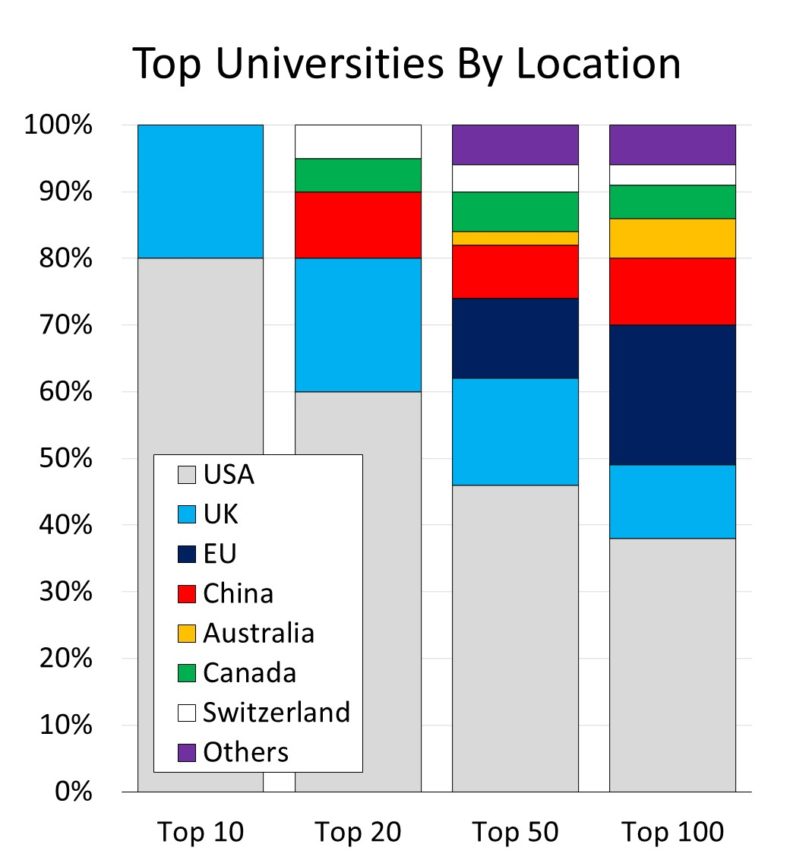

As commentators continue to dissect the Chancellor’s budget performance and the impending age of the trillion-pound state, it’s worth turning to one compelling statistic from his speech that seems to have slipped under the radar: ‘With less than 1% of the world’s population, we have four of the world’s top 20 universities’. Sunak was definitely on to something with this point, as the graph below indicates.

In higher education, the UK outperforms its apparent potential by an order of magnitude. Despite accounting for less than 1% of the world’s population and only 3% of global GDP, we have 11% of the top 100 universities in the world, including the only two non-US institutions in the top 10 – Oxford and Cambridge – and more universities in the top 50 than the whole of the EU combined. In fact, the only country that does better is the USA, which accounts for 24% of world GDP. Nowhere else even comes close – yet.

This analysis is based on the latest data from the Times Higher Education World University Rankings. Obviously it’s important to be aware of the underlying methodology of this prestigious league table, but on the whole, it seems pretty robust. Importantly, unlike other university league tables, it does not make use of direct measures of student satisfaction, which can be distorting. Volatility year-on-year is also pretty limited.

So in terms of quality university teaching, research output and research influence, the UK really does do very well. And this holds true however you slice the data, whether by grouping the STEM or the arts subjects together, for example, or by looking at individual subjects.

Indeed, in some disciplines the UK’s relative prowess is even more pronounced. For instance, Britain accounts for four of the top 10 universities in the world for clinical subjects, while London alone hosts four of the top 100: Imperial, UCL, KCL and QMUL. The capital outperforms entire G20 nations in this respect – Japan and South Korea each only account for two of the top 100 universities for clinical studies, for example.

Recognition of the UK’s comparative advantage in higher education has long underpinned universities policy. Tony Blair’s invocation of the ‘knowledge economy’ is probably the most memorable expression of this, but the basic idea still informs thinking today. As set out in its R&D Roadmap and Integrated Review, the Government aims to make the UK a ‘science and technology superpower’. Partly this is about levelling up the country and creating a high-wage, high-productivity economy, and partly it’s about enhancing Global Britain’s geopolitical heft.

And of course, Britain’s universities are fundamental to this vision – the research base upon which the technological superstructure can be built.

However, the Government would be unwise to take the strength of these foundations for granted. External and internal threats are chipping away at some of Britain’s great educational institutions.

The obvious external threat is China, which has been pouring money into top institutions such as Peking and Tsinghua. In the long run, Britain is not going to be able to compete with Beijing’s raw spending power. On the other hand, the atmosphere in China is not conducive to academic freedom of inquiry, and four of the top 10 Chinese universities are in Hong Kong; it remains to be seen how these institutions will fare now that many of the city’s best and brightest are emigrating to escape the clutches of the CCP.

The more insidious threat comes from Chinese money subverting freedom of expression here in Britain, as exemplified by the ongoing saga at Jesus College, Cambridge. Still, commentators and policymakers are more alert now, so perhaps this threat shouldn’t be overplayed.

No, the biggest problems are home-grown and more intractable: a set of deeply rooted structural and cultural issues that need addressing if Britain is to remain a ‘world-leader’ (to use Sunak’s phrase) on this front.

First, an over-emphasis on published papers has resulted in academia increasingly prioritising quantity over quality. Too much time gets sunk into applying for funding, rather than pottering around in the lab or library. And job insecurity drives many talented early careers researchers out of the sector. Basically, incentives are misaligned and the system has become a bit broken.

Incentives are out of whack when it comes to funding too. Universities do not bear the costs of badly educated students failing to repay their student loans, so can afford to expand by offering poor quality but cheap-to-run courses at full whack. Many students thus end up doing bad courses at subpar universities.

That feeds into a broader issue, that the last few decades has been marked by a philistine tendency to see universities mainly as engines of social progress or economic growth. This inevitably detracts from their raison d’etre: knowledge. But when we treat education as an instrumental rather than an intrinsic good, standards decline and they end up being neither one thing nor the other.

Last but by no means least, the excesses of Wokery are having a chilling effect, prompting self-censorship and driving out good academics. The hounding of academic Kathleen Stock at the University of Sussex is just the latest in a series of alarming incidents.

So the Government has got its work cut out, if the ‘science and technology superpower’ ambition is to be realised. More money for R&D is welcome (even if the Chancellor has pushed back the timeline by a couple of years), especially if it can crowd in private investment. But structural and cultural reforms are needed too, if Britain’s universities are to remain top centres of research and innovation.

Intangibles such as inventiveness, insight and academic excellence can be pretty hard to measure, so here’s a benchmark for the Government: in a decade’s time Britain – with less than 0.8% of the world’s population – should account for at least 20% of the world’s top 50 universities. Now that would be something worth tuning into the budget to hear.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.