Boris Johnson and the Conservatives’ connections to provincial England remain intact. These were shown to impressive effect in the Brexit referendum and 2019 election, and the latest round of election results confirm it. The Tories won seats across England from Harlow to Durham, failing to gain ground only in uber-Remain areas and the core of large cities with lots of younger graduates and ethnic minority voters.

The delivery of Brexit and the successful vaccine rollout – and the fact that we did not have to waste time on the EU’s disastrous attempt to co-ordinate vaccines – have cut through. This has bought time; now it has to be effectively used.

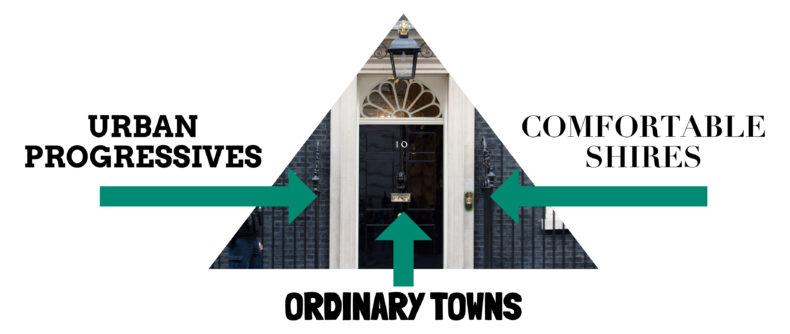

The new groups of English politics – and Morton’s electoral triangle

English politics consists of three major blocs. The first are the urban progressives, centred in London, the large cities, and the university towns. Cosmopolitan and virtue signalling, over-represented in the bureaucracies of large corporates, professions and government, shielded from market pressure and determined to lecture, tax, nudge and bully everyone else.

The second are the comfortable shires, older and home-owning, with lots of small businesses but fewer graduates, patriotic and in favour of good core public services (think police, pensions, schools, hospitals).

The third are the ordinary towns – mostly in the Midlands and North but also the less affluent parts of the South from Cornwall to East Anglia. Poorer than the comfortable shires, but sharing many values, focused on good core public services while additionally worrying about their social fabric, this is the group that has swung most heavily to the Conservatives in recent years.

Of course, all three of these descriptions contain something of the caricature. But it is true that if you know someone’s view on, say, the car-based economy and immigration you can probably guess their views on identity politics, net zero, or more or less regulation for small businesses.

Politicians do not have enough time and money to try to satisfy all three of these blocs, and any electoral coalition has to span two of these blocs in order to win sizeable majorities. So the key to a successful political project is to cement your support among two of those groups even if it means annoying the third – what I call Morton’s triangle, shown below. The raw facts of time, effort and money preclude satisfying all three.

.

The politics of the new (winning) Conservative party are already set

The Cameron project tried to fuse urban progressives with the comfortable shires. It certainly improved on the party’s lamentable performance since 1997. But it failed to win a majority in 2010 and only won a small majority in 2015 when left-wing voters refused to vote Liberal Democrat, ironically in reaction to the Coalition. Cameron did achieve various worthwhile things (school reform, deficit reduction, universal credit, tax reforms, same sex marriage, an EU referendum) but politically, Cameronism was not as electorally potent as Johnsonism, even before it was killed off by the Brexit vote.

By contrast, Vote Leave in 2016 and then the Conservative Party in 2019 (at least in England) overwhelmingly and successfully fused the comfortable shires and the ordinary towns. The promises to get Brexit done, avoid tax rises while not continuing ‘austerity’, and improve key public services while levelling up all came together to give the Tories their first substantial majority and highest share of the vote since the days of Thatcher, one that would have been even bigger without the Brexit Party. This means the Tories can go into the next election with a default expectation of a Thatcher-style majority – and in England itself an absolutely crushing majority of over 150. This is the winning reality for the Conservative party of the 2020s – regardless of the fact some in Westminster don’t like it – and it is not going away.

The biggest threat to Boris Johnson and the Conservatives is … Boris Johnson and the Tory 3%

So who or what can reverse this new majority, or bring Boris – the Tories’ biggest electoral asset in decades – down? Not Sir Keir Starmer, who goes from tragedy to farce. The biggest threat to Boris Johnson is Boris Johnson himself, a man who loves to have his cake and eat it. And that’s because trying to please all three groups of the electoral triangle will lead to indecision and failure.

The problem for the Conservatives might be best described as ‘the Tory 3%’. These are the 3% of Tories who opposed the recent cut in international aid – a rounding error. This group however are heavily over-represented in the top echelons of the party hierarchy. These Conservatives long to be loved by the urban progressives they live among, even if it means letting down the other 97% of their voters.

For the comfortable shires and ordinary towns actually agree on a lot. For example, they are mildly worried about the environment, but just 6% of 2019 Conservative voters say they are prepared to pay more (by which they mean literally anything more) on domestic heating/electricity to decarbonise, or 28% on fuel, 18% on meat and dairy, and 22% to pay more in taxes in general. The idea of asking people to pay the eye-watering sums green campaigners want is clearly a fantasy of epic proportions. Of course, supporting hydrogen and nuclear might help reduce emissions without huge increases in bills, but there is a real issue that the cost of net zero could well be unacceptable to many of the party’s voters.

Another example of the triangle is on social care. The rumoured plan for a cap on costs will go down like a cup of cold sick among Blue Wall MPs, at least without heavy modification to the original Dilnot proposals. One astute Blue Wall MP described the idea of all home owners paying the first £50,000 of any care costs to me as “the social care poll tax”. But making the richest pay more instead will go down like a lead balloon in the comfortable shires. The obvious solution (as proposed by the Centre for Policy Studies and Damian Green MP) is for a version of social care that gives everyone a basic level but allows top-ups. And if you follow the logic of Morton’s Triangle, it’s progressive causes that should be squeezed to pay for it – starting by the vast subsidy of around £12 billion a year we give to poor quality universities (or take a look at the £30 billion in savings listed here).

The members of the new provincial alliance might not understand the detail of government reform or read the meandering thoughts of Westminster wonks, but they feel there is a great deal of waste in the system, as James Frayne, one of the few pollsters to understand this group, keeps warning. And if taxes go up while services don’t radically improve, they will reject the Conservatives.

Likewise, there is no point in a ‘war on woke’ if people begin to feel that you are just striking an empty pose. The new Tory voters might not follow politics but they have a keen sense of the value of money and that talk (particularly on standing up for our shared culture and heritage) is cheap, while paying for things and steadily fighting back the woke onslaught is costly and fiddly.

But ultimately, if Boris Johnson cannot accept the fact that he has lost urban progressives – and not just lost them, but is despised by many of them for his role in delivering Brexit – then by spending precious time and money on these voters, he will let the winning Tory coalition of shires and towns slip through his fingers.

Boris Johnson and the Tories must deliver for their provincial alliance to retain power

What unites the provincial alliance is both a dislike of the condescension of urban progressives and a sense of patriotic fairness.

This group do not want big government – they want fair government. They don’t want to bash the rich or corporations, they just want them to pay their share (which most already do). They don’t want a big welfare state, they just want those who have contributed to not always go to the back of the queue. They don’t want a Britain that loves expensive virtue-signalling on the world stage at the cost of core public services or higher taxes at home. They believe in individuals taking responsibility for themselves, and they see that as a moral issue – and believe the Government should too.

Similarly, they are not intolerant, nor in any real sense are most of them social conservatives (indeed, Boris’s chaotic private life probably reassures many he is not trying to roll society back to the 1950s). But they are sick of being told their country is uniquely bad, full of uniquely terrible people (particularly white people or men), and want a leader who is patriotic and fights back against the intolerant, nannying urban progressives. Forcing others to live and let live might be their motto – and they will not be bought off with the occasional tutting from No10.

This then is the real lesson of last Thursday’s election. Boris and the Conservatives will only lose if provincial England feels that it is being neglected, so that the Tories can flirt with a group of urban professionals that despise both ordinary provincial England and the Conservative Party. It is against this iron triangle of voters that every decision must be held up if the Conservatives want to be assured of victory in both the next election and potentially more to come after that.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.