The most important policy of Boris Johnson’s new government may be one that wasn’t in the manifesto at all. Today’s news that the government intends radical planning reform is welcome to everyone who understands the profound damage to wages, growth and fairness caused by our decades-long failure to build enough homes in the right places.

I apologize to those rendered catatonic by my endless ranting about it. Luckily someone was listening.

On Tuesday night Dominic Cummings briefed all ministerial aides on the Government’s plans, and “made the point that every time a review is done, planning always comes up as a big drag on productivity, but nobody ever does anything about it. But we are going to do something about it.”

There will be new homes on greenbelt land where there is already development, ‘such as around railway stations’, as Professor Paul Cheshire has been proposing for decades. And ‘Housing Secretary Robert Jenrick and Chancellor Sajid Javid have been quietly preparing a major overhaul of the system’ that will give homeowners and developers the right to add two floors without necessarily needing to apply for planning permission.

It is clever to play to the new Conservative voters in the many northern places that have been building vastly more housing per head than London, by saying it is time for the South East to take some of the load.

There will be a new guarantee that planning ‘applicants will get their fees repaid in full if local authorities don’t meet tight deadlines’, and a new permitted development right to demolish commercial properties and replace it with homes.

Apparently much of this was pushed by Mr Javid as Communities Secretary but blocked by Mrs May.

Much of this is good news, but there are three big questions.

First, design. Will there be a rash of windowless concrete boxes stuck on Victorian mansion blocks, or will parishes, neighbourhood forums and councils be able to set design codes that, without restricting the size of new buildings, will ensure beautiful and sympathetic façades? Will it apply in conservation areas, or will we see a rush of new applications for conservation area designation from people keen to keep the status quo?

Second, what about suburbs? Many suburban front and side gardens have been paved over for parking. You cannot get from 1930s semi-detached houses to beautiful terraces or mansion blocks just by building up. You have to be able to cover the concrete parking spaces with housing – including garages underneath or behind, if the locals wish – with more greenery to match. Otherwise you end up with endless acres of taller semi-detached houses. In London most family homes are occupied by unrelated people sharing. We could do much better.

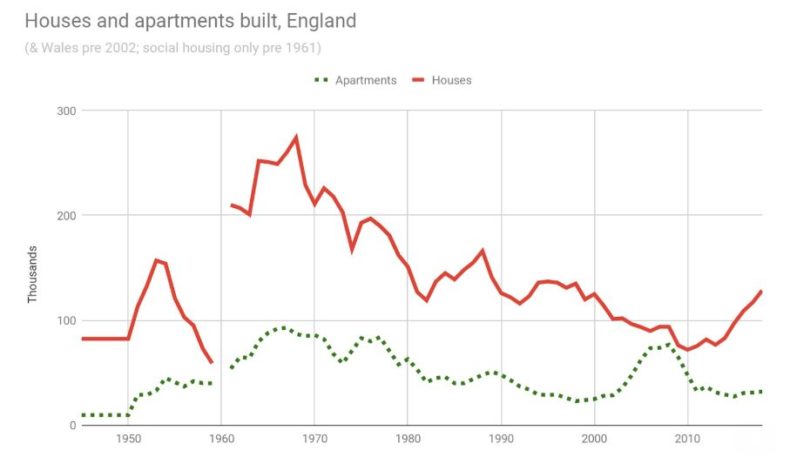

Since the 1947 planning system was introduced, we have never had a mechanism to allow graceful intensification at the scale needed to generate more much-loved places like Hampstead, Soho or Edinburgh’s historic centre. That takes flats, not houses, and we have never built more than 100,000 of those per year – less than one third of what we need if you really want to fix the problem.

Turning suburban semis into taller suburban semis will not make much of a dent in that. You might conceivably double the amount of housing – but you could get five times more housing on a typical semi-detached plot with a more ambitious and popular reform, where residents on a single street can choose a design code and vote for permission for terraced houses or mansion blocks. That would double or treble the value for the original homeowner. We should try that too.

Third, is this sustainable? How popular will it be, and will the next government sweep to power on a NIMBY tide by promising to stop the carnage?

No other sector of the economy depends on strangers allowing government to take away what they see as their entitlements – to light, or to the character of the place where they live. Every other part of property law works by negotiation. But planning was conceived as top-down from the start, supplanting older systems of covenants, leaseholds and rights to light which allowed bargaining to find win-win outcomes.

The current planning system prevents people negotiating to allow more development on terms and with benefits that suit them. In the jargon, planning protections are ‘inalienable’. If other property rights were inalienable, the economy would grind to a halt. We might try to overcome the resulting political opposition by compensating those affected by development, but we don’t even do that.

Ultimately, the only way to a system that doesn’t create blockage, misery and economic harm for another fifty or seventy years is to find ways to allow win-win outcomes, so that some of the enormous profits from development can be shared with local communities.

That system must require some of those profits to be deployed into better design. Good design need not be expensive. The easiest way to get it is to give local people the power to demand it.

An ambitious politician can add more housing. But it takes a truly visionary politician to radically fix the system so it will work well forever, adding plentiful homes while improving the places where we live, so that present and future generations will be grateful.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.