Even by today’s standards of rapid geopolitical change it has been a fast moving few weeks.

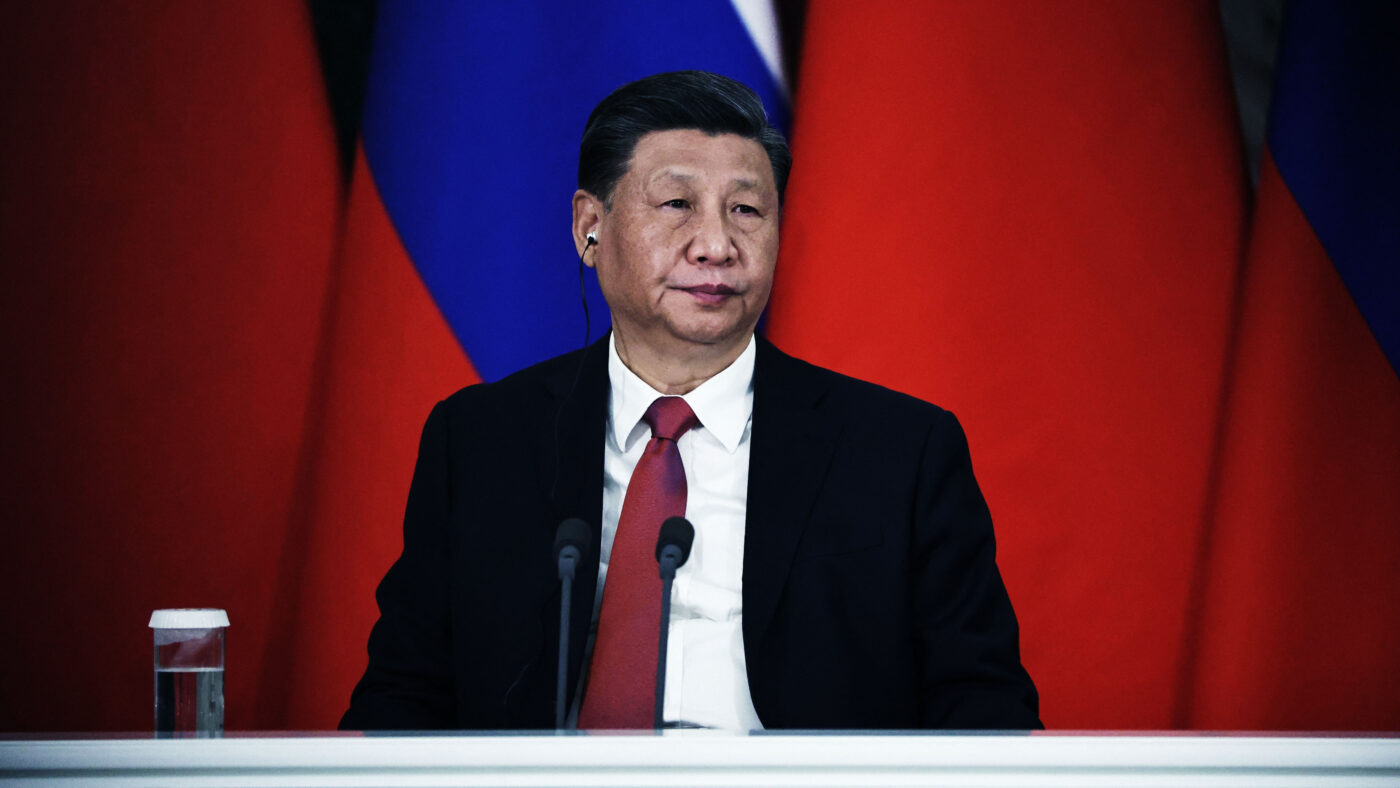

On March 7, China’s new foreign minister, Qin Gang, warned that ‘confrontation and conflict’ are inevitable unless the US stopped trying to ‘contain’ and ‘suppress’ his country. This threat was followed by President Xi flying to Moscow, where he and President Putin reasserted their push towards a multipolar world, away from American hegemony. ‘Right now there are changes – the likes of which we haven’t seen for 100 years – and we are the ones driving these changes together,’ Xi told Putin.

The further alignment of Russia and China on one side was met by the tightening of bonds between two of America’s allies in Asia. At exactly the same time as Xi’s trip to Moscow, the Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida flew to Ukraine, in what has been seen as a veiled message to Beijing that Japan will support Taiwan if any attempt is made at forced reunification. Kishida’s trip came hot on the heels of a Japan-South Korea summit, where the two nations pledged better political and military ties living in the shadow of their giant neighbour.

Amidst this geopolitical maelstrom, and the continued entrenchment of Cold War 2, we also saw the UK’s Integrated Review Refresh (IRR) – an attempt to reset British defence, development, and foreign policies after all the changes of the last two years.

Given the US-UK relationship and the anti-China rhetoric that has become quite common in Britain these last few years, it was a surprise to some that the IRR didn’t take a stronger line on Beijing. Indeed, the messaging was mixed. The country was labelled ‘an epoch-defining challenge to the type of international order we want to see’, but at the same time there were calls for the UK to ‘engage directly with China bilaterally and in international fora so that we leave room for open, constructive and predictable relations’. If Washington and Tokyo believe Beijing to be a major threat and act accordingly, why doesn’t London appear to feel quite so strongly?

The truth is that the UK is too economically exposed to Chinese influence to be able to assertively push back.

On the surface, China is an important but not irreplaceable trade partner, ranking sixth (2021) in Britain’s export markets (just ahead of Switzerland and Belgium) and third in terms of imports. But dig a little deeper and the degree of economic dependence becomes worryingly clear.

A number of leading British companies have heavy exposure to the PRC. One prominent example is HSBC, where 45% of the bank’s 2022 profit before tax came from China and Hong Kong. UK conglomerates Swire and Jardine Mathesons – both important to Britain’s commercial presence in Asia – are not only reliant on the PRC, but show no sign of divesting from China. (Indeed, last year Swire sold off a subsidiary to a US company in order to raise funds ‘to focus on core businesses that have strong growth opportunities in greater China’, according to the company’s Chairman.)

Education has a particular problem. In the academic year 2021/22, 151,690 students studying in the UK came from China, more than all students from the EU combined (120,140). Many universities have become magnets for Chinese students to the extent that their numbers eclipse even those from parts of the UK; Cambridge, for instance, hosted more students in 2021/22 from the PRC (1,525) than from Northern Ireland (175), Wales (350), and Scotland (295) combined.

Rare earth metals are another lever that China has over the UK. These 17 metals are intensively used in everything from wind turbines to mobile phones. Britain’s defence is also reliant on them: each F35 fighter contains more than 400kg of rare earths. The problem is that they are incredibly difficult and ecologically damaging to process. Today, 85% of rare earths are processed by China, a level of control far greater than OPEC has ever wielded over the oil industry.

The bottom line is that China has created economic influence over the UK to such a degree that it could inflict significant pain if it chose to do so. Stopping students coming to Britain would wreak havoc on an education sector already under financial strain; a prolonged disruption to rare earth supplies would likely challenge the defence readiness of our armed forces and seriously disrupt the renewable energy industry.

The UK is far from alone in these vulnerabilities. On the surface, the US suffers many of the same dependencies on China that Britain does. The PRC is America’s third largest trade partner, but again the detail is in the specific dependencies. Even though it has its own rare earths mines, almost all of them are processed in China, and there is little capacity elsewhere in the world to provide an alternative. A significant proportion of America’s microchips come from Taiwan, which could be cut off by China through a blockade or an invasion of the island.

The difference between the US and UK, however, is that Washington is taking active and rapid steps to reduce its exposure to its superpower competitor. The CHIPS act of last year is a $280bn initiative to re-establish a home-grown semiconductor industry, and the Pentagon is funding research to provide alternatives to Chinese rare earths in many sectors.

The UK has no real contingency plans for what to do if relations with China were to break down. However, the IRR does represent a step in the right direction, and the sooner its recommendations (such as doubling China expertise in government) are implemented the better.

The clock is ticking though, with voices in both America and China predicting that the Taiwan question might flare up some time before 2027. As relations between China and America continue to slide, far more preparation is needed to ensure that the UK is ready economically for what could be the biggest, and most damaging, geopolitical shock this century.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.