Today, more than half of children worldwide are not reaching minimum levels in reading and maths. It is a global problem, but one which has significant implications for the British taxpayer.

There is a strong argument that this lack of learning for children in low- and middle-income countries is one of the root contributors to inequality, conflict, terrorism, inter-generational poverty, instability and poor health. These have direct consequences for Britain: 50 per cent of the Department for International Development budget is allocated to fragile states and regions in order to improve global security.

According to former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, who now leads the Education Commission, by 2050 the number of lives lost each year because of a failure to provide adequate access to quality education would equal those lost today to HIV and malaria, two of the most deadly global diseases. Brown has called the international education crisis the “civil rights struggle of our time”.

New research reveals that roughly nine in ten people in the UK are unaware of this global education crisis.

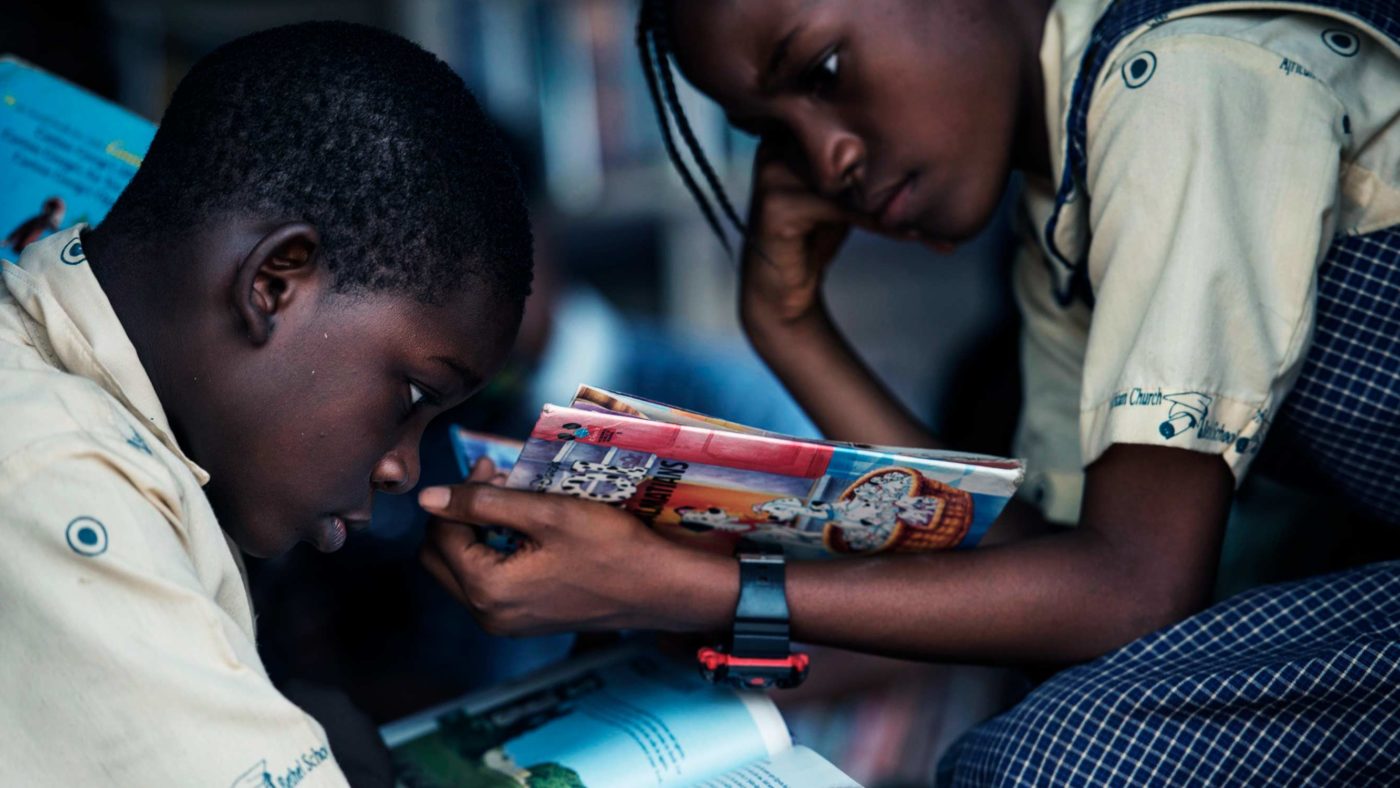

In sub-Saharan Africa, according to official UNESCO statistics, roughly nine in ten school children finish primary school unable to read and write.

However, there are signs of progress. Non-state actors are stepping in to help and the British people seem to approve.

In Africa, one in five children go to a low-fee private school and the number is set to increase to one in four by 2021. Families are choosing this option because it’s affordable and the schools are nearly always better when it comes to learning outcomes for children. The social enterprise I work for runs schools like this, as well as working to improve free government schools.

Some politicians ask: can such a transition towards non-state education be socially acceptable? Even if it works better for children’s learning, can people stomach non-state and private sector actors helping to improve government schools in Asia and Africa?

In fact, over half of the UK public think there should be more private providers of affordable or free education in countries where the government struggles to offer enough education for all. At the same time, more than half the UK public support the use of public-private partnerships in countries where governments are struggling to deliver high-quality education. Almost six in ten people in the UK support social enterprises helping governments who ask for support to improve the teaching quality in their free state schools.

A small, vocal minority would have us believe such public-private partnerships run counter to the principles of a thriving civil society. In fact the opposite is true.

This is a view that is becoming more widely held in the funding community. The World Bank Group have continued to speak out in favour of private sector engagement, following their first ever education report detailing their support for public-private partnerships. The Bank’s education team have been particularly engaged in a potentially transformative public-private partnership in the Nigerian state of Edo. The views of the British public match those of the UK Department for International Development, as its education strategy advocates the use of non-state actors to improve education in developing countries.

Public education system transformation is desperately needed and with many governments constrained by limited budgets and capacity issues, non-governmental organisations can help bridge the gap.

The British public support a similar approach to teacher training too — 58 per cent agreed with the idea of Bridge International Academies supporting teachers in low- and middle-income countries to help improve outcomes for children.

It’s very encouraging to see that many British people support additional education public-private partnerships to help governments in countries that are struggling to offer quality education for all children. The education crisis has global consequences and it’s only when the public and policymakers are aligned that we will see meaningful change.

Bolstering local governments through the provision of technical support such as in EdoBEST, Nigeria or through full scale school management as in LEAP, Liberia enables public education systems to benefit from innovative and cutting edge approaches to teaching.

The education challenge facing developing countries is certainly daunting, but with the support of the public both at home and abroad, their chances of success are all the greater.