, in his highly political play Richard Il, describes the conflicting attitudes brilliantly, from the standpoint of a sixteenth-century traditionalist. You could push the dichotomy further back, to King John’s conflict with his barons which produced Magna Carta in 1215. This might be described as the Ur-document of Whiggism; it has always been considered the first Statute of the Realm, the first Act (as it were) of Parliament to be inscribed permanently on the Statute Book. Since it went some way to circumscribe the powers of the Crown and assert the rights of the subject, it was distinctively Whiggish and anti-Tory.

The fortunes of the Whigs and Tories under William and Mary and Queen Anne are omitted from this pamphlet, because the final destruction of the Stuarts and the advent of the House of Hanover in 1714 introduced a discontinuity in English politics. Thereafter, for two generations, the country was governed by the Whigs. It was not exactly a one-party state but the mutations of politics were determined largely by factional struggles within the Whig Party, with the Tories as marginalised onlookers. The eventual return of Toryism to power was determined by a fundamental split in the Whig ranks.

The first Conservative Government in the modern sense was that formed by William Pitt the Younger on 19 December 1783. It continued to hold office, with minor interruptions and many changes of personnel, until 16 November 1830, when Earl Grey succeeded the Duke of Wellington as Prime Minister and introduced the first Reform Bill. During this half-century, something approaching our modern political system took shape and two sides formed which can be seen as the distant ancestors of our present Left-Right dichotomy.

There is a certain paradox in this account of the birth of Conservatism. Most people at the time would have called Pitt’s Government Whig, not Tory. He certainly thought of himself as a Whig, like his father, Lord Chatham, and he never called himself a Tory or allowed anyone else to do so. Edmund Burke, who became increasingly his ideological mentor in the 1780s and 1790s, always called himself a Whig, albeit he distinguished between New and Old Whigs. Yet by the time Pitt died in January 1806, his administration was unquestionably Tory and universally regarded as such.

Pitt, then, founded the Tory or Conservative Party as we know it, bringing forward an apostolic succession of young men like Jenkinson (Liverpool), Canning and Castlereagh. Sir Robert Peel gave his political heart to Pitt while still a schoolboy. It is impossible to imagine the Conservative Party, as a historical phenomenon, without Pitt. Yet it is not easy to see in what way Pitt was a Conservative. Virtually all his views favoured change. Chancellor of the Exchequer at 23, Prime Minister at 24, he was a young man who sponsored radical reform. All his early speeches, on which his reputation and career were made, reflected this. He supported independence for the American colonies. He backed ‘economic reform’ – that is, the abolition of ancient sinecures on which the eighteenth-century system of political corruption was based. He wanted to ban the slave trade and emancipate the Catholics. He advocated the end of pocket boroughs and the parliamentary representation of the new cities. In the early years of his Government he made himself a national hero by the honesty and integrity of his Government and his courage in standing up to, and defeating, the old Whig oligarchy, dominated by millionaire landowners. He reorganised the nation’s finances on a basis which promoted the industrialisation of Britain and he opened the era of free trade by an epoch-making commercial treaty with France.

Pitt’s elaborate and ambitious programme of ‘peace, retrenchment and reform’ – later, in the nineteenth century, to become a Liberal slogan – was overtaken by the outbreak of the long struggle against Revolutionary and Bonapartist France, which continued to the end of his life and beyond. He was obliged to organise and finance a series of monarchical coalitions against French republican imperialism. This cast him in the role of a reactionary archetype which fitted him ill. It is probably more just – and accurate – to see him as the defender of the constitutional principle, as opposed to revolutionary force. Bonaparte’s regime was Europe’s first police state, the prototype of the totalitarian systems which were to lock themselves on to Europe in the twentieth century, contemptuous alike of the liberty of the individual and the rule of international law. Bonaparte himself had a great deal in common with future dictators like Hitler and Stalin, and in opposing him, Pitt adumbrated the principle of freedom from aggression later personified by Winston Churchill.

Pitt, then, was a Conservative in the sense that he believed that evolutionary changes, conducted within the framework of an ancient constitution and through representative bodies like the House of Commons, were infinitely preferable to revolutionary changes detonated by violence. Changes should be brought about in an orderly manner, under the rule of law. International arrangements, likewise, should be negotiated within a framework of natural justice, codified if possible by treaty. But the changes to which he was committed were fundamental ones, to be introduced as and when convenient to the nation.

During and since Pitt’s day, the argument within Conservatism has been about the definition of ‘convenient’, which is largely a matter of timing. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Queen Victoria’s uncle, the Duke of Cambridge, who was Commander-in-Chief of the British army for 40 years (1856-1895), came to symbolise one end of the argument. Not an articulate man, he nonetheless summed it up well: ‘It is said I am against change. I am not against change. I am in favour of change in the right circumstances. And those circumstances are when it can no longer be resisted.’

At the other end of the spectrum was Pitt’s pupil, George Canning. He interpreted ‘convenient’ as the earliest possible moment at which changes could be put through with the support of public and parliamentary opinion, without danger to the rest of the constitutional fabric, and with a reasonable prospect that they would be workable, productive and permanent. Pitt’s most important successor, Robert Peel, hovered sometimes uneasily between these two definitions. As Home Secretary from 1822, he became the greatest legal reformer in our history, if we except medieval juridical innovators like Henry Il and Edward I. He transformed fundamentally the tripod on which the treatment of crime rests – the criminal code and its administration by judges, its enforcement by the police, and its punishment by prison. When he had finished, Britain had what is recognisably our modern system. On the other hand, in resisting, as head of the Tories in the Commons, the case for Catholic Emancipation, Peel came much closer to the Duke of Cambridge’s definition. He and the Duke of Wellington eventually surrendered their position, in 1829, only after Daniel O’Connell’s election for Clare, in the previous year, made its retention impossible. In 1830-32, Peel also opposed the Great Reform Bill almost to the bitter end and his surrender, in 1845-46, of the case against the repeal of the Corn Laws though graceful, timely and constructive, came only a short time after he had vehemently promised to retain them.

All the same, Peel enunciated in theory, and carried out in practice, the principle of making the best of the reforms of others, and this was to become one of the central axioms of British Conservatism. Once the Reform Bill was actually law, Peel rejected any resort to factional opposition to invalidate its working. He laid it down: ‘Recourse to faction, or temporary alliances with extreme opinions for the purposes of action, is not reconcilable with Conservative Opposition.’ It is notable that, in rejecting the cause of reaction, Peel for the first time used the word ‘Conservative’, a term coined by his friend John Wilson Croker. When the reformed parliament met, he wrote to Croker about his conduct in parliament in implementing the new regime: ‘We are making the Reform Bill work; we are falsifying our own predictions [of ruin); we are protecting the authors of the evil from the work of their own hands’. He followed this with a great speech as Leader of the Opposition in which he said that he had no great confidence in the Whig ministers, but he would support them whenever he conscientiously could. He had opposed the Reform Bill, though he had never been an enemy of gradual and temperate reform. But that struggle was past and done with, and he would look to the future ony. He would consider the Reform Act as final, and as the basis for the political system from now on. He was not against reform, as his record (when Home Secretary) proved. He was for reforming every institution which required it, but he was for doing it gradually, dispassionately and deliberately, that the reform might be lasting. What the country now needed was order and tranquillity, and he would take his stance in defence of law and order, enforced through the medium of the reformed House of Commons.

This speech was the direct precursor of Peel’s Tamworth Manifesto, addressed to his constituents in 1834, which carried the message of the Commons declaration to the wider audience of the nation. The Manifesto was approved by the Conservative cabinet which Peel had just formed. It pledged to maintain the Reform Act as the settlement of the constitutional question and the basis of political life; and Peel committed himself to a policy of moderate and steady reform. As the Tamworth Manifesto was the title deed of the nineteenth century Conservative Party, it is important to observe that the party thus born was for constitutional change, as Pitt’s had been. However, though Peel got his inner circle of supporters to endorse his Manifesto, it was never submitted to, or authorised by, all those interests and individuals whose backing was required to make the new Conservatism the majority party in parliament or the nation.

Peel’s relationship with the wider Conservative Party was thus always uneasy, though he was a masterful man and usually carried things with a high hand when in office. But it is significant that all his young followers whom he brought forward, such as Gladstone and Sidney Herbert, eventually found themselves outside the Conservative fold, as Peel himself did. Peel’s great Government of 1841-46 carried through an immense programme of moderate, practical and successful reforms, virtually all of which stood the test of time – thus he did indeed practise what he had preached in the Tamworth Manifesto – but on the emotional issue of the Corn Laws he could not carry his party with him. He lost the bulk of his followers in parliament, and still more in the nation, and they parted with bitterness. The Conservatives were then out of office, except for three brief episodes, until 1874 – almost an entire generation.

During this long spell in Opposition, and during the short intervals in office, 1852, 1858-59 and 1866-67, the party was re-fashioned by Disraeli, under the nominal authority of his chief, the Earl of Derby. Disraeli’s success in keeping together and re-moralising the Conservatives through repeated misfortunes and disappointments over the best part of three decades, and then carrying the party to overwhelming electoral triumph in 1874, was largely a solitary and personal one.

There has been nothing like it in the history of British politics. It was a demonstration of courage and persistence of the highest order, especially coming from an outsider who had little in common – intellectually, emotionally, even spiritually – with the mass of his followers. Disraeli was able to rebuild Conservatism because he was, or became, a great leader. But he was not, like Pitt or Peel, a man of principle. He was a man of expediency. Indeed, he was an opportunist. Had opportunity offered, he would have been a Whig – or a Peelite. He became a Conservative, and remained one, because he could see no other way to power.

In Disraeli’s gradual ascent to office he coined a number of glorious epigrams about politics which can be, and have been, spatchcocked together into a body of philosophy. But the result is not convincing. Disraeli was capable of imparting political wisdom and some of his aperçus about men and events are memorable. But he had no world view. He did not really know how he would conduct himself in Downing Street until he got there. And when he arrived, what he did bore little relation to what he had said in Opposition. Throughout his political career there are profound contradictions. In office in 1852, he renounced protectionism, the principle on which he had overturned Peels’ great administration. In 1859, again in office, he introduced a parliamentary reform, the ‘Fancy Franchise Bill’, a measure of pure expediency for which he had no mandate and which bore no relation to anything to which he had previously committed himself. In 1867 he introduced and carried into law a Reform Bill which was more democratic and sweeping in character than ones he had previously opposed, and which Lord Derby, still his nominal chief, admitted was ‘a leap in the dark’. This had nothing in common with anything hitherto identified with Toryism under Pitt or Conservatism under Peel, and is inexplicable except in terms of a desire to stay in office by a spectacular coup.

Disraeli’s inconsistencies maybe defended on the grounds that he had no majority in the Commons and had to live from hand to mouth. But neither Pitt nor Peel would have accepted such an argument. Moreover, when Disraeli finally achieved not just office but power in 1874, and had a commanding majority in both Houses of Parliament, he took no steps at all to safeguard the agricultural interests on which his career as a party leader had been founded.

As a result, it was during his administration that the catastrophe of British farming as a result of cheap imports of grain – which he had predicted when he destroyed Peel in 1846 – actually took place. The Conservative nature of his Government, in so far as it had one, was achieved by ad hoc policies and political showmanship, such as the enthronement of Queen Victoria as Empress of India and the brokering of the Treaty of Berlin. There is no philosophical thread which runs through the 1874-80 Government, except the appetite for office and the determination to enjoy it.

Nonetheless, Disraeli’s phrase-making and showbiz skills, his search for power and his relish for it when it eventually came; the profound understanding, which he gradually acquired through hard experience, of how professional politicians use and manipulate social forces; and his analysis of the sophisticated nuts and bolts of politics at the highest level – all these characteristics have left an abiding impression on successive generations of Conservative politicians, especially the more imaginative ones. They love to quote Disraeli as an exemplar, especially to justify what they intend to do anyway. Though Disraeli was not in any meaningful sense a philosopher of Conservatism, it is impossible to imagine the modern Conservative Party without him.

There is, however, one respect in which Disraeli made a specific contribution to Conservative thinking. He was not the first One-Nation Tory. He never used the phrase. He certainly did not believe that it was possible, still less the mission of the Conservative Party, to turn the nation into a homogeneous economic whole, where class competition would cease to exist. This illusion is based on a passage in his novel Sybil, in which he deplored the deep division in the England of the 1840s, between what he called ‘the Rich and the Poor’ – a division which had ceased to exist in so terrifying a form by the time he achieved power in 1874. What he did discover was something quite different: that gaps between the classes, though profound, could be bridged by appeals to conservative emotions and needs in all of them, and hence that Conservatives, if they learnt how to make such appeals, had nothing to fear from democracy. This discovery may seem obvious – a truism, indeed – like all great innovations. But it was new at the time and it is of perennial importance to Conservatives. Democracy turned out to be the Conservatives’ secret weapon, and since Britain became a democracy the party has held power for more than three-quarters of the time. Disraeli was the first to perceive this truth, and make use of it; and it is this – and nothing else – which makes him a great Conservative strategist, perhaps the greatest of all.

As it happens, it was a young man from the next generation, Lord Randolph Churchill, who actually coined the name ‘Tory Democracy’, thus giving a label to what Disraeli had stumbled on as a fact. But Lord Randolph never built a philosophy on his phrase. He never got round to saying what it meant, which might have destroyed the magic. Asked to define it, he replied, in a moment of frankness and not for quotation: ‘Oh! Opportunism, mostly’. Less cool-headed than Disraeli, less analytical and profound, less a master of strategy, though often brilliant at tactics, he was nevertheless an operator in the Disraeli mould, in that he strove always to take political advantage of opportunities as they arose, without worrying too much about consistency. He rose by opportunism and fell by it, because his resignation as Chancellor of the Exchequer, in December 1886, was an opportunistic move which fatally misjudged the situation and involved no issue of principle at all. It thus brought about his political ruin, which illness made permanent. Like Disraeli, however, he lingers on in the imagination of young Conservative high-flyers as a brilliant political meteor, a pendant to the portrait of the great Beaconsfield.

The man who, by his masterly inactivity and patience destroyed Lord Randolph, the Marquess of Salisbury, added another dimension to Conservative philosophy – what can be called Enlightened Pessimism. This is worth examining in a little detail. Salisbury, unlike Pitt or Peel or Disraeli, could never have been at home outside the Conservative Party. He was born into it, and he thought himself into it even more deeply. He had much more in common with the Duke of Cambridge than he would have cared to admit. He thought all change likely to be bad, sooner or later. He was not born to the purple, however, and succeeded to high titles and vast estates by the accident of death. As a young man he was poor and earned his living partly by journalism, an activity he despised. He lacked the guilt-feelings of the eldest son, or the comforting optimism of those destined for great possessions that all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds. He viewed the future with profound apprehension. In 1882, not long after Gladstone had been swept back to power by a huge majority, Salisbury wrote: ‘It will be interesting to be the last of the Conservatives. I foresee that will be our fate’. He followed this, the next year, by a striking article in the Quarterly Review entitled ‘Disintegration’, in which he foresaw radical agitators taking advantage of every downturn in the trading cycle to wage ‘that long conflict between possession and non-possession which was the fatal disease of free communities in ancient time and which threatens so many nations of the present’. Salisbury implied that there was no ultimate way of eliminating this recurrent conflict, since disparities in wealth were inevitable and would probably grow. Nor was there any guarantee that the eventual outcome of the conflict would not be destructive of property, and thus of order and civilisation. In short, he took a gloomy view.

Salisbury’s empirical pessimism was underpinned by a philosophical pessimism based on his view of human nature. This attitude has been shared by a great many Conservatives, or conservatives, of all ages, and in a way is central to the political debate. Whereas radicals of all complexions and ages tend to stress the ideal of mankind, as a creature made in God’s image, and thus believe in his limitless improvement, indeed perfectibility – for them, Rousseau’s New Man is a distinct possibility – Conservatives see man as a flawed creature, a fallen being doomed to inhabit a vale of tears in this world. In the whole of the Bible, the teaching which seems most important to radicals is the Sermon on the Mount; to the Conservatives, it is Original Sin. Salisbury saw man as a wrong-headed creature to be kept under the close rein of natural and divine law, and under no circumstances to be permitted to devise, out of his own head, schemes for human improvement, which were sure to make matters worse. Some marginal changes for the better might indeed occur, where they evolved from well-tried existing institutions. Any major attempts at advance were best avoided or submitted to only under duress.

But if Salisbury saw the prospects ahead with apprehension, he never regarded them as hopeless. To him, Conservatism was an organised rearguard action – and the stress is on organised. He was the first Tory leader to pay detailed attention to organisation. He took aboard Disraeli’s and Lord Randolph’s point that working-men often possessed strong Conservative instincts which could be appealed to. Under his leadership, which spanned the 1880s and the 1890s, the modern Conservative political machine took shape. He held office as Prime Minister for 11 years in all, and no one since Walpole had used prime ministerial patronage with greater effect to build up loyalty to the party at all levels. He adopted Gladstone’s practice of addressing mass public meetings and encouraged his colleagues to do likewise. He believed the Conservative rearguard could stem the tide of anarchy for a time –possibly a long time, perhaps indefinitely – but would have to work hard to do it. He taught Conservatives to be politically efficient and to beat the big populist drum whenever possible. That is how he won the Khaki Election in 1900. Indeed, whereas Peel and Disraeli only won one election each, Salisbury won three; his example set the pattern for the twentieth century, in which Conservatives, or Conservative-dominated coalitions, have held office for 66 years, and Liberal or Labour a mere 30.

The twentieth century, then, has been largely a Conservative epoch. But the politicians who have led the Conservative Party during these 90-odd years have been, in strict party terms, a curious collection. It is quite impossible to construct a Conservative leadership archetype out of their personalities, views and records. Thus A. J. Balfour, Salisbury’s nephew and successor, was a defender of the aristocratic principle in Conservative Government, made flesh in his and his uncle’s eyes by the Cecil clan itself, to which both belonged. Their administrations, a virtual continuum, contained so many members of their family that they were known as the Hotel Cecil, after a splendid new London caravanserai opened in 1896. Yet the happiest period in Balfour’s life was when he was serving in the meritocratic coalition led by the plebeian adventurer Lloyd George. And in 1923, Balfour, consulted by King George V, was responsible for rejecting the claims to lead the nation and the party of Lord Curzon, who was a Conservative archetype. Balfour’s objection to Curzon, which may have been coloured by personal malice though the two had been friends all their lives, was remarkably un-Conservative: Curzon’s image, Balfour claimed, was too aristocratic, and he was in any event a member of the House of Lords. No Labour or Liberal had so far raised any fundamental objection to the Prime Minister sitting in the Lords, and it is in a way typical of the paradoxes of British Conservatism that the ban was initiated by one of its leaders, under no sort of pressure. Truly, Conservatives move in mysterious ways, their political wonders to perform.

Stanley Baldwin, the beneficiary of Balfour’s un-Conservative veto, did not fit into any obvious Conservative mould. The most remarkable act of Baldwin’s life was his gesture in giving a fifth of his wealth to the State. This was not merely un-Conservative but in a sense even anti-Conservative. On 24 June 1919 a pseudonymous letter appeared in The Times in which the author announced that he had calculated his wealth to be £580,000. Despite the huge increase in personal taxation which had taken place during the recent World War, and had been largely maintained since, the writer said he proposed to realise one-fifth of his wealth, buy War Loan with it and then cancel the certificates, thus, in effect, making a voluntary gift of £116,000 – worth about £10m today – to the State. He said he hoped that other members of the wealthy classes would follow his example to reduce the burden of war-debt. The letter was signed ‘FST”. Not even the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Austen Chamberlain, knew the

identity of the donor. Only years afterwards was it revealed that FST stood for Financial Secretary to the Treasury, his then subordinate Stanley Baldwin.

It seems astonishing that a man who, four years later, was to become Conservative leader should thus implicitly admit that the rich were under-taxed. Baldwin doubtless would have argued that his gesture was patriotic, and that in any case Conservatives were not necessarily the country’s low-tax party. There would have been some truth in such reasoning – another Tory paradox. Income tax, at 10%, was first introduced by a Tory Prime Minister, Pitt the Younger, in his May 1798 budget. It was abolished in 1816, in the teeth of resistance by Liverpool’s Tory Government, by a backbench revolt of radicals and Whigs led by the ultra-radical Henry Brougham who argued that income tax was inquisitorial, a huge invasion of privacy, a means of gratifying the State’s ‘passion for expense’ and ‘an engine that should not be left at the disposal of extravagant ministers’. He moved that not only should this hateful tax be abolished, but that all the paper-work connected with it be burnt so that it might never be reimposed.

All the same, income tax was reimposed, in May 1842, at seven pence in the pound again, by a Conservative Government under Sir Robert Peel, the man who founded the Conservative Party. It is a curious fact that the Conservatives not only invented and reimposed income tax, but have raised it as often as they have lowered it. It was another Conservative Chancellor, Neville Chamberlain, soon to be Conservative leader and Prime Minister, who in 1936 put up income tax to what he called a ‘more convenient figure’. ‘Convenient’ is an odd word for a Conservative to use about a personal tax increase. But then, Chamberlain himself was an odd Conservative: the son of a radical and Liberal Unionist, who himself made his name in gas-and-water politics in Birmingham and then, in government, became a notable social engineer and high-spender. High spending has often been a twentieth century Conservative characteristic. When the Earl of Home renounced his title in 1963, in order to become Prime Minister and party leader, and stood for the Commons at a by-election in Kinross and West Perthshire, his inaugural meeting was remarkable for the lavish spending plans he unrolled. Home was an old-fashioned grandee landowner, in his private capacity a man with a reputation for parsimony. But wearing his prime ministerial and party hat, he was – almost – the last of the big spenders.

It is hard to find any twentieth-century Tory leader who fits into a conventional Conservative-archetype slot. Bonar Law and Winston Churchill, for example, were not so much Conservatives as imperialists. Law came into politics almost entirely because of his admiration for Joe Chamberlain, radical-Liberal Unionist, whose notion of empire, as Law put it, was ‘the very essence of my political faith’. It was Law’s devotion to the Union, and in particular to the Union with Ireland – he saw it as the keystone of the entire imperialist arch which, once removed, would jeopardise the whole – that effectively made him Conservative leader in 1911, when the Ulster crisis loomed. Churchill, too, was first to last an imperialist who, in domestic terms, was a reformer; almost a radical one. He hated the label ‘Tory’ and put up with ‘Conservative’ only when he had to. He left the Tories in 1904 and, as a Liberal minister for 10 years, he worked hard with Lloyd George to lay the foundations of the British welfare state. He rejoined the Conservatives in 1923 because it was the only way he could pursue a political career. Between 1929 and 1939 he was at odds with the leadership and most of the party, and when he became Prime Minister of the coalition in 1940, thanks mainly to Labour support, it was clear that the Conservative rank and file in the Commons preferred Neville Chamberlain to him. By the time the war was won, Churchill and his supporters controlled the party and he remained the most valuable Tory asset. But he was never at ease as Conservative leader. Bill Mallalieu, for many years the MP for Huddersfield, told me that, when Churchill was very old, he once shared a Commons lift with him. Churchill focused on him and asked: ‘Who are you?’ Bill told him. ‘Labour?’ asked Churchill. ‘Yes.’ Churchill paused, then said: ‘I’m a Liberal. Always have been‘.

Of the remaining Conservative leaders in the twentieth century, all – with one exception – were men of the centre. Baldwin was an eirenicist, happiest when enjoying all-party support, as during the abdication crisis in 1936, or when serving as major-domo under the nominal leadership of the National Labour Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald. Anthony Eden came closest to being a pure Conservative and even associated himself with a variation of the old Tory Democracy: he called it ‘a property-owning democracy’. But he never did anything to make good this slogan during the 20 months he was in office. Harold Macmillan, who sat for what was essentially a working-class seat in the North East during the 1930s (he lost it in 1945 and then shifted to a Conservative Home Counties’ stronghold), set himself up as a mixed-economy corporatist with his book The Middle Way, published in 1935. He retained some, if not most, of these ideas to the end of his life. It seems perverse that during Margaret Thatcher’s prime ministership he condemned the privatisation policy, which transferred assets from the State, where they were mismanaged by bureaucrats, to the private sector, where they were successfully run by professional businessmen and owned by millions of ordinary people, as ‘selling the family silver’ – a phrase associated with impending bankruptcy. Macmillan, despite – or perhaps because of – his grandee postures, had little in common with most people who voted or sat as Tories in his lifetime. He was closer to being a Whig; indeed, he once told me, at the Beefsteak Club, that he was a Whig. His two favourite characters were the old Marquess of Landowne and the Duke of Devonshire, Macmillan’s own father-in-law, who, according to him – and he related this with delight – ‘never set foot in the Carlton Club in their lives’, preferring Brooks’s. Edward Heath and John Major, in their different ways, were – or are – suburban versions of Macmillan’s ‘middle way’.

The one exception to this trend of leadership was Margaret Thatcher. She was not merely a Conservative radical who repudiated many of the assumptions accepted by Conservatives in the Peel tradition: she can be called a genuine reactionary. She accepted the notion, first put forward by her mentor Sir Keith Joseph, that post-war Labour governments, and the changes they had introduced, operated a ‘ratchet effect’. No move they made to the Left was ever reversed by subsequent Conservative administrations; each merely served as a prelude to the next cog in the ratchet. Joseph speculated about the possibility of reversing the ratchet effect in a right-wing direction, but it was Margaret Thatcher who actually put this policy into operation, not across the whole board of politics – she left the welfare state alone on the whole – but over trade unions and the public sector. She thus decisively repudiated the Peelite maxim that it was the task of Conservative administrations to accept, build on, and operate efficiently the reforms of their opponents. This is something not even Salisbury dared to carry out. It marks the most important change in the character of Conservatism since the party was first christened by Peel in 1834. Indeed, it is so important that its full implications have yet to be worked out. What can be said, however, is that it has already changed the agenda of British politics, which to some extent is now concerned with examining the reforms of previous generations and, if necessary, reversing them. The Labour Party, under the leadership of Tony Blair, has also adopted this policy and it could be that it will be Labour which will abolish the welfare state as it now exists, by undermining its universality. In 1894, Sir William Harcourt, illustrating the working of the ratchet effect in the nineteenth century, exclaimed: ‘We are all Socialists now!’ Today, at the close of the twentieth century, it would be closer to the truth to say: ‘We are all reactionaries now!’

Enough has been written about the practice of Conservative leadership to suggest that it is not shaped primarily by ideas, and certainly not by any one stream of ideas. It is more a matter of attitudes and personal predilections – even quirks – and responses to contemporary forces and happenings. I was once present when a journalist asked Harold Macmillan what was the biggest single factor in shaping his policies as Prime Minister. ‘Events, dear boy; events!’ said Macmillan, cheerfully. Peel would have agreed with this view. He once remarked that England would have been a better place, and a happier place, and most certainly a more Conservative place, if the industrial revolution had not occurred.

Thus the Conservative Party is driven by events, and the need to accommodate them, rather than by ideology. Tory and Conservative leaders have, of course, received instruction from the leading minds of the day. In the 1780s Pitt the Younger had Professor Adam Smith to 10 Downing Street and listened carefully to what he had to say. Peel corresponded with a number of intellectuals and ‘experts’ such as Bentham and Mill, and had a close and instructive friendship with the Anglo-Irish Tory guru, John Wilson Croker – albeit it ended in estrangement when Peel repealed the Corn Laws. Disraeli and Salisbury both read widely, though it is doubtful whether either was guided by any particular thinker; and Balfour, though an intellectual himself, ring-fenced his philosophical enquiries from the practical business of politics. Lord Longford told me that when, as a young Tory, he had a walk with Stanley Baldwin at Hatfield in 1936, he asked the Prime Minister who had influenced him most. Baldwin was at a loss how to answer the question, stopped in his tracks and thought hard. Finally, he dredged up from the dim recesses of his undergraduate experiences the name of Sir Henry Maine. ‘Maine taught me’, he said, ‘that the most important progression in human history was the change from status to contract’. Then he paused again and a mischievous grin spread over his knobbly features. ‘Or was it the other way round?’ There spoke the true Conservative.

In a letter written by the Earl of Derby to Disraeli in 1875, there is a telling aside. ‘The Conservatives’, he remarked, ‘are weakest among the intellectual classes; as is natural’. Here again, Margaret Thatcher, as leader, might appear to be an exception. She made great play with the influence on her of Hayek and Karl Popper. She had undoubtedly read their books and absorbed them and often quoted from them. But whenever I cross-questioned her about her core beliefs, I came to the conclusion that nearly all of them were derived from the obiter dicta of her father, a grocer and Conservative local councillor. Most Conservatives – Pitt, Peel, Disraeli, Law, Macmillan, as well as Thatcher, are outstanding examples – learn more from their parents and grandparents than from anyone else.

The answer, then, to the question: What is a Conservative? is that a Conservative is made by heritage, circumstances and the society in which he or she lives. There can be all kinds of Conservatives; always have been; always will be. There is no archetype; no workable definition.

In a way, Conservatives find the same problem in defining themselves as the founding fathers of Israel when they tried to define a Jew. In the end they decided that anyone was a Jew who thought himself, and called himself, a Jew. Recently I sat at lunch next to a lady who had been married all her adult life to a Conservative peer. She told me that there were three things she would never change under any circumstances: her nationality, her religion and her Conservative allegiance. I asked her to define ‘Conservative’. She replied: ‘That is a question no true Conservative should ever be expected to answer’.

There are some people who are born, or who come to feel themselves, Conservatives. The existence of this large number of people, from generation to generation, is the fundamental strength of the party and the reason it will probably continue to be the party which rules Britain most of the time. That, of course, will not save it from periodic setbacks, sometimes on an enormous scale.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.