Ben Thomson, an Edinburgh businessman with a small think tank, Reform Scotland, has unveiled a new plan for more radical devolution of powers to Scotland. It proposes that the bulk of financial and economic issues be devolved – budget, tax, borrowing – and only monetary policy, defence and foreign affairs would be reserved to Westminster.

Scotland would stay on the pound, continue to trade freely within the UK, with unimpeded movement of people and capital. The Scots – with the English, Northern Irish and Welsh – would remain British.

The Barnett formula – which presently produces an annual subsidy to Scotland from the UK Treasury of £10-12bn – would go, though a ‘social fund’ would remain. Thomson has said that, to bring down with a present budget deficit of 8-9 per cent, a fully devolved Scotland would have to raise taxes, or spend less (or both) – “if you want to stand on your own two feet, that is the price you have to pay”.

It’s a relief to have that said clearly. The SNP’s present economic plan for Scotland after secession – the 2018 report of the Sustainable Growth Commission – does shyly admit a period of mild austerity might have to be in force for some years after independence. But Scottish National Party leaders never refer to it, and the accent is on a presumption of strong growth thereafter, with Scotland reaching the level of the Scandinavian economies relatively quickly.

Ben Thomson’s plan wouldn’t satisfy core nationalists because it would keep Scotland in a UK outside of the EU, would veto the closure of the nuclear-carrying submarines’ base at Faslane and would not allow any separate diplomatic network, or a change in foreign policy orientation. It would, however, reduce the reasonable English grumble that a subsidy was going to a region which is one of the richer parts of the UK – rather than to poorer English regions. It allows Scots to make a realistic assessment of the strength of their economy. It could avoid the bitter division independence would usher in. It would be a radical departure from Treasury control: and might wean soft nationalists away from the independence option.

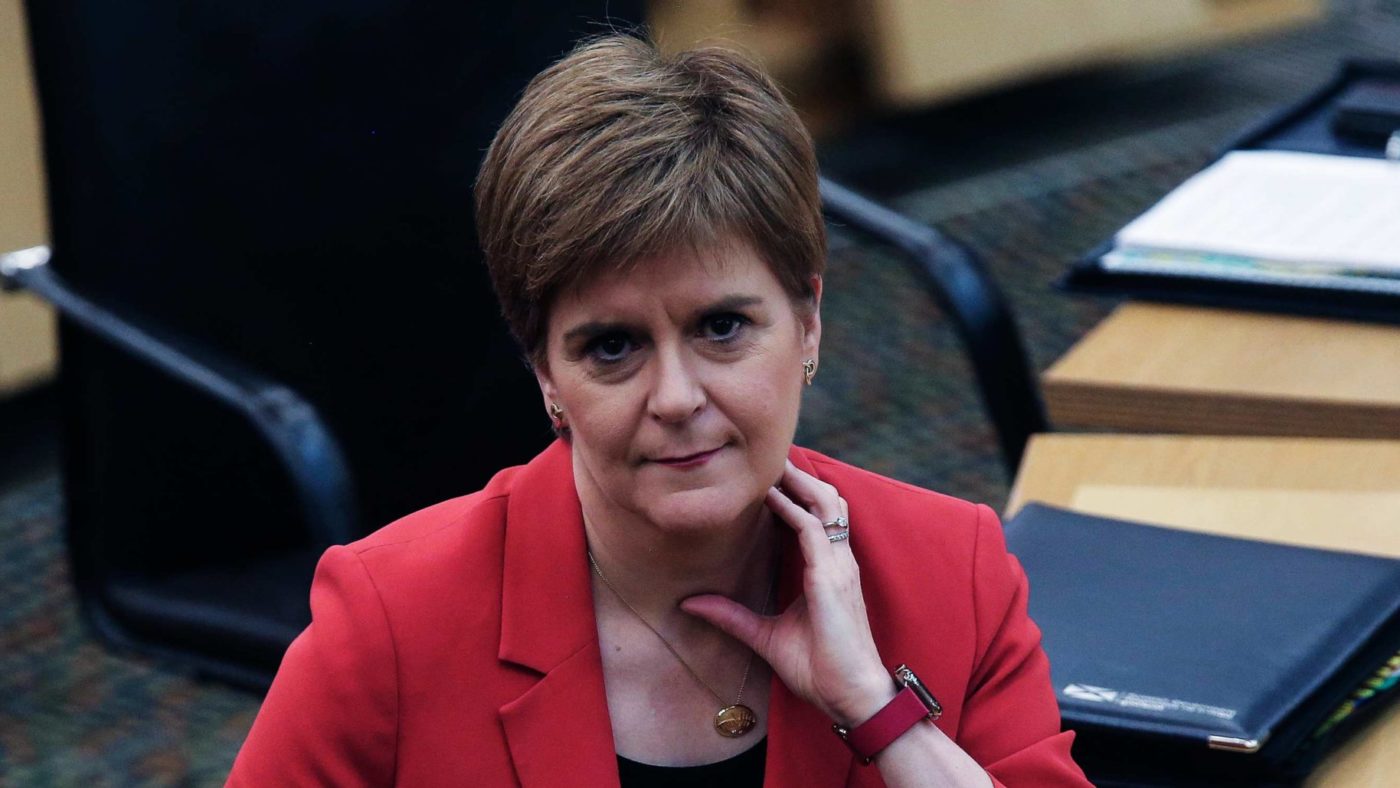

Yet it could also weaken the union further. The former SNP leader and First Minister, Alex Salmond, once considered this plan – known as the Devo Max option – as an alternative, probably because he judged that it would be a step nearer to secession. Each move taken in that direction in the past has strengthened the SNP’s hand. Though he and present First Minister Nicola Sturgeon are now enemies, both came into politics to achieve full statehood for Scotland. For them, Devo Max would be a pause, not a destination. Given an improved UK – and Scots – economy, the SNP would call on the Scots to make one more heave, a less strenuous heave than before – and Freedom! could be theirs.

For now, the battle favours the nationalists because their aim is clear; the ‘English’ government, especially the Prime Minister, is easily caricatured as a bunch of upper class bumblers and the European Union – of which the SNP has a rosier view than any of the states which are members – is denied to them, despite Scots having heavily voted for continued membership in 2016.

For all its evasiveness and unmoored economic assurances about an independent future, the SNP’s standard is one behind which men and women can stand. It seems to enshrine an ideal, promise of a fuller civic life, a pledge – in a nation once famously pious, now largely shorn of faith – of a more meaningful existence. Every successful nationalist movement must combine the talents of the con man and the revivalist preacher.

Unionism cannot match that with a strategy of reluctant adjustments to the status quo. Until now, British governments have appeared largely insouciant over the Union’s continued existence, anxious, it seems, not to show enthusiasm, let alone passion, for fear of giving offence.

There is a Unionist vision. Its most obvious advantage is that it is a fiscal union: the taxes of the southern English assist the largely ungrateful Celtic nations to support a higher standard of living than they could support if independent. That realisation won the 55-45 vote for the Union in the 2014 referendum on independence: it will continue to be important in any future such test. It has been and remains a very large achievement: it is now far from enough.

The vision will depend on the UK making a success of its post-EU place in the world economy: however we voted, remain or leave, that’s where the maintenance of our standard of living will be tested. If we can make a good fist of this, the Union can be secured – though it will take more than that.

It must work out a way of devolving powers – city regions presently seem the most promising route – which will be an alternative to federalisation in an England that does not wish to federalise.

It must ensure the closest possible relations – never mind the bruises – with the countries of Europe, and with the European Union itself. It must develop smart government-company relationships to manage the coming digital upheaval with the adoption, everywhere, of artificial intelligence: a project which is likely to require a new sort of labour market.

It must draw on and showcase the traditions and cultures of all the nations and regions of a Britain which has long been diverse and is now much more – and for the most part, cheerfully – so. It must make education at every level both a more serious endeavour than it often is, and a more creative one. It must, as a medium-sized state with as large a global network as any, play a significant role in coping with poverty, conflict,, drought and famine – not as a gambit for a renewed imperialism (long since discarded) but as a proactive global citizen.

And a British government must show it is not prepared to lose the Union on a vote of 50-plus-one. It must make the required majority higher – say, at 60%. The destruction of a state deserves no less. At the same time, it must find a way to involve the rest of the UK’s citizens in the decision. Secession would mean their state would undergo a major change – in which they should have a voice.

The United Kingdom’s size, history and talents mean it has a good chance to succeed in these large challenges. It will take all of these to secure a Union which can be good for its diverse citizens, and do good in the world.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.