This is the weekly newsletter from Iain Martin, editor of CapX. To receive it by email every Friday, along with a short daily email of our top five stories, please subscribe here.

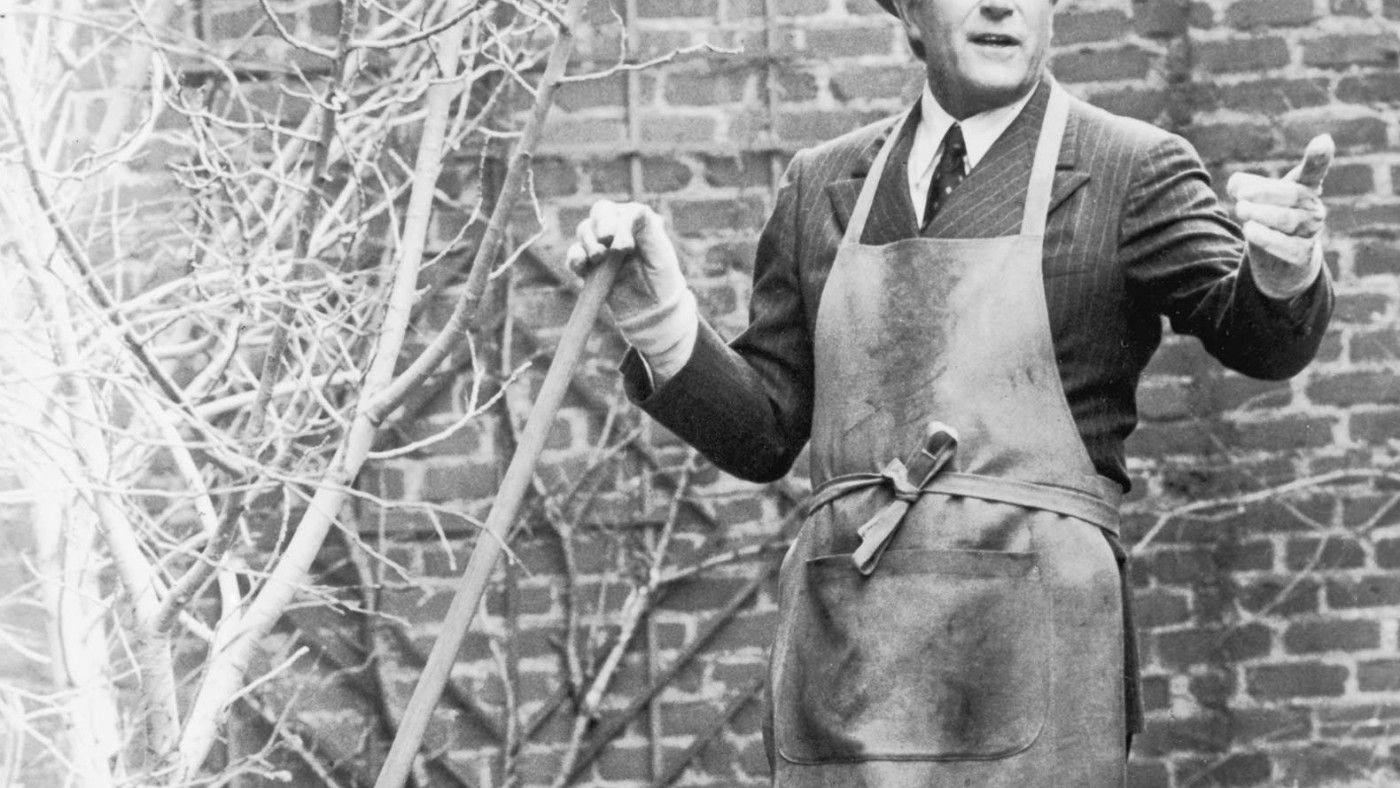

In Being There, Peter Sellers’ last great piece of work, he plays a gardener who by virtue of a case of mistaken identity ends up being hailed as a deep thinker and potential leader of the United States. Following the death of his wealthy employer, the humble Chance stumbles into the path of American plutocrats who mishear his name as Chauncey Gardiner. His mundane observations about gardening are taken to be profound insights on economics and the condition of the nation. Celebrity status ensues. Don’t worry, if you haven’t seen it I won’t spoil the ending, but the extraordinary rise of Jeremy Corbyn, the accidental new leader of the left of centre British Labour party, did remind me of Sellers and the plot of Being There.

This week, it was Labour that completely lost the plot. The hard left Corbyn – like Chance a seemingly simple-minded fellow invested by others with qualities he does not possess – followed up his landslide win in the party’s leadership contest by standing silent at a service in St Paul’s Cathedral to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Britain. This was unfortunate, to say the least, as he was silent during the singing of the national anthem. It is not even clear that Corbyn, a committed republican, knows the words of God Save the Queen.

This blunder came in the middle of days of chaos, of strange statements, multiple policy three point turns and botched appointments, the worst of which was the choice of John McDonnell as Shadow Chancellor. The hard line socialist McDonnell, who is almost unknown outside Westminster, was introduced to the British public with a row about comments he had made in 2003 that were supportive of the IRA, the terrorist organisation that murdered more than 1800 civilians and members of the security services, bombed its way across England and tried to kill Margaret Thatcher. Several years ago, McDonnell himself “joked” about assassinating the former Prime Minister. He also apologised for that this week, sounding a little more convincing than when he delivered a tortuous explanation of why he had hailed the “bravery” of the IRA.

For moderate Labour types, and for the few remaining dedicated supporters of the former Labour leader Tony Blair, winner of three UK general elections, this is, of course, painful to watch. Corbyn and McDonnell are producing the political equivalent of a horror movie in which their party is trapped, stuck in the basement, with little hope of rescue. The MPs need to do in Corbyn but cannot because there is no mechanism in place. Even if they try, the membership would be furious and put up another old-school leftie in the subsequent leadership race.

Meanwhile, Corbyn’s early poll numbers and trust ratings are poor in the period when a new leader should expect a honeymoon.

It all serves as a reassuring reminder that despite the talk in recent years (from people like me) of the old model of politics being broken, with disaffected voters shunning spin in search of supposed authenticity, there are still basic levels of competence expected. A leader who aspires to run the country should be able to make speeches (Corbyn can’t), assemble a team, sing the national anthem of the country he wants to run and avoid association with people who have to apologise for their views on terrorist groups. Of course, Corbyn and McDonnell are close friends and have similar views on the IRA’s “armed struggle.”

And when it came to it in May, sufficient British voters pragmatically rejected the economic risk of Labour under Ed Miliband and a majority government resulted. David Cameron’s style – calm and largely undemonstrative – had significant appeal, but he is committed to leaving in this parliament.

Yet, the emergence since then of Corbyn is not an isolated phenomenon. Populist, extreme leaders have risen to prominence in Spain, Greece and France and beyond. Mainstream Nationalists in Scotland have all but wiped-out the Scottish Labour party, while the UK”s Eurosceptic Ukippers secured almost four million votes at the general election in May.

In politics, the plates seem to be spinning ever faster as the world changes rapidly. This week in Australia, the Liberal Party removed its latest leader, Tony Abbott. That party seems now to be driven almost exclusively by opinion polling, to the extent that a healthy fear of the electorate’s displeasure has turned into a mania for sudden coups.

And then there is Donald Trump, the property tycoon and cartoonish carnival ringmaster who commands the stage in the Republican race in the US.

What all of these developments have in common is that the devotees of these leaders are absolutist. Many of the disciples are extremely angry and wildly intolerant of the views of opponents they regard as sworn enemies or traitors. This seems to owe a lot to the power of the internet and the opportunities it creates for the development of closed communities. Post-industrial atomisation is not the problem as was once feared. Instead, like-minded individuals can cluster together online, angrily amplifying each other’s views, bypassing the mainstream media and dismissing awkward facts as smears from opponents.

In the US, this presents a tremendous opportunity for a leader (a Reagan would do nicely) who might address directly how destructive and small-minded politics is becoming and endeavour to focus on the exciting economic possibilities and tell a story that unifies those who disagree on other subjects. But where is he or she?

Incidentally, the other comic classic worth mentioning in the context of Corbyn is Monty Python’s Life of Brian. At one point, Brian loses patience with the throng who have wrongly decided that he is their saviour. His mother tells the adoring crowd: “He’s not the Messiah. He’s a very naughty boy. Now go away!”

Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn is part Chauncey Gardiner and part Brian, a blank screen onto which his followers and disciples are projecting their hard left fantasies. They won’t like the ending.