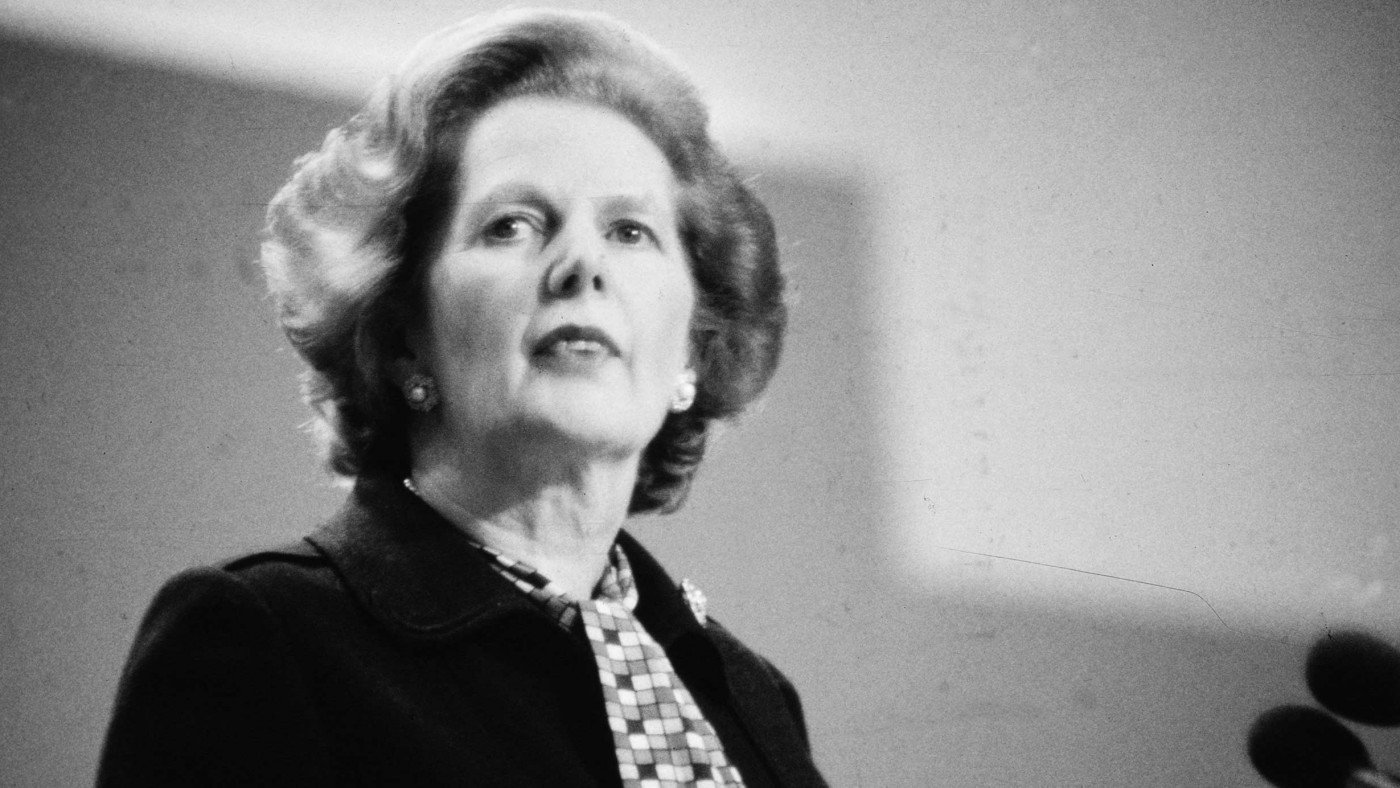

This week, I was invited to speak at the Cambridge Union in support of the motion ‘This House believes Britain needs a new Thatcher’, below is an abridged transcript of my remarks.

Every Conservative – from the grizzled Rotarian to the rubicund undergraduate – yearns for a return of Margaret Thatcher. Not just out of perverse nostalgia, but out of a longing to rediscover the clarity and purpose she gave to the Conservative cause, and which won the party three successive elections.

That yearning perhaps explains why they chose Liz Truss as their leader. Indeed it could be said that her premiership is a standing rebuke to the idea that Britain needs a new Thatcher – we tried it and it was a disaster. But for me the Truss experience demonstrates that there was far more to the Thatcher project than a caricature. If all she had ever done was talk tough and cut taxes, she would never have won elections or changed the country in the way she did.

So in arguing that Britain needs a new Thatcher, I’m not going to suggest that we need to go back to the 80s – we are facing a completely different set of challenges. But there are three ways in which the historical circumstances are similar, and where we could learn from her example.

We have an economy gripped by high inflation. We are living in a dangerous and uncertain world where democracies face enemies ideologically opposed to our way of life. And we are at a political turning point where the status quo is no longer viable, and we need a leader with an iron-clad determination to change course.

On inflation, you don’t have to be Milton Friedman to recognise that money printing might be a factor. But it has suited both the government and the Bank of England to blame factors outside their control, rather than acknowledge the role that injecting £1trn into the economy via quantitative easing since 2008 has played. Thatcher would never have pretended this wasn’t a political choice.

It was a Soviet propagandist who gave her the sobriquet ‘Iron Lady’, of which she was immensely proud. It stuck, not just because it was so evocative of the Cold War era, but because of her strength on the world stage – a strength which came not just from her relentless defence of British interests, but also from her moral purpose.

It’s scarcely imaginable that a politician today could tell a journalist, as she did, that she was ‘in politics because of the conflict between good and evil and out of the conviction that in the end good will triumph’. Her free market ideology was underpinned by her Christian faith – and those two hand-in-hand determined all her decisions. For voters, that meant if you could recognise her intellectual framework, you would know how she would respond in an unforeseen situation.

Russia, China and Iran represent an enemy blurrier in its outlines, more diffuse in its aims, but no less hostile to democracy than the Soviet Union or the Argentine Junta. Whatever happens in the next few years, the British people deserve to know the basis on which decisions will be made in their name.

Finally, it is fashionable to dismiss the great man – or woman – theory of history and to downplay the significance of Thatcher herself as an individual. But her government did represent a significant break from the post-war consensus. And this wasn’t just a political project but an intellectual one.

A key objection to revisiting this approach to politics is that it was divisive, but Britain is already divided – not just between north and south or Brexit and Remain, but between young and old.

Spending on the over-65s is projected to increase by 11% of GDP by the 2070s, amounting to over £250bn per year. Debt will rise to 267% of GDP in 50 years if spending on health, pensions and social care continues at its current trajectory. Young people will spend their working lives paying ever more tax to pay for the pensions and healthcare of older generations who never had to make those same sacrifices.

These are not the results of active policy decisions but of sleepwalking onto a completely unsustainable path. We need to change course, and we need a leader who is prepared to take on vested interests and win a battle of ideas.

My instinct may be that these qualities are most likely to be found in a leader from the right, but it does not necessarily have to be so. Both sides of the spectrum would benefit from having politicians with a clear framework of ideas and the ability to articulate them, who had the courage to respond to events out of conviction rather than expediency and who refused to countenance British decline.

Marxist Historian Raphael Samuel wrote of Thatcher in 1992, ‘she stumbled on issue after issue of high principle, where there were genuinely incompatible moral choices to be made’ thereby forcing the left into defining its own position. ‘I for one regret that there is no longer anyone to keep us on our ideological toes’.

Left or right, Britain needs a new Thatcher.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.