“Geography is the most fundamental factor in foreign policy because it is the most permanent.”

-Nicholas J. Spykman, The Geography of the Peace, 1944

A forgotten genius

One of the great glories of my job as a political risk analyst is to bring great intellectual treasures that have lain submerged for far too long to the fore. The perennially underrated geostrategic theorist, Nicholas J Spykman, is one such treasure.

To read Spykman today is to find that rarest of things: a foreign policy theory bolstered and derived from real events of the past, even as they make sense of the present and light the way into the future. In our age of hyperbole, plaudits are thrown around with abandon; but it is not too much to say that Spykman is a genius who should be read far and wide if we are to make sense of our world.

Nicholas John Spykman was born in Amsterdam in 1893. In his twenties, from 1913-1920, he bounced around as a journalist accompanying Dutch diplomatic missions to Egypt and Indonesia. But it was in coming to the United States in 1920 that Spykman found his intellectual calling, earning a PhD from Berkeley in 1923. Heading east, Spykman rose quickly in foreign affairs circles, becoming Chairman of the International Relations Department of Yale in 1935, at the remarkably precocious age of 42.

However, just as his career was flowering and he was acquiring international notice for his geostrategic theories, Spykman was struck down by cancer, dying all too soon in 1943. His last and unquestionably most important book, The Geography of the Peace, was published posthumously in 1944.

Building on the work of the British thinker Halford Mackinder, Spykman agreed that the Eurasian supercontinent was the key to dominating the world; powers off this ‘world island,’ such as Imperial Britain and the US, must base their geo-strategy on never allowing any other great power to dominate either half of Eurasia, as to do so was to control the vast proportion of demographic, economic and strategic resources of the world.

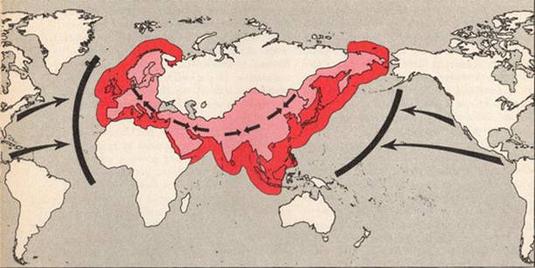

But whereas Mackinder had stressed the centrality of ‘The Heartland’ of Eurasia – the steppes of Russia and the super-continent’s vast interior – Spykman argued instead that it is ‘The Rimland’ of Eurasia that is strategically essential. Spykman geographically defined the rimland geographically as the Western European coastal powers (such as Germany, France and Italy), southern Asia, East Asian littoral countries, China, Japan, as well as southeast Asia. This coastal rimland essentially contains Mackinder’s Heartland (see image below). As he put it succinctly in The Geography of the Peace, “who controls the rimland rules Eurasia, who rules Eurasia controls the destinies of the world.”

Spykman focused on the rimland because it is far richer in resources than the Heartland, and amounts to the connectors of the world’s primary trading routes, while the Eurasian interior remains relatively isolated. Peering out from his World War II perch, and (unlike Mackinder) with history on his side, Spykman correctly noted that all of the world’s recent aspirants for global hegemony (Napoleonic France, Wilhelmine and Nazi Germany, plus Imperial Japan) were rimland powers.

For all these reasons, an America in the process of taking over the global lead from Britain—and geographically located in the same position as an outlier of the Eurasian landmass—must safeguard the rimland above all else. For Spykman, this meant that the US must establish a forward strategic presence in both the European and Asian sectors of the rimland, allowing it to throw back any efforts to dominate either sphere.

Why Spykman speaks to today

As good as Spykman’s geostrategic assessments were in his lifetime, his acumen—like a fine wine—has only grown richer and fuller with the passage of time. As such, adapting Spykman’s thinking to the geopolitics of today pays rich and immediate intellectual and policy rewards.

For even from far away 1944, Spykman (like Napoleon) predicted the rise of China, an alarming turn of events given that it is situated directly in the Asian rimland itself. First, Spykman urged the establishment of US forward basing in both the European and Asian portions of the rimland, a policy position that is even more relevant today, as the lost art of alliance management—following the nadir of the confused Trump years—becomes of paramount importance.

Spykman’s rimland theory ought to remind the US why NATO remains of central importance, along with the growing centrality of the Quad (composed of rimland states India and Japan plus Australia) in Asia. For NATO, the Quad, and stronger ties with vital rimland allies such as Japan remain the best way of American hard power deterring overt strategic rimland challenges in either Europe or Asia. As Spykman knew 75 years ago, rimland alliances amount to America’s best hope for the future.

Second, reading Spykman makes China’s present foreign policy strategy remarkably clear. What is Beijing’s signature Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)–its massive, flagship, Marshall Plan-style Eurasian infrastructure project—but a long-term strategy to economically bind the two rimland sectors in Europe and Asia together under Chinese domination, in a geostrategic effort to dominate the Eurasian world island? The West must recognize that Beijing has read their Spykman, and is acting upon it before it is too late.

Third, the US and its allies must be far tougher regarding Beijing’s build-up in the Asian seas, all on the basis of the spurious ‘Nine-dash line’ which, despite international legal rulings, Beijing claims gives it ownership of 90% of the South China Sea. Beijing knows it cannot dominate the Asian rimland without controlling the waters immediately around it.

Hence, and despite past false reassurances made to President Obama, the regime of Xi Jinping has built artificial islands in the Paracel and Spratly island chains, now equipped with radar systems, fighter jets and anti-submarine aircraft. While re-taking these positions is not feasible, the US should make it crystal clear that no more ‘geographical features’ will be allowed to be built up as military bases while America looks the other way.

Fourth, and finally, to do all this requires a very different sort of American strategic policy than we have seen in the fat, happy, unimaginative years following the end of the Cold War, where the US fleetingly had no immediate strategic rival. Alliance management and diplomacy will be crucial tools to maintain rimland alliances in both Europe and Asia. At the same time, and again in line with Spykman’s timeless thinking, sea power, marine capabilities and air power will be central in this rimland contest for dominance.

For whether we like it or not, China has decided we are fighting a Cold War. That much is now clearly a fact, as some of us have seen for quite a while. The only question is how the West chooses to respond. We could do far worse than thinking along Spykman’s prescient lines.

There is no escaping history

As I worked my way up the ladder in Washington, I was perpetually irritated by the then faddish millennial thinking of both the left (Wilsonians) and the right (neo-conservatives) who somehow thought that history had been done away with in the brief interlude following the immediate end of the Cold War. For if history teaches us anything, it is that it is never over. Other powers were bound to eventually rise and US dominance was bound to be eventually tested. The problem with the Wilsonian and neo-conservative ascendancy is that it has wasted precious time, leaving the US and its allies without an intellectual compass to guide them.

That is where Spykman, grounded in history and empirical facts, comes in. As he so wisely put it, countries cannot escape geography, “however skilled the Foreign Office, and however resourceful the General Staff”. While countries cannot escape reality, Spykman’s precious gift is to give us all a roadmap, successfully making sense of this seemingly baffling new world.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.